- Topics

-

Topics

See our analysis on civil society and how it shapes culture, politics, and policies

Read our insights on the shifting political landscape and what it means for Palestine

Learn more about the policies and practices shaping the Palestinian economy

Strengthen your understanding of the unique conditions for Palestinian refugees across the Middle East

-

- Analysis

-

Analysis

In-depth analysis on existing or potential policies that impact possibilities for Palestinian liberation.

Insights and perspectives on social, political, and economic questions related to Palestine and Palestinians globally.

Concise analysis into a specific policy, its background and implications.

Commentary that brings together insights from multiple analysts.

Compilations of past Al-Shabaka works surrounding a specific theme.

Longer-form, ad hoc projects that seek to confront research questions outside the scope of our regular analysis.

A policy-driven research initiative by Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network.

Our monthly webinar series that brings together Palestinian experts.

Featured

The announcement of the National Committee for the Administration of Gaza (NCAG), a 15-member technocratic body chaired by Ali Shaath, signals a shift toward depoliticized governance in Gaza amid ongoing genocide. Shaath, a Palestinian civil engineer and former deputy minister of planning and international cooperation, will lead an interim governing structure tasked with managing reconstruction and service provision under external oversight. While presented as a neutral technocratic governing structure, the NCAG is more likely to function as a managerial apparatus that stabilizes conditions that enable genocide rather than challenging them. This policy memo argues that technocratic governance in Gaza—particularly under US oversight, given its role as a co-perpetrator in the genocide—should be understood not as a pathway to recovery or sovereignty, but as part of a broader strategy of genocide management. Yara Hawari· Jan 26, 2026This policy brief introduces de-healthification as a framework for understanding Israel’s systematic destruction of Palestinian healthcare infrastructure, particularly in Gaza. Rather than viewing the collapse of Gaza’s health system as a secondary outcome of the genocide, the brief argues that it is the product of long-standing policies of blockade, occupation, and structural neglect intended to render Palestinian life unhealable and perishable. By tracing the historical evolution of de-healthification, this brief argues that naming the process is essential for accountability. Because intent is revealed through patterns of destruction rather than explicit declarations, the framework of de-healthification equips policymakers, legal bodies, and advocates to identify healthcare destruction and denial as a core mechanism of settler-colonial control.

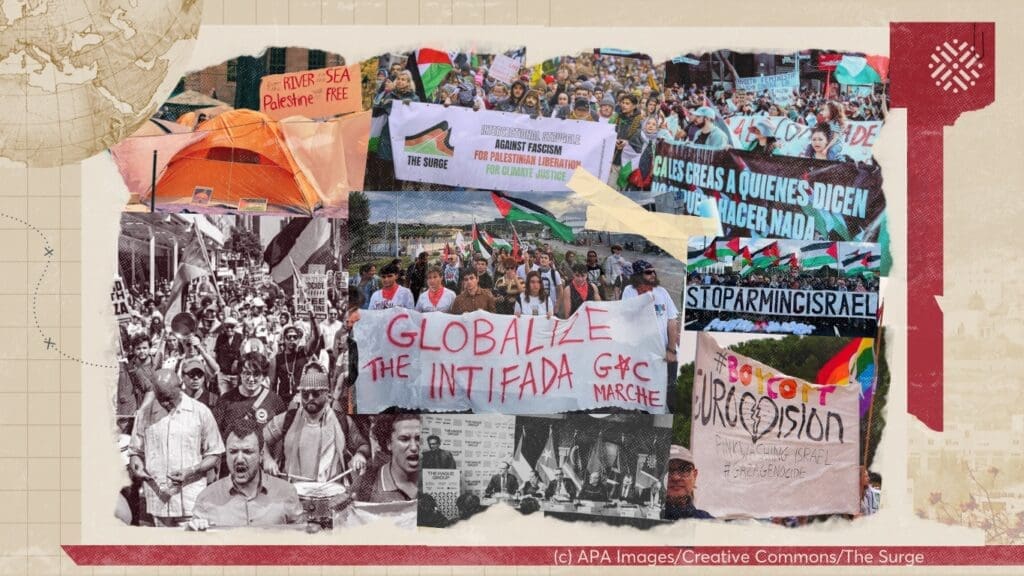

Yara Hawari· Jan 26, 2026This policy brief introduces de-healthification as a framework for understanding Israel’s systematic destruction of Palestinian healthcare infrastructure, particularly in Gaza. Rather than viewing the collapse of Gaza’s health system as a secondary outcome of the genocide, the brief argues that it is the product of long-standing policies of blockade, occupation, and structural neglect intended to render Palestinian life unhealable and perishable. By tracing the historical evolution of de-healthification, this brief argues that naming the process is essential for accountability. Because intent is revealed through patterns of destruction rather than explicit declarations, the framework of de-healthification equips policymakers, legal bodies, and advocates to identify healthcare destruction and denial as a core mechanism of settler-colonial control. Layth Malhis· Jan 11, 2026The global reckoning that followed October 7, 2023, marked a profound rupture in how Palestine is understood worldwide. The Gaza genocide exposed how Israeli mass violence is not exceptional or reactive, but foundational to the Zionist project. What was once framed as a “conflict” to be managed is now widely recognized as a system of domination to be dismantled. It ushered in a shift away from the technocratic language of peace processes and toward an honest confrontation with the structural realities Palestinians have long named: settler colonialism, apartheid, and the ongoing Nakba. The commentary argues that the Israeli genocidal campaign in Gaza has radicalized the world. When crowds march through global capitals demanding a free Palestine, they simultaneously articulate demands for the abolition of racial capitalism, extractive regimes, climate injustice, and all forms of contemporary fascism. In this moment of radical clarity, Palestine becomes a lens through which the underlying architecture of global domination is laid bare—and through which new horizons of collective freedom emerge.

Layth Malhis· Jan 11, 2026The global reckoning that followed October 7, 2023, marked a profound rupture in how Palestine is understood worldwide. The Gaza genocide exposed how Israeli mass violence is not exceptional or reactive, but foundational to the Zionist project. What was once framed as a “conflict” to be managed is now widely recognized as a system of domination to be dismantled. It ushered in a shift away from the technocratic language of peace processes and toward an honest confrontation with the structural realities Palestinians have long named: settler colonialism, apartheid, and the ongoing Nakba. The commentary argues that the Israeli genocidal campaign in Gaza has radicalized the world. When crowds march through global capitals demanding a free Palestine, they simultaneously articulate demands for the abolition of racial capitalism, extractive regimes, climate injustice, and all forms of contemporary fascism. In this moment of radical clarity, Palestine becomes a lens through which the underlying architecture of global domination is laid bare—and through which new horizons of collective freedom emerge. Tareq Baconi· Dec 21, 2025

Tareq Baconi· Dec 21, 2025

-

- Resources

- Media & Outreach

- The Network

Refugees: Israeli Apartheid’s Unseen Dimension

Even among Palestinian activists, discussions about the Israeli crime of apartheid ignore the centrality of the refugee question. One reason for this “oversight” is the fact that the colonial context of apartheid in both South Africa and Palestine is not well understood. Another reason is that for many, not only among the diplomatic community and the United Nations, the division of Palestine into at least two states is perceived as a given, and the Palestinian population of the state-to-be is considered to be the “Palestinian people.” The fact that the PLO leadership has itself adopted this position and transformed itself from a liberation movement into a “Native Authority” similar to those of colonial Africa has encouraged other proponents of partition. They focus on Israeli apartheid practices in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip, occasionally extending their analysis to the part of Palestine conquered in 1948.

What these analyses fail to grasp is that the crime of apartheid applies to a regime in its totality, and not one or other of its particular manifestations, as the 2011 Russell Tribunal on Palestine recently found (see Victor Kattan’s first-hand report). More importantly, forced population transfer, including the denial of refugee return, lies at the core of Israel’s brand of apartheid. I will discuss both of these points below, as well as the differences between Israeli and South African apartheid.

The International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid, which entered into force in 1976, very clearly covers the universal right to return. Article II states that any state that commits “inhuman acts… for the purpose of establishing and maintaining domination by one racial group of persons over any other racial group of persons and systematically oppressing them” is guilty of committing the crime of apartheid. Among these inhuman acts it includes “any legislative measures and other measures calculated to prevent a racial group or groups from participation in the political, social, economic and cultural life of the country and the deliberate creation of conditions preventing the full development of such a group or groups, in particular by denying to members of a racial group or groups basic human rights and freedoms, including… the right to leave and to return to their country.” The article lists other inhuman acts – such as the denial of the rights to nationality, freedom of movement and residence – that also directly affect refugees.

In other words, even if Israel were to end its apartheid practices toward the Palestinians living within the entire mandate territory of Palestine, it would still be committing the crime of apartheid vis-à-vis Palestinian refugees if it continued to deny their right to return.

A case can easily be made against Israel based on its own laws, policies, and practices. The over 700,000 refugees created in 1947-48 were forcibly prevented from returning. As the then defense minister Moshe Dayan wrote in his memoirs: “We shoot at those from among the 200,000 hungry [Palestinian] Arabs who cross the line [to graze their flocks] – will this stand up to moral review? Arabs cross to collect the grain that they left in the abandoned villages and we set mines for them and they go back without an arm or a leg… [It may be that this] cannot pass review, but I know of no other method of guarding the borders.” 1

In 1952, Israel passed its Citizenship Law with the clear intention of sealing the refugees’ fate. Article 3 states that to be entitled to citizenship, a person would have had to be present “in Israel, or in an area which became Israeli territory after the establishment of the State, from the day of the establishment of the State [May 1948] to the day of the coming into force of this Law [April 1952].” It is worth recalling that two years earlier, the Israeli parliament had passed the Law of Return entitling all Jews, and only Jews, the right to enter and become citizens of the new state.

Similar measures were taken in the wake of the 1967 war, in which Israel displaced over 400,000 Palestinians who were forced into exile. Just after the end of the war, Israeli military authorities carried out a census of Palestinians in the occupied territories; those not registered in that census were not allowed residency status and their right to return was thereby denied. The 90,000 Palestinians who were abroad at the time of the occupation were also stripped of their residency status. Furthermore, Palestinians who were included in the census lost their residency status if they remained abroad beyond a specified period of time.

In 2001, to ensure that Israeli negotiators remained faithful to the Zionist consensus, the Israeli Knesset passed the Entrenchment of the Negation of the Right to Return Law. Section 2 of this law states that “refugees will not be returned to the territory of the State of Israel save with the approval of the majority of the Knesset Members.” Section 1 of the law defines a refugee as a person who “left the borders of the State of Israel at a time of war and is not a citizen of the State of Israel, including, persons displaced in 1967 and refugees from 1948 or a family member.” As such, even if Israeli political leaders did somehow decide to cease their regime’s violation of international law as it pertained to Palestinian refugees, they would need the permission of a parliamentary majority to do so.

Through these laws and policies, the Israeli regime has effectively denied displaced Palestinians their “right to leave and to return to their country.” In the process, it has also forced many additional Palestinians to leave Palestine in order to keep their families together.

Palestinian refugees who have managed to secure a foreign passport from a country with friendly relations with Israel may be allowed to visit as temporary tourists. The only other option available to displaced Palestinians has been Israel’s family reunification process, a complicated and disheartening procedure. The ability of Palestinian citizens of Israel to seek reunification with spouses residing in the occupied territory was stopped in 2002 and then banned by the Citizenship and Entry to Israel Act of 2003, which has been renewed every year since. As for Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, Israel abruptly suspended the family reunification process altogether in 2000, forcing around 120,000 Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip to choose between breaking up their family or going into exile. In 2007, Israel issued around four thousand such visas after an active media campaign by those denied the right to live on their land, and since then it has used these permits as one of the many tools at its disposal to reward or punish the Palestinian Authority.

In short, Israel is clearly denying Palestinians their right to return to their country in law, policy and practice, and is doing so with the intent of illegally maintaining both a Jewish demographic majority and exclusive Jewish control over expropriated Palestinian lands. In other words, Israel has denied Palestinians’ right to return in order to establish and maintain a regime of domination by one group over another, i.e. the crime of apartheid.

There are real, and instructive, comparisons to be made with South African apartheid as regards refugees. South Africa’s large-scale forced population transfer was mostly carried out within the country. The apartheid regime’s Homeland policy sought to concentrate the indigenous Black South Africans, who accounted for 90 percent of the population, within the Bantustans, non-contiguous strips of land constituting 13 percent of South Africa’s land mass. The regime believed that if all the Blacks were internationally recognized as being citizens of other states (the Homelands) then South African apartheid would appear democratic. Over 2.5 million Black South Africans were thus displaced into the Homelands and prohibited from returning to the white areas that supposedly constituted another country.

Another central feature of South Africa’s apartheid regime was that it denied not the right of return, but the corollary “right to leave one’s country.” Black South Africans were required to obtain an exit visa to leave the country, and applications for these were systematically denied as were applications for travel documents that would enable their carriers to travel. The regime, in many cases rightly, feared that these travelers’ destinations were the training camps of the armed anti-apartheid resistance.

To understand this difference we need to conceptualize apartheid as a means and not an end. The goals of South African and Israeli apartheid, although both committed in the context of settler-colonial projects, are radically different. In the case of South Africa, the apartheid regime’s main purpose was to exploit the black workers in the country’s mines, factories and households. The expulsion of a black person in this context was nonsensical as every black South African that crossed the border represented the loss of a potential exploitable worker. As such, the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa was as much about the right to form effective labor unions, protect workers and reclaim the country’s natural resources for its indigenous inhabitants as it was about the right to vote.

Zionist apartheid in the Palestinian context has been driven by the colonists’ ideological need to clear the land of its indigenous inhabitants and replace them with Jewish settlers. Every Palestinian displaced beyond the borders of the mandate territory of Palestine is thus a success for the apartheid regime, and the successful return of any displaced Palestinian is a threat to the regime in its totality. The policy of forced population transfer, including denial of refugee return, is not simply one aspect of Israeli apartheid; it is the cornerstone of the Israeli colonial-apartheid project as a whole. That is why there can never be an end to Israeli apartheid, let alone a durable peace, without the implementation of the Palestinian refugees’ right to return.

Hazem Jamjoum

Latest Analysis

The NCAG: Gaza’s Technocratic Turn to Genocide Management

De-Healthification: Israel’s Engineered Collapse of Palestinian Life

The World Radicalized by the Gaza Genocide

We’re building a network for liberation.

As the only global Palestinian think tank, we’re working hard to respond to rapid developments affecting Palestinians, while remaining committed to shedding light on issues that may otherwise be overlooked.