- Topics

-

Topics

See our analysis on civil society and how it shapes culture, politics, and policies

Read our insights on the shifting political landscape and what it means for Palestine

Learn more about the policies and practices shaping the Palestinian economy

Strengthen your understanding of the unique conditions for Palestinian refugees across the Middle East

-

- Analysis

-

Analysis

In-depth analysis on existing or potential policies that impact possibilities for Palestinian liberation.

Insights and perspectives on social, political, and economic questions related to Palestine and Palestinians globally.

Concise analysis into a specific policy, its background and implications.

Commentary that brings together insights from multiple analysts.

Compilations of past Al-Shabaka works surrounding a specific theme.

Longer-form, ad hoc projects that seek to confront research questions outside the scope of our regular analysis.

A policy-driven research initiative by Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network.

Our monthly webinar series that brings together Palestinian experts.

Featured

The announcement of the National Committee for the Administration of Gaza (NCAG), a 15-member technocratic body chaired by Ali Shaath, signals a shift toward depoliticized governance in Gaza amid ongoing genocide. Shaath, a Palestinian civil engineer and former deputy minister of planning and international cooperation, will lead an interim governing structure tasked with managing reconstruction and service provision under external oversight. While presented as a neutral technocratic governing structure, the NCAG is more likely to function as a managerial apparatus that stabilizes conditions that enable genocide rather than challenging them. This policy memo argues that technocratic governance in Gaza—particularly under US oversight, given its role as a co-perpetrator in the genocide—should be understood not as a pathway to recovery or sovereignty, but as part of a broader strategy of genocide management. Yara Hawari· Jan 26, 2026This policy brief introduces de-healthification as a framework for understanding Israel’s systematic destruction of Palestinian healthcare infrastructure, particularly in Gaza. Rather than viewing the collapse of Gaza’s health system as a secondary outcome of the genocide, the brief argues that it is the product of long-standing policies of blockade, occupation, and structural neglect intended to render Palestinian life unhealable and perishable. By tracing the historical evolution of de-healthification, this brief argues that naming the process is essential for accountability. Because intent is revealed through patterns of destruction rather than explicit declarations, the framework of de-healthification equips policymakers, legal bodies, and advocates to identify healthcare destruction and denial as a core mechanism of settler-colonial control.

Yara Hawari· Jan 26, 2026This policy brief introduces de-healthification as a framework for understanding Israel’s systematic destruction of Palestinian healthcare infrastructure, particularly in Gaza. Rather than viewing the collapse of Gaza’s health system as a secondary outcome of the genocide, the brief argues that it is the product of long-standing policies of blockade, occupation, and structural neglect intended to render Palestinian life unhealable and perishable. By tracing the historical evolution of de-healthification, this brief argues that naming the process is essential for accountability. Because intent is revealed through patterns of destruction rather than explicit declarations, the framework of de-healthification equips policymakers, legal bodies, and advocates to identify healthcare destruction and denial as a core mechanism of settler-colonial control. Layth Malhis· Jan 11, 2026The global reckoning that followed October 7, 2023, marked a profound rupture in how Palestine is understood worldwide. The Gaza genocide exposed how Israeli mass violence is not exceptional or reactive, but foundational to the Zionist project. What was once framed as a “conflict” to be managed is now widely recognized as a system of domination to be dismantled. It ushered in a shift away from the technocratic language of peace processes and toward an honest confrontation with the structural realities Palestinians have long named: settler colonialism, apartheid, and the ongoing Nakba. The commentary argues that the Israeli genocidal campaign in Gaza has radicalized the world. When crowds march through global capitals demanding a free Palestine, they simultaneously articulate demands for the abolition of racial capitalism, extractive regimes, climate injustice, and all forms of contemporary fascism. In this moment of radical clarity, Palestine becomes a lens through which the underlying architecture of global domination is laid bare—and through which new horizons of collective freedom emerge.

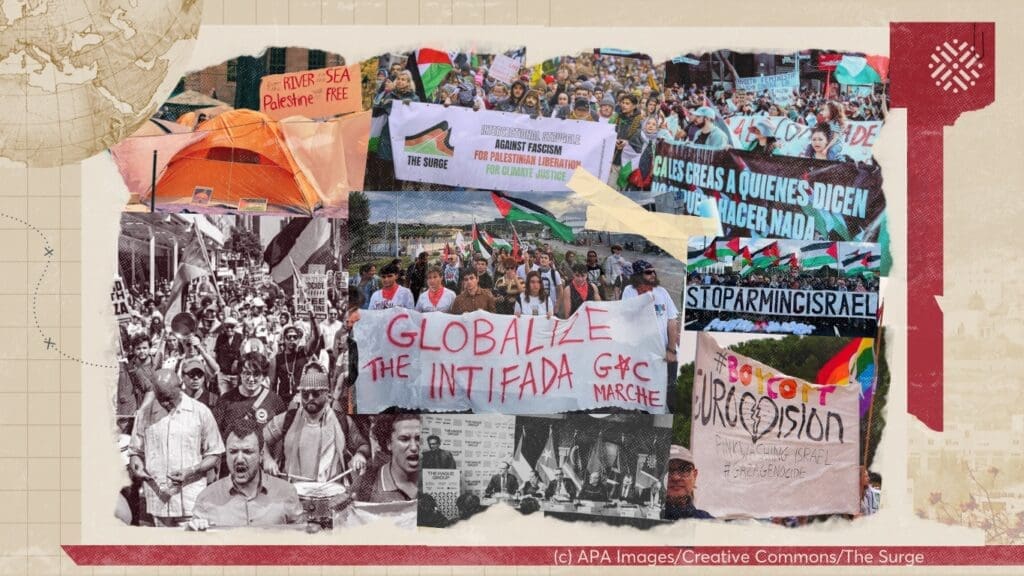

Layth Malhis· Jan 11, 2026The global reckoning that followed October 7, 2023, marked a profound rupture in how Palestine is understood worldwide. The Gaza genocide exposed how Israeli mass violence is not exceptional or reactive, but foundational to the Zionist project. What was once framed as a “conflict” to be managed is now widely recognized as a system of domination to be dismantled. It ushered in a shift away from the technocratic language of peace processes and toward an honest confrontation with the structural realities Palestinians have long named: settler colonialism, apartheid, and the ongoing Nakba. The commentary argues that the Israeli genocidal campaign in Gaza has radicalized the world. When crowds march through global capitals demanding a free Palestine, they simultaneously articulate demands for the abolition of racial capitalism, extractive regimes, climate injustice, and all forms of contemporary fascism. In this moment of radical clarity, Palestine becomes a lens through which the underlying architecture of global domination is laid bare—and through which new horizons of collective freedom emerge. Tareq Baconi· Dec 21, 2025

Tareq Baconi· Dec 21, 2025

-

- Resources

- Media & Outreach

- The Network

Palestinians on the Road to Damascus

A Temporary People

One hot summer day in 2011, the residents of the beleaguered Homs neighborhood of Al-Khaldyeh were struggling to identify the bodies of two men. There was something unusual about the bodies even by the now morbidly gory Syrian standards. They were merely skeletons with worn-out fatigues, and a few personal belongings. The unearthing of their bodies was collateral damage to a stray bomb. They had been blown out of their unmarked shallow makeshift grave by the shells of the Syrian army against the rebellious neighborhood. The residents decided the belongings were clearly from the 1980s, the military fatigues were Palestinian. The story of Syrian Palestinians – like that of most Syrians – is one of many tucked-away skeletons that are thrown into the open, unannounced yet badly needing to be addressed.1

Syria is home to some half a million Palestinian refugees, the great majority of whom were born into a dictatorship that oppresses them and its own people in the name of Arab unity and steadfastness in the face of Zionism and imperialism. Their imagined and lived geographies could not be farther apart. They know the streets of Homs, Aleppo, Deraa, and Damascus like the palms of their hands. Their schools, named after their villages and towns in Palestine, hoist the flag of the United Nations.

Like their Syrian brethren, once in tenth grade, they could be automatically enrolled in the Baath party. Their ID cards are identical to those of Syrians, with the only difference being the red words “temporary residence” on top. Their travel documents could be taken for a Syrian passport, were they not one shade of blue lighter – and the misspelled “Travel Document for Palestinian Refugies” on the cover. Many Syrian Palestinians live their temporary lives in shantytowns that are still called “camps.” They follow the news of Jenin and Gaza as if it were their own. They have never been allowed to set foot in either. They religiously commemorate the dates of Palestinian massacres, victories and defeats. They are also obligated to hold rallies saluting the Syrian regime and its victories. Most camps have their own resident Palestinian Uncle Tom. They hate that they need his permits to wed, work or travel, but they learnt the Syrian proverb all too quickly, “kiss the hand that slaps you, and pray [secretly] that it get cut.”

De jure, Palestinians are well integrated into the legal system and are treated equally to Syrians. Most of these rights are legacy amendments that predate the Baath regime.

Some date back to 1956 parliamentary amendments; others such as issuing travel documents to Syrian Palestinians are a Nasserite legacy when Syria was in the United Arab Republic with Egypt. To its credit, once in power, the Baath did not reverse them. However, the logic behind the legal status of Palestinians is a paternalistic relic of a time when Arab countries were self-appointed custodians over the fate of the Palestinians. It went thus: unless constantly reminded, Palestinians would forget their land and cause. Therefore, while they have most of the civil rights of fellow Syrians, they cannot vote or hold Syrian passports. Furthermore, they are required to fulfill the military service requirement their fellow Syrians do. They are usually drafted into either the Syria-aligned Palestine Liberation Army or the Syrian Army.

De facto, the Baath discriminates equally against anyone who does not abide by the official narrative. De facto no one has any meaningful rights under an authoritarian regime. One could say that the revolution started because the majority of Syrians felt they were not integrated into the Syrian state.

Dictatorship from the Standpoint of a Palestinian Refugee

Equality in political suffering does not confer social equality amongst the collectivity of sufferers. Syrians discriminate against Palestinians in ways that are not dissimilar to those in which they discriminate against fellow Syrians. Like the rest of eastern Mediterranean, Syria is a country where almost everyone fancies himself or herself a Professor Higgins. In Shaw’s “Pygmalion,” the professor of phonetics “can place any man within six miles.” Syrians can detect the subtlest dialectic nuances; one vowel shorter or longer and you are automatically cast as “other.” To other Palestinians, Syrian Palestinians sound a little Syrian; to Syrians their accents give them away as not quite from here (perhaps with the exception of Deraa province). Not being from here can make a world of difference in a place where having the right connections is a must to navigate the ubiquitous state security apparatus. Not being from here means you can live in a city all your life but can never be “Ibn Balad” or “of the city” nor enjoy any of the closely guarded tacit privileges conferred by such labels.

Half a century of brutal authoritarian rule means lived memory is livid: livid at the crimes of the regime but more at one’s own cowardice and helplessness in the face of the regime. Most Syrians have gone through a ritual of pacification. This means oppression seeps down one micro power stratum at a time. A refugee comes at the bottom. For each integrated Palestinian worker, painter, actor, and party member, there are at least two disenfranchised unemployed school dropouts. For each mixed marriage story with a Syrian, there is a story of elopement or stunted love on account of being “a piece of a Palestinian / a piece of a refugee.” Such problems plague all Syrians. Palestinians cannot escape them and are usually less equipped to maneuver them than their Syrian counterparts by virtue of their out-of-placeness.

Dictatorship erects what Syrians call a “wall of fear.” A virtual wall premised on the brutal retribution of the regime’s Amn or Mukhabarat (security and intelligence services.) There is nothing that is not housed within these walls. The memoirs of one Syrian political prisoner speak of a fellow prisoner who was detained for more than a decade because of a dream he had. Self-preservation necessitates silence. Apathy becomes the modus operandi of the average citizen while ignorance mushrooms on the wall of fear.

Palestinians have to leave UNRWA schools for public schools in the tenth grade. I remember on my first day in my new high school someone asking me “So you go back to Palestine everyday after school?” I laughed and told him “No. We live a five minute walk away.” As it turned out our house was closer to school than his. The naïveté exhibited in this question was not merely a fact of our young age at the time. He was Syrian; I was probably the first Palestinian he had met. In the collective imagination of Baathist Syria, Palestine was rendered theme, a topic and at best a place, dear yet always remote from the lived reality of the majority of Syrians. The ignorance displayed in my friend’s question was not a sign of ignorance of regional politics or that Syrians had a sizable Palestinian community of second and third generation refugees living in their midst. It was rather a symptom of life under dictatorship, namely the hindered knowledge of one’s own neighborhood, one’s own city.

Authoritarian rule meant that most questions were banned; the few that are sanctioned have ready-made state-manufactured/endorsed answers. It meant the highly diverse Syrian society had to become uniform and monotone. The result was a country where almost everything was reduced to a stereotypical caricature. Damascenes to the rest of Syrians were cunning capital dwellers, Homs the city of fools, Hamah to be visited only for its Halawet el Jibn (cheese-based) desert and only Alawites pronounce the “qaf” and drink maté. By extension, Palestinians were faraway victims celebrated daily on state TV and in school curricula.

Today most Syrians are in a state of bewilderment. Like the Homsis of Khaldiyeh, they gaze as they try to make out the identities of the suddenly uncovered. How come they never knew their own country, their towns and villages, or their neighbors, not to mention their Palestinians? They heard of places like Jarjanaz, ‘Amouda and Kafr Anbel for the first time during the last 17 months of revolution. The places they thought they knew have only come alive through YouTube videos relayed on regional news channels.

The culture of ignorance spread by the Baath regime had damaging effects on Syrian society at large. When it came to the relationship with Palestinians, it buried all kinds of real historical affiliations and kinship between Palestinians and Syrians under a heap of official talk of Arab camaraderie that, with the passage of time, rang more and more hollow. Coupled with fear, this culture facilitated rampant distrust amongst the citizenry. Invariably, disenfranchised minority communities such as Kurds and Palestinians suffer the most under such conditions.

Revolutionary Times

A popular term born out of the precarious condition in which Palestinians found themselves during the Syrian revolution is “positive neutrality.” Its oxymoronic implications are not completely new to Palestinians, think Emile Habiby’s “Pessoptimist.” They delineate the paradoxical im/possibility of action available to the Palestinians. On the one hand, Palestinians are de facto Syrian in their lived experiences. They both understand and feel the oppression against which Syrians rose up because they were subjected to it themselves. On the other hand, their formal status as non-citizens and the fate of long-established Palestinian communities in the wake of regional upheavals (Libya 1990, Kuwait 1991, Iraq 2003, Lebanon 1975, 1982, 2006) serve as a concrete reminder of the evanescence of their status. With Israel’s decades-long objection to repatriating these Palestinians to their ancestral Galilean homes, once outside Syria, they are treated as stateless and most countries are wont to deny them entry.

From a purely Palestinian perspective, it could be argued that Palestinians have always had even more reason to rise up against the Assad regime than their Syrian counterparts. The regime oppressed them in the name of Arab unity and defense of their cause. Between the ardently apolitical UNRWA and overwhelmingly authoritarian regime, camps could offer no political refuge for Palestinians. This led to a complete standstill in meaningful political activism inside a community that has a long tradition of organizing and one that faces existential dilemmas daily.

For decades, the Baath regime subverted any radical or militant option available to Palestinians in Syria in the name of awaiting the Godotian right moment. Under the guise of opposing the Oslo agreement, it Syrianized the Palestinian political representation inside Syria and, for the most part, reduced it to a Palestinian carbon-copy of Syria’s own puppet National Progressive Front. Just like the Syrian parliament became a rubberstamp for the diktats of the regime, so was the nature and makeup of the Palestinian factions in Damascus restructured to accommodate the political needs of the regime. The legitimacy of these factions was ultimately derived from their regional strategic benefit to the Baath regime rather than from true local representation of the mood on the streets and alleyways of the camps of Homs, Hama and Deraa. This alliance between the leadership of Palestinian factions in Syria and the Baath regime worked well to keep both in power and circumvent the aspirations of both of their constituencies.

To the Baath regime, Palestinians have generally been one more card it could deal when and how it saw fit. In the early weeks of the uprising the regime scrambled to offer its own competing narrative. The feminist professor-of-literature-turned-presidential-spokesperson, Buthayna Shaaban, instructed reporters in xenophobic fear mongering. She found none other than the tiny impoverished Palestinian community of the coastal city of Latakia to scapegoat as shifty outsiders working to stir violence in the country.

Cornered by the internal pressure from peaceful demonstrators in the early months of the revolution, the regime signaled to one of its crony Palestinian factions inside al-Yarmouk in a step unprecedented in its modern history that it would not stop a march to death towards its borders with occupied Golan. Palestinian refugees flocked in their hundreds on the 63th anniversary of the Nakba and unarmed broke through the border fence. In the predictable fire that followed four Palestinian lives were lost to a media stunt that ultimately did nothing to bolster the image of the crumbling regime. More recently, the regime tried (and largely failed) to recruit Palestinians as shabbiha (state-sponsored thugs) in Homs and Damascus to suppress and intimidate Syrians and fellow Palestinians.

Palestine and Palestinians in the Revolution

Culturally, the Syrian revolution has already won. The vibrancy of the new cartoons, slogans, and skits that have come to life during the revolution demonstrate that the mind has already been liberated from the monolithic mimicking of party-line official talk. A major feature of the cultural production emerging out of the beleaguered Syrian cities, towns and villages has been its inspiration by a long history of Palestinian resistance culture. During the siege of Baba Amr, slogans such as “Baqoon ma baqiya al-za’tar wal zaitoun” (we will stay in place, with the thyme and the olives) or “Haser Hisarak” (besiege your besieger) became part and parcel of the Skype-relayed dispatches of the Revolutionary Council of the City of Homs. Facebook pages of Syrian graphic artists both inside and outside Syria started featuring artwork with popular resistance poetry by Mahmoud Darwish against a backdrop of such photographs as the clock tower of the city of Homs, now a famous symbol of the revolution. Other artwork included modified Naji Al-Ali cartoons that satirize the Baath regime.2 Perhaps one of the many ironies of this revolution is that the Baath regime has finally succeeded in bringing the suffering of Palestinians into Syrian homes; this time in ways more intimate and effective than an official newscast.

On the ground, thousands of Palestinians in various capacities collectively and individually rose up alongside their Syrian brethren against the regime. According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights 150 Palestinians were killed in the last 17 months of the revolution; Zaman Al-Wasl puts the figure at 300.3

In discussing the question of Palestinian participation in the revolution one needs to take into account the conditions of their existence.

Two factors have historically impeded an honest assessment of the conditions of Palestinians in Syria: Lebanon and Al-Yarmouk. Lebanon’s notoriously bad treatment of its Palestinian population can make a shantytown with running water and functioning sewage system look luxurious. Therefore, it is misleading to use the living conditions of Palestinians in Lebanon as a measuring stick for other Palestinian (or any refugee) communities.

At the other end, the entrepreneurial vibrancy of Al-Yarmouk is the exception to the rule of Palestinian presence in Syria. Al-Yarmouk’s narrow, yet relatively prosperous streets, camouflage its many titles: camp, neighborhood, and suburb. They also camouflage its poorer sections and the various identities of its residents. About 150,000 Palestinians live in Al-Yarmouk but they constitute less than half or in some estimates a quarter of its residents. The rest are a collage of Syrians from other parts of Syria or Damascus who found affordable housing or job opportunities on its streets. Its relative proximity and inclusion in the city transport system facilitated a dynamic and ever-changing character. After 2003 the old refugees received new ones from Iraq before they dispersed into farther cheaper housing outside Al-Yarmouk.

The camp managed to remain a safe haven for the most recent batch of refugees from adjacent neighborhoods of At-Tadamon and Al-Hajar Al-Aswad. It has been increasingly pushed to militarization mainly but not exclusively by Ahmad Jibreel, the Damascus-based leader of Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC) and Tareq Al-Khadra the head of the Syria-based Palestine Liberation Army. Around 20 of its residents were killed in mortar bombardment in August 2012. Al-Yarmouk’s hodgepodge social makeup has made it hard for any party to political group to claim it as its own. Its size and political significance will only grow with coming days.

About half the Palestinian population in Syria is concentrated in very densely populated camps roughly half a square kilometer in size. Most of these camps are isolated (Al-Nairab camp lies 15 minutes drive away from Aleppo City proper) and in some cases are even fenced in (the walls of Al-Baath University and its dormitory units sandwich Al-‘Adeen Camp in Homs). This renders Palestinians sitting ducks to the overwhelming firepower of the Syrian army at the slightest sign of sympathy with the revolution as was exemplified by the recent fate of the Deraa refugee camp. Since the first days of the revolution, Palestinians were killed while trying to smuggle food and medical supplies to besieged Syrians in Deraa proper.4 This unwavering support for the revolution earned the Deraa camp the wrath of the Syrian Army. The camp continues to be the target of repeated military incursions (June-August 2012), its residents are detained, tortured and summarily executed; whatever is left of it still stands with the revolution.

When the Syrian army launched an all out campaign on Baba Amr neighborhood in Homs in February 2012, the neighboring Al-‘Adeen camp sheltered hundreds of its terrified impoverished residents running for their lives. The camp’s “Bissan” hospital, the only operating hospital in the city, treated the wounded from Baba Amr. Its doctors and nurses risked their lives to save those coming from Baba Amr and beyond. The Security Services later handed its Palestinian resident shabbeeh a list of more than 100 wanted Palestinians with charges ranging from “carrying weapons” to “treating the wounded.” The small semi-walled camp continues to hang at the edge of a torn city, uncertain whether its walls will prove its survival or its undoing.

The Compass Loses Direction on the Road to Damascus

Syria’s revolution is one of the most divisive issues Palestinians face since the signing of the Oslo accords. Part of the problem lies in the assumption that past revolutionary credit (real or perceived/militant or rhetorical) can lend legitimacy to otherwise indefensible acts. Moreover, a strange mélange of Syrian state media, muted sectarianism and international interests have all worked to render an otherwise just struggle for freedom confusing. Syria presented an unconventional, and inconvenient, foe. On the one hand, some Damascus-based Palestinians have brushed the dust off their old revolutionary compasses and declared Palestine the pole. Anyone who points towards it is a friend; his enemies must also be the enemies of Palestinians. On the other hand, for Ramallah politicians, Syria has offered a rare and cost-free opportunity to score revolutionary points without needing to wipe the dust off their revolutionary guns. The positions of both are grounded in clear immediate and convenient political interests.

The pitfalls of some Palestinian intellectuals outside Syria and mostly within the (intellectual and physical) confines of the Empire have been far more serious if marginal in impact. For such intellectuals, anti-imperialism can easily elide more important and more basic “anti-”s. When they deem the struggle for dignity and freedom in Syria to be of a lesser value than the struggle against Imperialism, they fail to account for more than 60 years of complex history of post-independence Syria. They critique the universalizing aspects of American and European academies, but end up universalizing their number one opponent (the Empire) as everyone else’s. Until revolutionary Syrians do so too, their consciousness is false, their struggle futile, and their blood worthless.

Promises from the Storm

Already Palestinians from Syria are refugees anew in Jordan and Lebanon. Their Syrian travel documents abroad are as valuable as the Syrian pound. . . abroad. Only they cannot be exchanged for local papers. They already wonder how, unlike most things, seniority for a refugee invites more misfortune and maltreatment instead of respect and understanding. They wonder why their fellow Syrian refugees were, at least initially, able to enjoy the freedom of movement in Jordan while they are incarcerated in a dystopian internment camp called of all things “Cyber City.”5 They already ask, “Will the new Syrians remember what it felt like to be a refugee?”

As the Syrian state implodes and as the regime mutates into a super-militia (see the recent report by the International Crisis Group) what awaits Palestinians today is as murky as the fate of Syria itself. They have managed so far to defy the rising tide of sectarian classification and to stand to the extent possible with the revolution. Ultimately, they will no longer be able to maintain a stance of “positive neutrality” and the neutrality will have to become loudly positive. Will it remain positive or will it get Syrianized, sectarianized or weaponized? To a great extent, the answer depends on whether the revolution succeeds in toppling a militia that has its own air force. And if it does how many of its stated ideals will survive the deals it strikes along the way to the palace on Mount Qasyoun?

Ahmad Diab

Latest Analysis

The NCAG: Gaza’s Technocratic Turn to Genocide Management

De-Healthification: Israel’s Engineered Collapse of Palestinian Life

The World Radicalized by the Gaza Genocide

We’re building a network for liberation.

As the only global Palestinian think tank, we’re working hard to respond to rapid developments affecting Palestinians, while remaining committed to shedding light on issues that may otherwise be overlooked.