- Topics

-

Topics

See our analysis on civil society and how it shapes culture, politics, and policies

Read our insights on the shifting political landscape and what it means for Palestine

Learn more about the policies and practices shaping the Palestinian economy

Strengthen your understanding of the unique conditions for Palestinian refugees across the Middle East

-

- Analysis

-

Analysis

In-depth analysis on existing or potential policies that impact possibilities for Palestinian liberation.

Insights and perspectives on social, political, and economic questions related to Palestine and Palestinians globally.

Concise analysis into a specific policy, its background and implications.

Commentary that brings together insights from multiple analysts.

Compilations of past Al-Shabaka works surrounding a specific theme.

Longer-form, ad hoc projects that seek to confront research questions outside the scope of our regular analysis.

A policy-driven research initiative by Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network.

Our monthly webinar series that brings together Palestinian experts.

Featured

The Israeli regime’s ongoing genocide in Gaza has exposed the failure of international legal frameworks to protect civilians, marking an unprecedented breakdown in the protective function of international law. While the Genocide Convention obligates states to prevent and punish genocide, and the Geneva Conventions establish protections for civilians under occupation, these mechanisms have proven powerless without the political will to enforce them. In this context, eight Global South states—South Africa, Malaysia, Namibia, Colombia, Bolivia, Senegal, Honduras, and Cuba—have launched the Hague Group, a coordinated legal and diplomatic initiative aimed at enforcing international law and holding the Israeli regime accountable. This policy memo examines the group’s efforts to challenge entrenched Israeli impunity. It highlights the potential of coordinated state action to hold states accountable for violating international law, despite structural limitations in enforcement. Munir Nuseibah· Jul 8, 2025On Thursday, June 19, 2025, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stood in front of the aftermath of an Iranian strike near Bir al-Saba’ and told journalists: “It really reminds me of the British people during the Blitz. We are going through a Blitz.” The Blitz refers to the sustained bombing campaign carried out by Nazi Germany against the UK, particularly London, between September 1940 and May 1941. With this dramatic comparison, Netanyahu sought to elicit Western sympathy and secure unconditional support for his government’s latest act of military escalation and violation of international law: the unprovoked bombing of Iran. This rhetorical move is far from new; it has become an enduring trope in Israeli political discourse—one that casts Israel as the perennial victim and frames its opponents as modern-day Nazis. Netanyahu has long harbored ambitions of striking Iran with direct US support, but timing has always been central. This moment, then, should not be viewed merely as opportunistic aggression, but as part of a broader, calculated strategy. His actions are shaped by a convergence of unprecedented impunity, shifting regional dynamics, and deepening domestic political fragility. This commentary examines the latest escalation in that context and discusses the broader political forces driving it.

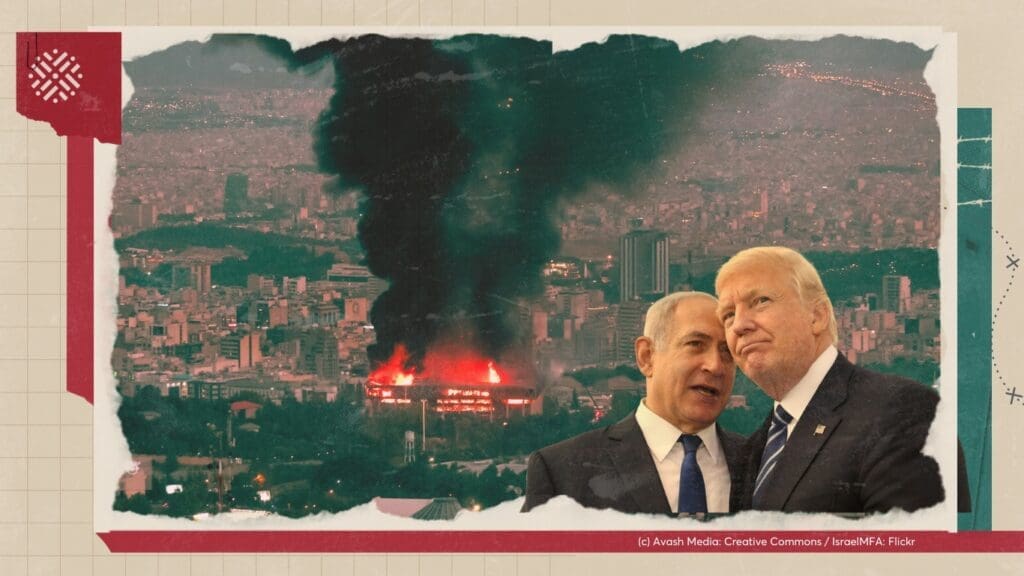

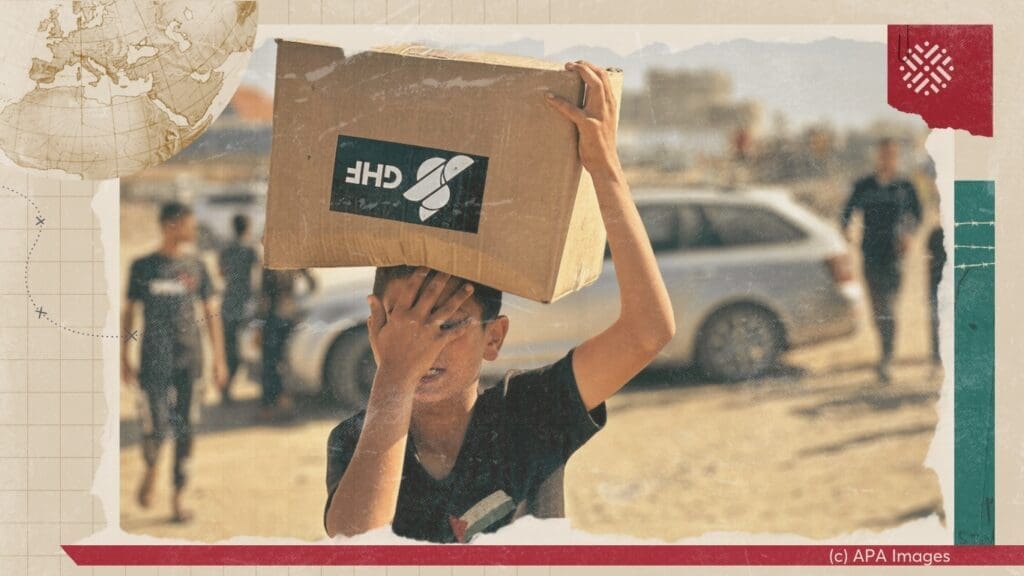

Munir Nuseibah· Jul 8, 2025On Thursday, June 19, 2025, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stood in front of the aftermath of an Iranian strike near Bir al-Saba’ and told journalists: “It really reminds me of the British people during the Blitz. We are going through a Blitz.” The Blitz refers to the sustained bombing campaign carried out by Nazi Germany against the UK, particularly London, between September 1940 and May 1941. With this dramatic comparison, Netanyahu sought to elicit Western sympathy and secure unconditional support for his government’s latest act of military escalation and violation of international law: the unprovoked bombing of Iran. This rhetorical move is far from new; it has become an enduring trope in Israeli political discourse—one that casts Israel as the perennial victim and frames its opponents as modern-day Nazis. Netanyahu has long harbored ambitions of striking Iran with direct US support, but timing has always been central. This moment, then, should not be viewed merely as opportunistic aggression, but as part of a broader, calculated strategy. His actions are shaped by a convergence of unprecedented impunity, shifting regional dynamics, and deepening domestic political fragility. This commentary examines the latest escalation in that context and discusses the broader political forces driving it. Yara Hawari· Jun 26, 2025Launched on May 26, 2025, and secured by US private contractors, the new Israeli-backed aid distribution system in Gaza has resulted in over 100 Palestinian deaths, as civilians navigated dangerous conditions at hubs positioned near military outposts along the Rafah border. These fatalities raise grave concerns about the safety of the aid model and the role of US contractors operating under Israeli oversight. This policy memo argues that the privatization of aid and security in Gaza violates humanitarian norms by turning aid into a tool of control, ethnic cleansing, and colonization. It threatens Palestinian life by conditioning life-saving aid, facilitating forced displacement, and shielding the Israeli regime from legal and moral responsibility. It additionally erodes local and international institutions, especially UNRWA, which has been working in Gaza for decades.

Yara Hawari· Jun 26, 2025Launched on May 26, 2025, and secured by US private contractors, the new Israeli-backed aid distribution system in Gaza has resulted in over 100 Palestinian deaths, as civilians navigated dangerous conditions at hubs positioned near military outposts along the Rafah border. These fatalities raise grave concerns about the safety of the aid model and the role of US contractors operating under Israeli oversight. This policy memo argues that the privatization of aid and security in Gaza violates humanitarian norms by turning aid into a tool of control, ethnic cleansing, and colonization. It threatens Palestinian life by conditioning life-saving aid, facilitating forced displacement, and shielding the Israeli regime from legal and moral responsibility. It additionally erodes local and international institutions, especially UNRWA, which has been working in Gaza for decades. Safa Joudeh· Jun 10, 2025

Safa Joudeh· Jun 10, 2025

-

- Resources

- Media & Outreach

- The Network