About This Episode

Episode Transcript

The transcript below has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

Tareq Baconi 0:00

The question for me today is how do we think about this moment of genocide as a way of resuscitating our revolutionary legacy, of going back into our roots and bringing out a political project, a decolonial project, that’s not about going back to the past because there’s no going back, but it’s rather about how do we think about decolonization and revolutionary politics today, in this day and age, thinking about all of these global challenges. And I think that’s our most urgent task to date.

Yara Hawari 0:39

From Al-Shabaka, the Palestinian Policy Network, I am Yara Hawari, and this is Rethinking Palestine.

Over the last year, Palestine has been irrevocably changed in ways that for many of us were once inconceivable. Since the beginning of the genocide, the Israeli regime has killed over 50,000 Palestinians in Gaza, an estimate provided by the Palestinian Ministry of Health that includes over 6,000 unidentified bodies in the ministry’s possession, and an additional 10,000 assumed to be still buried under the rubble. Devastatingly, some will never be retrieved.

Meanwhile, a July 2024 article in the Lancet medical journal on the importance of accounting for Gaza’s fatalities argued that a conservative estimate of total deaths in conflict scenarios equated to four indirect deaths per one direct death. By this calculation, Israel’s genocide has likely resulted in the loss of over 250,000 Palestinian lives since October 2023.

In addition, Gaza is now home to more than 42 million tons of rubble. These ruins include many people’s destroyed homes, businesses, and essential public infrastructure. Relentless Israeli bombing has also released hundreds of thousands of tons of toxic dust into the air, with long-lasting and deadly consequences.

Eighty percent of schools and universities have been damaged or destroyed. And for the first time since the Nakba, Palestinian children in Gaza did not begin school this year. Concurrently, the Israeli regime and its settler communities stole a record amount of land across the West Bank over the past 12 months.

This theft has been accompanied by increasing violence against Palestinian bodies. Over 700 have been killed, 5,000 injured, and thousands more arrested, bringing the number of Palestinian political prisoners to nearly 10,000. Further north in Lebanon, the Israeli regime expanded its assault and displaced over 1 million people in the space of days and killed over 1,800, including Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah.

Israeli bombardments have continued to target neighborhoods and Palestinian refugee camps from the sky, while colonial forces began a ground invasion in early October 2024.

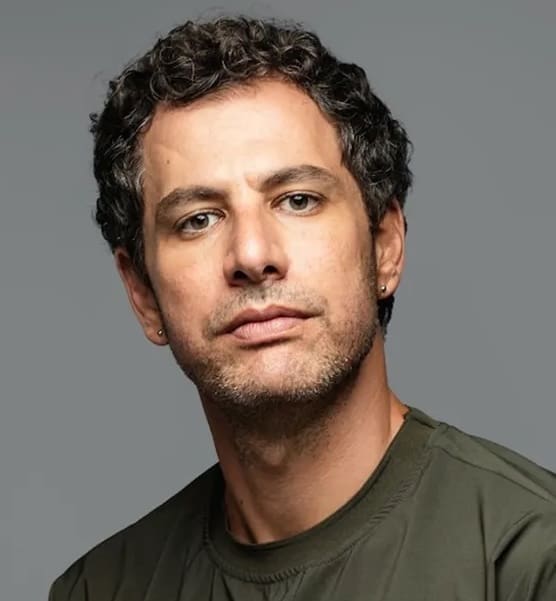

Joining me on this episode is Tareq Baconi, board president of Al-Shabaka. We will be discussing one year on from the start of the genocide in Gaza and the acceleration of the Israeli settler colonial project in the rest of Palestine and beyond. Tareq, thank you for joining me on this episode of Rethinking Palestine.

Tareq Baconi 3:07

Thank you for having me.

Yara Hawari 3:08

Tareq, in this introduction I took stock of the devastating material consequences on the ground and I said that Palestine has been irrevocably changed. What does that mean for you?

Tareq Baconi 3:21

Thank you for this question, Yara. For Palestinians, it’s impossible to go back to October 6th. The genocide is the bloodiest year for Palestinians. We haven’t had this number of Palestinians murdered, including in the Nakba. The devastation that you just outlined at the beginning of the episode is one that will inform everything today.

It will inform our politics, our thinking. It will inform how we wage the struggle. It will inform how we relate to our brothers and sisters in the Gaza Strip and where we go from here. There’s no way for us today to think about what Palestinian liberation is without taking stock of the genocide that is still ongoing.

In many ways that thinking is already taking place and is already evolving, but it will really have to shape our struggle once the ceasefire is achieved and after the killing stops. We’re still very much in the act of witnessing this genocide and attempting to stop it. So in that way, the reality of the past year has irrevocably changed us as Palestinians and as humans, and that will impact our struggle.

But there’s another bigger way in which this past year is unprecedented in how it’s shaped or changed us. And that’s in ways that are not only relevant to Palestine. It’s changed the globe in the sense of showing the limitations of the post-World War II international order, in terms of demonstrating the hypocrisies and the racism of Western liberal democracies — or so-called democracies. And it’s completely shattered the illusion that we’re living in a world of multilateral governance.

It’s highlighted how important it is for us as Palestinians and as allies, as people who are hoping for a more equitable world order, to really engage with some of the issues that have surfaced over the past year — the fact that we can witness a genocide on our phones and not only allow it to happen, but also face narratives that it is self-defense or important, as Western liberal democracies abet it and arm it.

I think it really brings global questions to the fore. And I don’t think there’s a way for us to go back to October 6th, either in a Palestinian context or in a global one.

Yara Hawari 5:54

Tareq, I fully agree. And I want to unpack some of that further. But as you were speaking, you said this has been the bloodiest year for Palestinians, including the year of the Nakba, and every day it does seem that things are more and more horrific than the day before.

A lot of people are asking how on earth is that possible? How is it possible for Israeli soldiers to bomb time and time again hospitals, to force doctors and medical workers at gunpoint to leave their patients, to shoot children in the head, to bomb schools, to destroy every aspect of life in Gaza.

Something that I’ve been thinking about a lot is this idea or this notion that Israel is unstoppable. And I think on the surface it does sometimes feel that way — in the face of this brutality, this cruelty. We have this rogue state violating international law left, right, and center, wreaking havoc across the region.

But I think that statement is untrue and it obscures the responsibility of others, because in reality, it can actually be stopped. There are countries that hold a significant amount of leverage over the Israeli regime. The US and Germany, just to name two — they could literally stop this. Or at least disrupt it.

That’s why I think it’s really important that we don’t fall into that narrative trap, because it also dismisses how we got here. It dismisses and disregards the decades-long impunity that Israel has managed to achieve for itself and has managed to cultivate. And it also dismisses the fact that there are very real mechanisms of accountability that can be used.

Tareq Baconi 7:48

I think that’s absolutely right. I want to say several things in response to this. On the first point, around the insanity of witnessing this level of killing and the disbelief — the sense of suspended indignation — how could they kill at this rate, in this way, without stopping?

I think it’s really important for us to take Zionism out of its exceptional mold. Genocidal regimes in the past have murdered and killed in ways that are horrifying and brutal. And what we’re seeing today is a particularly egregious example of that because we’re witnessing it live on our screens, and the immediacy of it is happening in front of us.

That cracks the illusion that we might have sat in before October 7th — that had we known about these other genocides, maybe the world would have acted to stop them. And now we know that the world wouldn’t have acted to stop them. The reason I’m saying this is because this disbelief that we’re in is also something that we need to sit with and understand. How is Israel able to do what it’s doing?

I think the level of dehumanization has been so pervasive that they may not think they’re killing humans in Gaza. I don’t think they regard Palestinians as human. And I think that is what enables them to continue this level of sadistic violence. There’s no other way to think about some of the images that we’ve seen coming out of Gaza just this week — the bombing of refugee camps, people being burnt alive. There’s a sadism there that I think is driven by a complete internalization of the belief that Palestinians are not humans.

I’m bringing this up because it relates to your point about whether Israel is stoppable or not. Israel is absolutely stoppable. If there’s anything that came out of October 7th, out of Hamas’s attack, it is to shatter this idea that Israel is invincible, that as a military power it can’t be challenged, that as an apartheid regime it can’t be dismantled.

I think we’ve seen — not only through Hamas’s attack, but from the reality that Israel would not have been able to wage this genocide without the US — that Israel is absolutely a settler colony that has always been, and continues to be, dependent on empire, dependent on the foreign metropoles that allow it to do what it is doing. Therefore, in that sense, it is stoppable. There are levers of power that can be used to arrest the kind of atrocities that Israel has been carrying out for a century — not Zionism for a century, Israel since 1948, not just since October 7th.

The reason why it hasn’t been stopped is because this dehumanization of Palestinians isn’t limited to Israel. This is a Western dehumanization. Palestinians are not featuring — and I have to say not just Palestinians, Arabs do not feature — in the thinking of so-called liberal Western states. They believe that Israel is the banner of a civilizational project, that it’s fighting against barbarism. This has always been the underlying assumption of Zionism, and it continues to be, truthfully, one that also informs America’s engagement in the region and America’s engagement specifically with Israel.

This dehumanization is not limited to Israel. It extends far beyond that. And so when we’re thinking about whether Israel is stoppable — of course it’s stoppable. But there’s no will to stop it, because as far as countries like the US are concerned, Israel is serving both their ideological and their strategic purposes. Now, I think that’s completely misplaced, and I do think there’s a divergence of interest, but I don’t think the American administration has opened up to that.

Yara Hawari 11:51

Tareq, I think you’re completely right that the Zionist project and the Israeli regime has completely dehumanized Palestinians. There’s no way they could be doing what they’re doing on such a massive scale and with such support from the Israeli public — some polling showed that like over 95 percent of the Israeli public supports the genocidal actions in Gaza. And I think the only way that’s possible is with such mass dehumanization, which, as you rightly pointed out, extends beyond the Zionist regime. It’s been decades and decades of dehumanization of Palestinians and Arabs by the West and beyond.

As you were speaking, I was thinking in particular about the Western media’s role in this genocide. What we’re seeing and what’s being highlighted over this year is that the groundwork and the foundations for this genocide were laid long ago through this consistent dehumanization. The Western mainstream media has a lot to answer for in this regard. We’ve seen it in the way that they report on the killing of Palestinians, how they consistently unchild Palestinian children, how they completely dismiss and delegitimize Palestinian voices. So I think there is a lot to be reckoned with there.

And something else I want to unpack, which you mentioned briefly, is the role of international law and its place in the Palestinian liberation struggle. In the last two decades, significant segments of Palestine’s civil society and the wider solidarity movement have placed international law at the center of their work — in part because this is a system which claims to uphold certain values, many of which Palestinians also hold dear. Also because of a process of NGO-ization following Oslo, Palestine’s civil society was in many ways forced to break ties with a more revolutionary politics, a more revolutionary discourse, and to adopt international law as the framework for their modus operandi.

And I think, myself included, the ongoing genocide in Gaza has had a profound impact on how the international legal regime is perceived. The Israeli regime has systematically violated the provisions of the Geneva Conventions related to warfare and occupation. The International Court of Justice, the ICJ, one of the highest courts in the world, found the Israeli regime to be committing plausible acts of genocide. Still, not only have the US and UK and others played down these international rulings, they’ve completely disregarded the violations and blocked attempts to hold the Israeli regime accountable through the various legal channels.

I think that many people are inevitably making the comparison between the international response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the international response to the literal genocide in Palestine. I think it’s not only about a lack of implementation and political will, but also about the hegemonic bias which holds certain lives more valuable than others within the international legal regime. I think it speaks to the very foundations of that regime and who it was set up for.

Yara Hawari 13:54

If you’re enjoying this podcast, please visit our website al-shabaka.org, where you will find more Palestinian policy analysis and where you can join our mailing list and donate to support our work.

Tareq Baconi 15:54

We started this episode talking about the fact that after October 7th there’s no going back, that we’ve been irrevocably changed, and I agree with that. We’re living in a moment of rupture, a paradigmatic rupture, where the paradigm we thought we were living in has been fundamentally changed. However, there are continuities.

What you’re talking about, in terms of the limitations of international law, is something that we have been aware of as Palestinians for many years now, if not decades — that this system of international law in its DNA has excused colonialism, has not dealt with indigenous rights or with reparations, has not protected the rights of Palestinian minorities, that this rules-based order is fundamentally colonialist, still, and that we needed to engage with it.

This is Noura Erakat’s work — we need to engage with it politically. We need to be able to deal with international law not as this terrain that is going to give us well-deserved rights, but as something that we will have to struggle for politically. The thinking always was that we engage with international law opportunistically, strategically, in an instrumentalized way. However, after October 7th — and as we see, even before October 7th, after Ukraine — we now understand that this is far more challenging than we might have hoped.

Also, in some ways, we now are living in a world where the mask is off. The emperor has no clothes. There’s no way for Western powers now to talk about legality or rights or justice without many members of the so-called Global South laughing in their face. And this is not only October 7th. This is also Ukraine. This is also the Iraq War. This is also Kosovo. This has a long history of the West co-opting international legal norms and using them in the service of their own hegemonic power.

Now, in Israel’s case specifically, we also have to be aware that Israel systematically created legal precedents over the years in order to be able to do what it is doing today. Extrajudicial executions of Palestinians are illegal under international law. Now the media and most people think of them as targeted assassinations — and that framing paved the way for the Obama administration to carry out extrajudicial executions of Afghans at a rate that was unprecedented. So the kind of erosion of international norms that has been allowed to happen by Israel and by the West is leading us to a world where bombing pagers and phones in civilian areas indiscriminately is something that’s celebrated as a security operation.

This doesn’t come out of a vacuum. This is the premeditated, systematic erosion of rights and of legality and of the international norms that govern the world.

Now, in Israel’s case specifically, Israel today is a rogue state. It’s a pariah state that’s carrying out a genocide actively. It’s documenting the genocide. It’s being proud about it, and it’s spilling it to other countries — to Lebanon and elsewhere in the region. Can you explain to me what international governance will look like after this genocide? What is to stop other rogue states from doing the same? What are the measures that we have to protect vulnerable populations and people against genocide, against this kind of impunity, against the sustainability of apartheid regimes?

I think this is something that is really pressing and urgent for us to grapple with — again, not only for Palestine but on a global stage. And I think in this sense, Palestine becomes the path through which we need to think about decolonizing international law and revising this rules-based order that has only served the powerful.

Yara Hawari 20:25

So you mentioned indigenous rights and sovereignty, and I think this is a really good lens through which to critically examine international law and its biases — not only towards the nation state, but also towards colonial ones.

In 2007, the UN adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the UNDRIP. Unfortunate name, but there we have it. And some people celebrated this. Importantly, it faced huge criticism from indigenous communities themselves, who felt that it not only had a very limited description of indigenous peoples, but also because it didn’t make space for indigenous sovereignty. The declaration stated that nothing in the declaration could be interpreted as encouraging any action that would dismember or impair the territorial integrity or political unity of sovereign and independent states. Reading that, you can see how this is actually actively against the idea of decolonization and indigenous sovereignty.

So I think that’s just one example which shows the inherent flaws in international law, the inherent biases towards settler colonial entities and nation states.

And I think you also mentioned something really important in that intervention — the reorientation towards the Global South. I’m apprehensive to call it this, but we all know that South Africa brought a genocide case against the Israeli regime at the ICJ, the International Court of Justice, and perhaps lesser known is the fact that Namibia extended the legal battle and brought legal action against Germany for facilitating the genocide.

Even with the aforementioned skepticism on the international law front, I do think that these moves were symbolically significant at least. I think it did signal a challenge to Western hegemony and reinforce the notion of Global South solidarity. And I think it’s something we have to think about and take action on in a very intentional and serious way, whilst also maintaining a healthy dose of skepticism.

I think it does require a shifting of energies and efforts — moving away from prioritizing solidarity efforts with people in positions of supremacist power and moving instead towards collective power building with other colonized and marginalized communities.

So all of this is to say that there are significant moves, at least symbolically significant moves, being made within these spaces that are inherently problematic, and some might even argue inherently set up to limit people of the Global South and people under settler colonial domination. But there are also other avenues with these actors that we can pursue, and perhaps other avenues in which we should spend more time and energy.

Tareq Baconi 24:06

I agree with that. When we think about the Global South, we mustn’t think of it as a monolith — because obviously, we weren’t, and arguably even back in the time of the Non-Aligned Movement, there were huge divergences and diversity within that movement.

The Global South today is not a monolith. And I think engagement with it has to be thoughtful and strategic. The way that South Africa is dealing with Palestine looks very different than the way India is dealing with Palestine, and is very different from how Brazil is dealing with Palestine. Each of these states obviously comes with its own baggage, its own strategic priorities, and its own decision-making. So I think the way we engage with countries in the Global South has to be thoughtful.

At the same time, there is somewhat of a shared agenda in the sense that I think not only members of the Global South, but globally, we are interested in having a world order that is able to deal with the global crises we’re facing — for example, climate justice and climate change. So we need to be able to engage in real conversations around what it means for us to move beyond the idea of Western hegemony, beyond the idea of American unipolarity, and towards multilateral governance.

Those questions are at the forefront of most global powers, even if they are not necessarily aligned with the question of Palestine. But this global question is one that we should all be actively engaged in. What’s happening is that Western powers don’t quite understand that this realignment is taking place, and they don’t quite understand that America’s role as the world’s policeman is no longer tenable. Arguably, it never was — obviously, it was an empire that was destructive — but this self-understanding of America’s role as the world’s policeman is not the world we’re in anymore.

And I think the West hasn’t quite understood not only what you call the rise of the Global South, but also that their own empire and America’s desire for Western hegemony and unipolarity is the source of destabilization and destruction in many parts of the world.

I think we’re in the midst of that realignment. As I said, Palestine is central to that. But to your point about how we engage with these questions in international law — I think fundamentally the biggest challenge Palestinians are facing today is that we are not yet at a place where we’re able to engage with all of these questions strategically and politically.

I think the Palestinian movement is immense today. It’s bigger than it has been for a long time. And I think we now have global support and grassroots power and allies and solidarities in ways that would have been unimaginable this time last year. At the same time, I think that we need to be more strategic in terms of how we push this popular power forward. How do we develop political power? How are we able to engage with questions of international law, with foreign policy towards Global South actors, with questions of global governance?

These are strategic questions, and not coincidentally, by design, our leadership — our revolutionary leadership of the past, of the sixties and seventies — has been co-opted and emptied of content and imprisoned and exiled and executed. We need to rebuild that. We’re coming out of three, four decades of the narrowing out of our revolutionary potential as Palestinians, our institutional power to carry out a decolonial agenda. And we need to rebuild that. It’s urgent that we rebuild that, because in the absence of that, I think foreign interests and certainly Western hegemony will try to reassert a paradigm that certainly does not center Palestinians or Palestinian rights.

The question for me today is how do we think about this moment post-October 7th, this moment of genocide? How do we think about it as a way of resuscitating our revolutionary legacy, of going back into our roots and bringing out a political project, a decolonial project, that’s not about going back to the past because there’s no going back, but it’s rather about how do we think about decolonization and revolutionary politics today, in this day and age, thinking about all of these global challenges.

And I think that’s our most urgent task today.

Yara Hawari 28:57

Tareq, I agree with you that thinking and unpacking what decolonization means for Palestinians is perhaps our most urgent task. I want to take us back a bit to what you were saying about grassroots mobilization, and I want to bring us a bit closer to home — to our region, the Eastern Mediterranean, the Middle East, whatever you want to call it — where we have seen massive mobilization and support for the Palestinian liberation struggle, in particular in Jordan and Bahrain.

In Jordan, we’ve seen consistent demonstrations over the last year that have brought thousands and thousands out onto the streets. And of course, Jordan has a very sizable Palestinian refugee population — I think over half of the population of Jordan is of Palestinian origin. And then also in Bahrain, we’ve seen very large protests take place in support of Palestinians amidst the genocide. At the same time, these protests have been met with brutal crackdowns and oppression in Bahrain, perhaps more so than in Jordan.

We’ve seen that in other countries where the authoritarianism is much more oppressive, like Egypt, there have been small protests as well. And all of this stands in direct contrast to the Arab regimes themselves, which by and large have been complicit in the genocide through normalization, through active diplomatic and trade ties, and even military coordination.

I think what has spoken to me amidst all of this is yet again how Palestine is serving that role as the linchpin of regional liberation, as it were — how the mobilization around Palestine inevitably always leads to critique and to rejection of domestic status quos. In Bahrain, for example, someone said that the government is so fearful of its own people’s just demands that it can’t even stomach children protesting for other people’s freedom, let alone their own. This comes after a huge wave of arrests in Bahrain, including of children.

And it brings me to thinking about the writing and work of Alaa Abd El-Fattah, a prominent writer and political prisoner in Egypt, who once wrote that the roots of the Egyptian revolution lie in the solidarity demonstrations with the Second Intifada.

I think what’s clear, or becoming even clearer amidst massive regional normalization, is that the Palestinian liberation struggle is not just about Palestine — it’s actually about the liberation of the entire region. And perhaps that links quite nicely with this question about decolonization and the urgent need for conversations around that. I think those conversations certainly have to happen in the Palestinian context and in Palestinian spaces, but they also have to happen beyond — in particular in the region, considering the massive complicity of Arab regimes.

But what does decolonization of Palestine mean for the neighboring countries? Can the decolonization, can the liberation of Palestine happen whilst those regimes are still in place?

Tareq Baconi 32:48

I’ve always thought of Palestinian liberation as being inextricably linked with the region and with its Arab depth, for various reasons. And when you talk about these regimes, when you talk about their complicity in genocide, I think of most of these regimes as being part of the post-colonial order — in the sense that they are authoritarian powers that rose after independence was declared, ingratiated into the Western sphere, not necessarily serving their people. They are regimes that are oppressing their people, they’re anti-democratic. Putting Palestine aside and thinking about all of the basic measures of a good human life, those are severely lacking across the Middle East.

That’s the reason why in 2010 and 2011, revolutions erupted in various countries throughout that post-colonial order — post-colonial in the sense that independence had been gained, but neocolonial in the sense that these regimes are neither legitimate nor chosen by the people, and are absolutely backed by foreign powers. Those regimes are not representative of the Arab street, and they have in the past co-opted the question of Palestine to further their own interests.

So that dialectic — where Palestine is instrumentalized or used in order to further oppression in these various countries — is still one that we see today. Even if we look at countries like Jordan or Egypt, they’re dealing with Palestine insofar as they have to address their existential worries about what might happen if Israel ethnically cleanses Palestinians out of historic Palestine, but they’re not in any way acting beyond that in terms of pushing solidarity or actively trying to engage in the quest for Palestinian liberation.

They each have their own domestic concerns. Some of them are existential. And so the order that we’re in is one whereby both Palestinians and Arabs and the wider inhabitants of that region are living under settler colonialism and under authoritarianism. And both of these things are linked and reinforcing and mutually constitutive.

Now, if we think about this moment in time where Israel is expanding its genocide and starting to attack countries throughout the region — systematically carrying out attacks across Lebanon in a way that I fear might destabilize the country and push us towards sectarian violence and civil war — what Israel is doing, and this is openly being debated now, is remaking the Middle East. What is this idea that they have? This idea is that there would be regime change in Iran, decapitating the head of the octopus, and changing Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Yemen, Egypt in a way that furthers the Israeli agenda and strengthens the kind of relations that we saw in the Abraham Accords between the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Israel. This is a vision of a region where Israel, with the support of the US financially, militarily, and diplomatically, is rising as a regional power, with countries that are essentially doing its bidding in terms of stabilizing the region and maintaining anti-democratic norms. It’s reshaping the Middle East in its favor.

Now, this is a fantasy. This will never happen. We understand what regime change operations do. We understand the arrogance and the idiocy of that kind of top-down effort to reshape regions — and the racism of reshaping regions, certainly in this case, to meet Western demands. But this is the reality we’re in. This is what colonialism in the form of Zionism is doing in the region. This is the vision for what the new Middle East is.

And so when we’re thinking back to the point about decolonization — yes. Thinking about decolonization in Palestine is part and parcel of thinking about decolonization in the region. It’s thinking about how these governments serve their people, not foreign interests. What does it mean to have a life of dignity, of good employment, good health, good education in the region today — not in a way that gives up political aspirations, but one that affirms the right to sovereignty and the right to have a political project that is one’s own.

I think we haven’t figured out what that looks like in the region yet, because the forces against us are very powerful. And to take us back to Alaa Abd El-Fattah’s point in his book — one of the quotes that I love is when someone asks him what they can do to show solidarity or support the struggle in Egypt, and he says, fight for democracy in your own country. And I think that’s right. The struggles in the Arab world are reinforcing the struggle in Palestine and vice versa. And I think that’s how we should be thinking about decolonization in the region.

Yara Hawari 38:01

I think we’ll leave it there. Thank you so much for joining me on this episode of Rethinking Palestine.

Tareq Baconi 38:07

Thank you for having me.

Yara Hawari 38:13

Rethinking Palestine is brought to you by Al-Shabaka, the Palestinian Policy Network. Al-Shabaka is the only global independent Palestinian think tank whose mission is to produce critical policy analysis and collectively imagine a new policymaking paradigm for Palestine and Palestinians worldwide. For more information or to donate to support our work, visit al-shabaka.org. And importantly, don’t forget to subscribe to Rethinking Palestine wherever you listen to podcasts.

Tareq Baconi serves as the president of the board of Al-Shabaka. He was Al-Shabaka’s US Policy Fellow from 2016 – 2017. Tareq is the former senior analyst for Israel/Palestine and Economics of Conflict at the International Crisis Group, based in Ramallah, and the author of Hamas Contained: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance (Stanford University Press, 2018). Tareq’s writing has appeared in the London Review of Books, the New York Review of Books, the Washington Post, among others, and he is a frequent commentator in regional and international media. He is the book review editor for the Journal of Palestine Studies.

Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network is an independent, non-partisan, and non-profit organization whose mission is to convene a multidisciplinary, global network of Palestinian analysts to produce critical policy analysis and collectively imagine a new policymaking paradigm for Palestine and Palestinians worldwide.