This section assumes that the Israeli regime would determine the collapse, dissolution, and/or reconfiguration of Palestinian Authority (PA). The analysis therefore addresses the form and structures of the Palestinian education system if Israel were to take charge of Palestinian affairs completely.

An Israeli Decision

Should the Israeli regime dissolve the PA, the latter’s responsibilities would become those of the Israeli military governor. In other words, the education of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, would be regulated by the Israeli regime; this refers to the Israeli army, the Israeli military governor, Israeli universities, and Israeli practitioners in the field of education. They would advise on structures, content, and planning to ensure that educational venues do not transform into political spaces for popular mobilization. Were it not for this possibility, Israel would entrust the education of Palestinians entirely to international parties, including UNRWA.

Assigning Palestinian education to UNRWA would entail two major issues that run counter to the Israeli settler-colonial regime’s impetus to eliminate the Palestinian presence. The first is that Israel would become a passive actor in shaping Palestinian consciousness at a moment when it would perceive an urgent need to do so, especially in the wake of any annexation of the West Bank, or parts thereof, or the disappearance of the PA as a mediator that prevents direct confrontation. The second is that maintaining UNRWA, the traditional candidate to fill this role, would mean affirming the Palestinian identity of refugees, as well as the history and narrative of their indigeneity — elements Israel has long striven to distort and dissolve.

For this reason, too, the Israeli regime would not leave the responsibility of Palestinian education to the Palestinians themselves, should it dissolve the PA. That is, popular education committees run by Palestinians, such as those that emerged during the First Intifada when Israel shut down schools and universities, could allow Palestinians to rebuild their collective body, including by inculcating economic resilience, which would not be in the regime’s interest.

The following sections discuss the shape of the Palestinian education sector should the Israeli regime become its curator.

Funding and Priorities

The Israeli regime has experience running parallel education systems in 1948 territories, one for Palestinians and another for Jewish Israeli citizens. It also maintained such an arrangement during its occupation of Gaza and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, in 1967. In these spaces, the bifurcated system has resulted in the marginalization of education in Palestinian communities; the Israeli regime did not build a single school or university, nor did it develop curricula. Rather, it used its grip on the education sector to eliminate Palestinian national goals and block mass mobilization and popular education.

Should Israel dissolve the PA, this would lead to minimum spending on the education sector, relative to spending on Israeli citizens’ education and to current PA levels of spending on education. The Israeli regime might even evade this burden by accepting education funding from international and Arab parties, provided that it maintains control over the management of the sector’s structures, bureaucracy, human resources, and content.

Quality

Should the Israeli regime dissolve the PA and absorb Palestinians as citizens, it would limit their education to low-wage skill development. Such education would prevent them from joining universities and educational institutions abroad. Indeed, there is precedent for this. Since its inception in 1949, UNRWA has sought to give Palestinian refugees lower-quality education in comparison to their counterparts in host countries, in order to facilitate their integration by ensuring their inferiority and thus, their acceptance by host communities. Similarly, the Israeli regime would exploit its control over education to ensure Palestinians remained with as few economic and intellectual opportunities as possible.

The Israeli regime’s ongoing practices show that it has not and will not undertake any effort to advance the quality of Palestinian education. Naturally, it would also attempt to block Palestinian access to international education initiatives, such as “Education for All” and others that enhance the quality of education.

Infrastructure

Even if the PA were to collapse, Palestinian education would be managed by several parties, including UNRWA, the Israeli military governor, the private sector, and/or the Islamic waqf, as it is managed today in East Jerusalem. However, Israeli regime authorities would have the final say on the sector’s objectives, functions, management, quality, and content. Even if there were to be other parties providing educational services, they would be directly or indirectly subject to Israeli oversight. For example, the private sector would require approval from Israel in its pedagogy and curricula, while UNRWA would continue to rely on the logic of humanitarian relief work.

Teachers would be chosen in a manner that ensures they are not biased toward the Palestinian national cause. Joining the new education sector would thus be contingent on political affiliation and previous political activity. As such, Israeli intelligence services would not only have the final say in hiring, but would also monitor the activities of employees thereafter. In this context, education would be marketed as a matter of human capital crucial to the development of Gaza and the West Bank, and any Palestinian attempts to politicize it would be viewed as irresponsible.

Further, the Israeli regime would not allow teachers to form their own associations and unions in a democratic and transparent manner. Instead, it might create an alternative body composed of Palestinians that acts as a mediator between teachers and those at the top of the centralized administrative hierarchy. This body would be responsible for receiving and handling complaints in a way that thwarts teachers from turning into a political force capable of influencing decision-making in the education sector.

Palestinian administrative bodies, and educational districts and directorates, would be centralized and headed by Israeli committees created specifically to manage Palestinian education. They would include sociologists, anthropologists, educationalists, and others working in Israeli universities and research centers. These committees would include experts who advise on how best to control or eliminate the indigenous identity of Palestinians, as well as security and intelligence agents who report directly to the military governor.

Israel would likely preserve the laws that regulate the educational process, especially if consistent with its objectives — as it has done in the West Bank and Gaza since 1967 — and would continue to do so through military orders. It is therefore unlikely that Israel would implement its existing laws in order to prevent any convergence of Palestinian and Israeli rights under the law.

Content (Curricula)

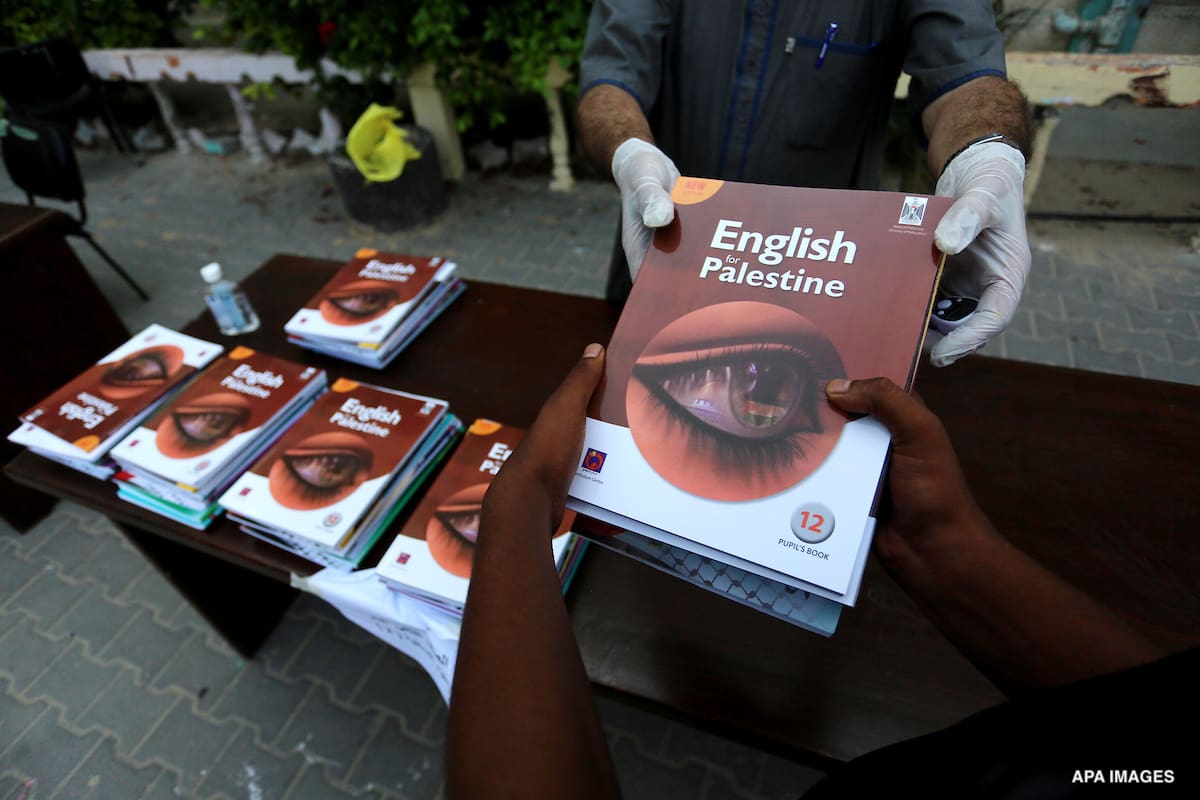

Palestinian curricular development would depend on the details of the PA’s collapse. Most likely, the collapse of the PA would not result in Israel’s absorption of the Palestinian population as citizens. Therefore, Palestinian curricula would likely evolve distinctly from Israel’s. Israel would maintain the current Palestinian curricula with revisions, especially to content conveying the political aspirations of the Palestinian people. Indeed, Israel did this upon occupying the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and Gaza in 1967; through military orders, it maintained the use of edited versions of the Jordanian and Egyptian curricula and never invested in curriculum development or teacher training.

Certainly, the Israeli regime would strategically neglect the Palestinian education sector; new curricula would not be developed nor would existing curricula be periodically updated. The outdated curricula would graduate generations disconnected from modern technology, regional contexts, and their own Palestinian heritage. This approach would ensure the Palestinian labor force’s dependence on the Israeli labor market and economy. Even if a Palestinian sub-economy or parallel economy emerged, it would be fragile and incapable of growth.

Mohammed Alruzzi is a Lecturer in Childhood Studies at the University of Bristol, the UK. He earned his PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of Fribourg, Switzerland. Before that, he completed his Master’s degree in Childhood Studies at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, UK. Alruzzi has worked with many international non-governmental organisations and UN agencies, including Mercy Corps, Terre des Hommes, the Norwegian Refugee Council, World Vision and UNICEF. Through his work experience, Mohammed has developed extensive multidisciplinary expertise in children issues. His research interests include child labour, child detention and education policy.