This scenario presumes that economic conditions in the West Bank and Gaza will persist as they have for the last few years. These conditions are outlined below.

The Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic

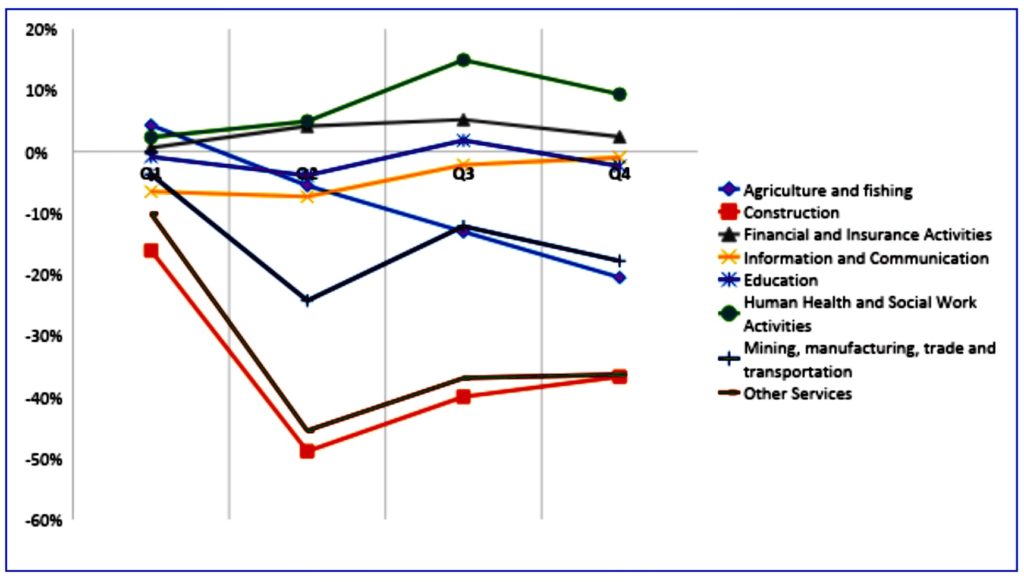

After years of neoliberal policies combined with an inflow of international aid between 2008 and 2013, which led to an illusion of growth and development under occupation, economic activities have been in a state of contraction. GDP per capita in the West Bank and Gaza declined between 0.8% and 1.3% from 2017 to 2019. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic heavily impacted economic activity in the West Bank and Gaza, where estimates by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for 2020 indicate a decline in GDP per capita by 13.7%, and around 14% of employed persons have temporarily or permanently lost their jobs. The unemployment rate increased from 25.3% in 2019 to 25.9% in 2020. Still, it is important to note that this rise is due to a drop in labor force participation from 44% in 2019 to 41% in 2020. This drop was considerably higher in Gaza than in the West Bank; participation decreased from 46% to 44% in the West Bank and from 41% to 35% in Gaza. These reductions of the labor force reflect an increasing number of discouraged workers who do not perceive any employment opportunity in the near future.Since the outbreak of COVID-19, economists have been debating the shape of recovery, describing either a quick V-shaped recovery or a slow L-shaped recovery. A fundamental part of the debate is the fact that the Palestinian economy is unable to access its resources due to the Israeli occupation. Moreover, the pandemic occurred while the Palestinian Authority (PA) was in fiscal crisis due to the Israeli regime’s retention of clearance revenues to the PA from customs and VAT taxes. As a result, and as the figure below shows, the Palestinian economy has in fact followed a K-shaped recovery, where some sectors recovered quickly or even benefited in the third and fourth quarters of 2020, but other sectors remain behind their 2019 levels. Figure 1: Annual quarterly percentage change in value added of economic sector between 2019 and 2020

The Palestinian health sector, for example, expanded during the pandemic, whereas the construction and services sectors are the least likely to recover. The agriculture and fishing sector has experienced a continuing decline since the second quarter of 2020. Unlike in other sectors, this decline persisted in the third and fourth quarters, with the value added in the fourth quarter around 20% lower than it was in the fourth quarter of 2019. This continued decline is driven by access restrictions to agricultural land in Area C of the West Bank, to water sources, and to fisheries in Gaza, in addition to the lack of PA policies to help the sector. The more restricted sectors are increasingly less able to cope with sudden shocks.

Further, the health, education, financial, and information and communication sectors, which recruit more high-wage labor, had fast recoveries or were less affected by the crisis, whereas the agriculture, construction, manufacturing, trade, and other services sectors that tend to employ low-wage labor are experiencing much slower recoveries. This uneven recovery will inevitably lead to widening inequality in income distribution and opportunity.

Economic conditions in Gaza have been deteriorating during the past five years, exacerbated by the outbreak of the pandemic in 2020. The World Bank estimated that since Israel’s May 2021 attack, Gaza’s poverty rate has increased to around 50-60% of households, and that more than two thirds of Palestinians in Gaza are food insecure. The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia estimated that poverty may affect around two thirds of Palestinians in Gaza within the next six years if the blockade is not lifted. This continuing deterioration of life is expected even without further assaults by the Israeli regime.

Given the fragility of Palestinian productive sectors, the Palestinian economy is increasingly vulnerable to any future political, economic, or fiscal shock. The vulnerability of the economy will lead Palestinians to seek work in 1948 territories and in Israeli settlements in the West Bank, which will subject them to the Israeli permit system.

The Post-Oslo Economic Reality

The trade deficit in the West bank and Gaza has increased since the Oslo Accords; in 2019, imports were four times greater than in 1995. A trade deficit must be financed by capital inflows from abroad. Indeed, since the PA’s establishment in 1994, the role of international aid to Palestinians has emphasized the economic dependence of Palestinians on the Israeli economy and the policies of the Israeli occupation. Although international aid declined in recent years due to former US president Donald Trump’s suspension of funds to the PA and UNRWA, the new US administration under Joe Biden has resumed aid. While the resumption of aid to UNRWA will help it maintain and reestablish some of its services, notably in Gaza, the effect of international aid on Palestinians remains questionable. Without a redistribution of aid to develop the productive sectors, and without political will to end the Israeli occupation, aid will only increase consumption and further destroy the productive sectors. Due to the growing trade deficit, the Palestinian trade sector, which mostly deals in imported products, has been expanding since 2008. This sector represented 21.3% of Palestinian GDP in 2019 compared to 9% in 2008. Trade is the only sector with a rising average in labor productivity since 2001. The productivity peak between 2010 and 2011 was associated with an increase in private credit facilities to Palestinians. But an increase in productivity without an increase in wages at the same rate implies rising inequality and the concentration of wealth in the hands of traders with Israel. Indeed, the expansion of the trade sector resulted in a new class of elites in the West Bank, who have benefited from the Israeli Civil Administration through special permits, whereby their staff and families are allowed to enter 1948 territories with special arrangements. This has contributed to flooding the Palestinian market with Israeli products, many of which are marked at relatively low prices, especially agricultural products. This significantly harms local Palestinian producers. Moreover, the dominance of elite traders over the trade sector has only bolstered their political influence. The expansion of private credit facilities since the neoliberal turn post-Oslo has additionally furthered financial vulnerability. That is, loan expansion has led to higher non-performing loans, with the rate of these loans increasing in the last four years from 2.32% in 2017 to 4.2% in 2020. Private credit facilities have not been productive; in 2020, 22.9% of private loans were given for consumption purposes and vehicles, and 23% for construction and real estate. A little more than 19% of private credit facilities were for trade activities. Loss of household income makes it difficult to pay for consumption or real estate loans. This was triggered by the PA’s inability to pay salaries for several months, by Israeli restrictions on movement to access places of work in 1948 territories, and by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Palestine Monetary Authority reported, for instance, that the rate of returned checks increased at the beginning of the pandemic from 11% in March 2020 to 40.7% in April 2020. Oslo likewise institutionalized Palestinian economic dependency on the Israeli regime, including through the Israeli Civil Administration. Although its role in the West Bank and Gaza decreased after the 1993 Oslo Accords, it has been restructured to represent a quasi-government in the West Bank. It no longer only issues worker, patient, and construction permits, but now puts forth detailed plans and budgets. For example, the Civil Administration now engages with Palestinian farmers in Area C, granting them access to water, infrastructure, and saplings for agriculture. The administration likewise arranged a project, under the supervision of the Quartet, intended to streamline trade between Israel and select Palestinian business owners. The project sought to ease and expedite Palestinian travel and export while increasing Israeli surveillance over the production process. To be sure, economic dependence on the Israeli regime is not only a result of military occupation; it is an institutionalized process that is expanding and replacing the role of the PA in regulating Palestinian economic activities. An important feature of this economic dependence is trade with Israel. Imports from Israel represent around 60% of imports to the West Bank and Gaza, and exports to Israel represent around 83% of Palestinian exports. As such, Palestinian households and businesses heavily depend on ease of trade with Israel, which can be subject to political decisions that manifest in Israeli closure policies and delays in security checks at Israeli ports. In light of the continuing decline of the productive sectors and dominance of the trade sector by corrupt Palestinian elite, middle-class workers are getting poorer, supplying their labor to the Israeli market or the trade sector. These workers are increasingly subjugated to the Israeli system of control, and will continue to be so long as the status quo persists.

Al-Shabaka Policy Member Tareq Sadeq is a Palestinian refugee from the village of Majdal Sadeq near Jaffa and currently lives in Ramallah. Tareq holds a Ph.D in economics from the University of Evry Val d’Essonne in France, where he was engaged in the Palestine solidarity movement and served as head of the General Union of Palestinian Students (GUPS). Currently, Tareq is assistant professor in the Department of Economics at Birzeit University. He has published on monetary policy, macroeconomics, econometrics, labour economics, income inequalities, and entrepreneurship. He is also a researcher in Palestine’s Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM).