The education sector is expected to continue to be negatively impacted by the surrounding political and economic conditions should the status quo persist. That is, if current conditions persist, it is unlikely that Palestinians will achieve progress in enhancing the quality of their education sector. This section outlines the current education sector in the West Bank and Gaza in order to examine the repercussions of the continuation of the status quo.

Funding and Priorities

For the past decade, around 15-18% of the PA budget has been allocated annually to the education sector. This is relatively substantial compared to other countries in the region, but is significantly lower than the PA’s spending on the security sector. Importantly, most government spending on education is allocated to salaries and does not consider the need to develop the sector toward decentralization. Moreover, spending remains focused on basic education rather than higher education, which impedes the creation of a sustainable local economy. This is significant considering the fact that Palestinian society across the West Bank and Gaza is young, with children under the age of 18 constituting 44.2% of the population (42% in the West Bank and 47.5% in Gaza).

The PA’s public budget suffers from an annual deficit that affects the public sector and, by extension, the salaries of education sector employees, who have been receiving salaries in installments in recent years. The political division between Fatah and Hamas aggravates this deficit and burdens an already skewed budget, as a sizable portion of PA employees in education have been asked not to report to schools in Gaza since Hamas took over the PA institutions there in 2006 (though they continue to receive their salaries). In addition, the development cost of the Ministry of Education as well as the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research relies largely on international projects and is therefore disconnected from local education priorities. These are often pilot projects that conclude once funding dries up, thereby impacting the sector’s sustainable development process.

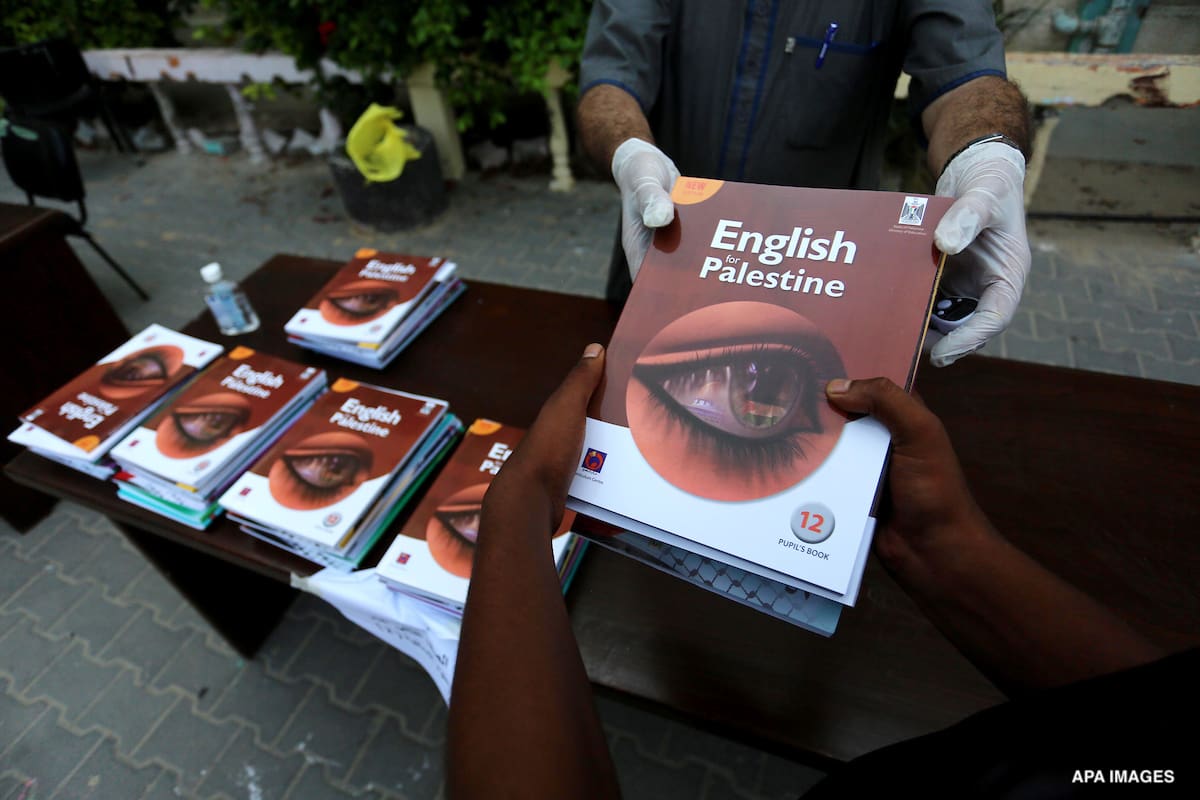

Moreover, the various donors funding the sector impose their agendas and conditions, negatively impacting educational structures and content. For example, after Israeli incitement against Palestinian curricula, the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs froze nearly half of its aid and conditioned its resumption on the PA revising its textbooks. Palestinian education thus reflects the interests of international donors more than those of Palestinian teachers and students.

Quality

While education in Palestine has experienced quantitative improvements in recent years — including affiliation, enrollment, and continuation rates — qualitative progress continues to lag behind. According to many indicators, the Palestinian education sector is in continuous decline and fails to meet generally accepted quality standards, including those pertaining to curricula and pedagogy. Conditions for teachers are an important indicator for measuring the quality of the education sector. Teachers in Gaza and the West Bank experience poor conditions, not least of which are low median salaries, a decline in their social status, a lack of motivation to work, and difficult working conditions in schools.

In terms of quality of knowledge, current Palestinian curricula overlook practical training and life skills, and do not address entrepreneurial education, while pedagogies do not encourage research and inquiry. Indeed, the evaluation methods used in Palestinian schools rely on paper-based examination to gauge students’ memorization. These problems also extend to higher education, which offers repetitive academic programs, is limited in terms of global application, and suffers from a gender gap by failing to convert the high rate of female enrollment in basic and higher education into labor market participation.

Infrastructure

The current centralized and bureaucratic infrastructures of Palestinian governance obstruct the achievement of national and international educational goals, which go beyond quantitative enrollment rates. These structures fail to utilize the resources available to realize these goals, and centralization hinders the education sector’s capacity to respond to the varying economic and social realities across different Palestinian territories. Moreover, political fragmentation and the need to operate within different geographies (the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and Gaza) hamper the creation of an education system that is coherent and responsive to the social, political, and economic challenges of each context.

Indeed, the current management of the education sector reflects a bitter reality: With several actors involved (the PA, the Israeli regime, the private sector, and UNRWA), fragmented control has led to unstandardized educational programming and regulation. The proliferation of actors has been aggravated by the fact that the Ministry of Education and Higher Education has been split into two entities — the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research — and again merged five times.1

In addition, Palestinian political division has caused discord between the branches of the education ministries in Gaza and the West Bank, which has deepened fragmentation in education administration and content. This was particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, which exposed the weak infrastructure of Palestinian educational institutions and their failure to keep abreast of the requirements of safe education, including with regard to adopting and implementing digital solutions as an alternative to face-to-face education. Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) data indicates that only 51% of households in the West Bank and Gaza with children aged 6-18 enrolled their children in distance learning activities during the closure period between March and May 2020. In addition, 48.5% of households indicated that the lack of an internet connection at home prevented children from participating in educational activities. The ongoing reality of political division and divided leadership thus cannot secure robust education infrastructure that can promote liberation.

Content (Curricula)

The creation of the first Palestinian curriculum began following the establishment of the PA in 1994, and by the end of the 2005-2006 school year, curricula for all grades were completed. However, none of these curricula have shifted the education model from memorization to learning and discovery, and from the centrality of the teacher to the individuality of the learner. Current curricula are information-heavy and lack an overarching holistic approach stemming from a clear political vision. They desperately require updating because, as they stand, they fail to promote creativity, critical analysis, and problem solving, and are fundamentally disconnected from Palestinians and their aspirations for the future.2

- The Ministry of Education and Higher Education was instituted in 1994 to oversee basic and higher education. In 1996, this ministry was split into two ministries following the formation of the new Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research. These two ministries continued to operate in parallel until they were merged in 2002. A decade later, the ministry was split again into two ministries only to be merged again after one year (2013). The two were split yet again in 2019.

- In-depth research is needed into the values that curricula promote, including an analysis of their implications on different aspects of society: level of education, equality, freedom, social justice, gender, the relationship between religion and the state and between individuals, the nature of political authority and the separation of powers, poverty and unemployment, and the provision of care for marginalized communities, among others.

Mohammed Alruzzi is a Lecturer in Childhood Studies at the University of Bristol, the UK. He earned his PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of Fribourg, Switzerland. Before that, he completed his Master’s degree in Childhood Studies at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, UK. Alruzzi has worked with many international non-governmental organisations and UN agencies, including Mercy Corps, Terre des Hommes, the Norwegian Refugee Council, World Vision and UNICEF. Through his work experience, Mohammed has developed extensive multidisciplinary expertise in children issues. His research interests include child labour, child detention and education policy.