- Topics

-

Topics

See our analysis on civil society and how it shapes culture, politics, and policies

Read our insights on the shifting political landscape and what it means for Palestine

Learn more about the policies and practices shaping the Palestinian economy

Strengthen your understanding of the unique conditions for Palestinian refugees across the Middle East

-

- Analysis

-

Analysis

In-depth analysis on existing or potential policies that impact possibilities for Palestinian liberation.

Insights and perspectives on social, political, and economic questions related to Palestine and Palestinians globally.

Concise analysis into a specific policy, its background and implications.

Commentary that brings together insights from multiple analysts.

Compilations of past Al-Shabaka works surrounding a specific theme.

Longer-form, ad hoc projects that seek to confront research questions outside the scope of our regular analysis.

A policy-driven research initiative by Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network.

Our monthly webinar series that brings together Palestinian experts.

Featured

This policy brief introduces de-healthification as a framework for understanding Israel’s systematic destruction of Palestinian healthcare infrastructure, particularly in Gaza. Rather than viewing the collapse of Gaza’s health system as a secondary outcome of the genocide, the brief argues that it is the product of long-standing policies of blockade, occupation, and structural neglect intended to render Palestinian life unhealable and perishable. By tracing the historical evolution of de-healthification, this brief argues that naming the process is essential for accountability. Because intent is revealed through patterns of destruction rather than explicit declarations, the framework of de-healthification equips policymakers, legal bodies, and advocates to identify healthcare destruction and denial as a core mechanism of settler-colonial control. Layth Malhis· Jan 11, 2026The global reckoning that followed October 7, 2023, marked a profound rupture in how Palestine is understood worldwide. The Gaza genocide exposed how Israeli mass violence is not exceptional or reactive, but foundational to the Zionist project. What was once framed as a “conflict” to be managed is now widely recognized as a system of domination to be dismantled. It ushered in a shift away from the technocratic language of peace processes and toward an honest confrontation with the structural realities Palestinians have long named: settler colonialism, apartheid, and the ongoing Nakba. The commentary argues that the Israeli genocidal campaign in Gaza has radicalized the world. When crowds march through global capitals demanding a free Palestine, they simultaneously articulate demands for the abolition of racial capitalism, extractive regimes, climate injustice, and all forms of contemporary fascism. In this moment of radical clarity, Palestine becomes a lens through which the underlying architecture of global domination is laid bare—and through which new horizons of collective freedom emerge.

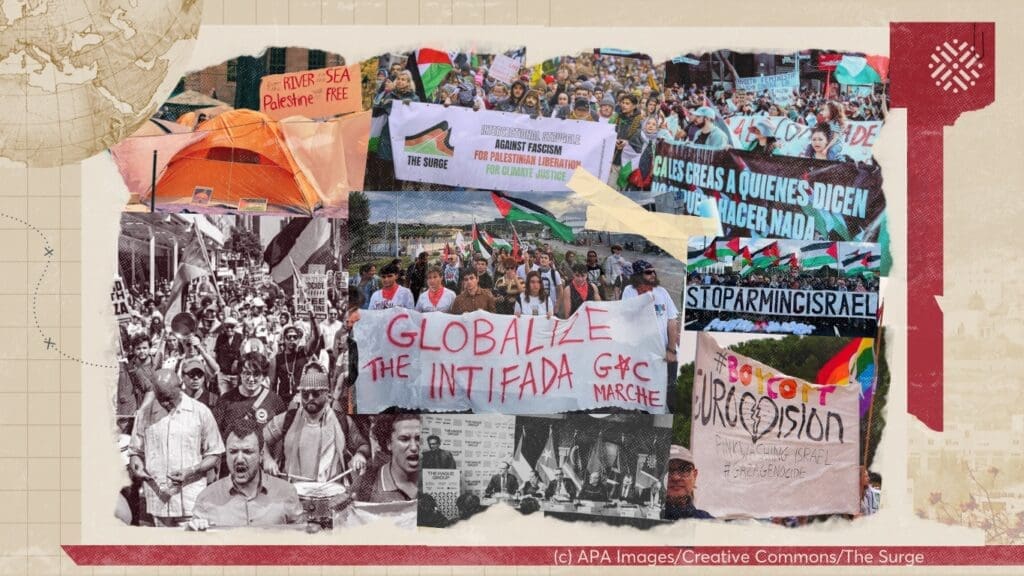

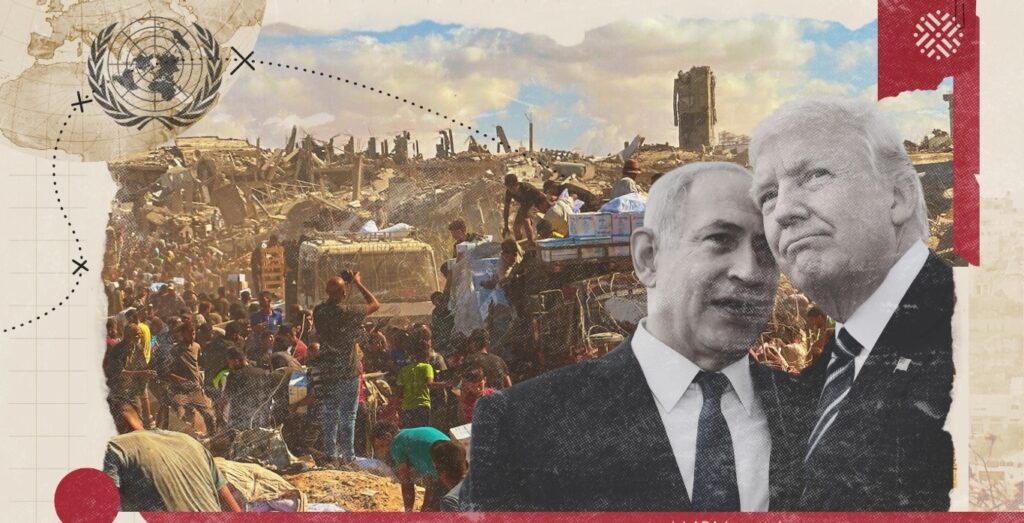

Layth Malhis· Jan 11, 2026The global reckoning that followed October 7, 2023, marked a profound rupture in how Palestine is understood worldwide. The Gaza genocide exposed how Israeli mass violence is not exceptional or reactive, but foundational to the Zionist project. What was once framed as a “conflict” to be managed is now widely recognized as a system of domination to be dismantled. It ushered in a shift away from the technocratic language of peace processes and toward an honest confrontation with the structural realities Palestinians have long named: settler colonialism, apartheid, and the ongoing Nakba. The commentary argues that the Israeli genocidal campaign in Gaza has radicalized the world. When crowds march through global capitals demanding a free Palestine, they simultaneously articulate demands for the abolition of racial capitalism, extractive regimes, climate injustice, and all forms of contemporary fascism. In this moment of radical clarity, Palestine becomes a lens through which the underlying architecture of global domination is laid bare—and through which new horizons of collective freedom emerge. Tareq Baconi· Dec 21, 2025Inès Abdel Razek and Munir Nuseibah joined Al-Shabaka for a conversation on the politics behind the UNSC resolution, the implementability of the US-Israeli plan, and the scenarios now being advanced for Gaza and for Palestine more broadly.

Tareq Baconi· Dec 21, 2025Inès Abdel Razek and Munir Nuseibah joined Al-Shabaka for a conversation on the politics behind the UNSC resolution, the implementability of the US-Israeli plan, and the scenarios now being advanced for Gaza and for Palestine more broadly.

-

- Resources

- Media & Outreach

- The Network

How Palestinian Hunger Strikes Counter Israel’s Monopoly on Violence

As these words were being written, three Palestinian prisoners were on hunger strike in protest against their imprisonment without trial, a practice cloaked by the anodyne sounding term “administrative detention”. Sami Janazra was on his 69th day and his health has sharply deteriorated, Adeeb Mafarja was on his 38th day, and Fuad Assi was on his 36th. These prisoners are amongst at least 700 Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails who are currently being held in administrative detention, a practice that Israel routinely uses in violation of the strict parameters set by international law.1

Palestinian political prisoners have long used hunger strikes as a form of protest in response to violations of their rights by Israeli authorities. Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association traces the first use of hunger strikes by Palestinian prisoners to as early as 1968. Since then, there have been over 25 mass and group hunger strikes with demands ranging from ending solitary confinement and administrative detention to improving imprisonment conditions and allowing family visits.

As more and more Palestinian prisoners are forced to embark on lengthy hunger strikes as a “last resort” form of protest by inflicting violence on their bodies until they win their rights, it is worth reviewing the use of this political tool across countries and centuries and spotlighting the way in which Palestinian prisoners are using it to counter Israel’s monopoly on violence within the prison walls.

Past and Present Use of Hunger Strikes

While the exact origins of hunger strikes – the voluntary refusal of food and/or fluids – are not well known, there are examples of their use in various historical periods and geographical locations. The earliest uses of hunger strikes are traced to medieval Ireland where one person would fast on the doorstep of another who had committed an injustice against them, as a way of shaming them. More recent and better-known uses of hunger strikes include those by British suffragettes in 1909, Mahatma Gandhi during the revolt against British rule in India, Cesar Chavez during the struggle for farm workers rights in the United States, and the prisoners incarcerated by the US in Guantanamo Bay.

There is great danger of irreversible physical harm to the body through hunger strikes including loss of hearing, blindness and severe blood loss.2 Indeed, death has been the outcome of many hunger strikes as in the case of the 1981 Irish Republican prisoners’ strike.

The demands by hunger strikers vary but are, in all cases, a reflection of broader issues and social, political and economic injustices. For example, the 1981 Irish Republican prisoners’ hunger strike demand for the return of Special Category Status reflected the broader context of “the troubles” in Northern Ireland.3[contextly_auto_sidebar]

One of the earliest Palestinian hunger strikes was the seven-day hunger strike in Askalan (Ashkelon) prison in 1970. During this strike the prisoners’ demands were written on a cigarette pack as they were prevented from having notebooks, and included a refusal to address their jailers as “sir”. The prisoners won their demand and never had to use ”sir” again, but only after Abdul-Qader Abu Al-Fahem died after being force-fed, becoming the first martyr of the Palestinian prisoners’ movement.

Hunger strikes at Askalan prison continued to be carried out through the 1970s. In addition, two more prisoners, Rasim Halawe and Ali Al-Ja’fari, died after being force-fed during a hunger strike at Nafha prison in 1980. As a result of these and other hunger strikes, Palestinian prisoners were able to secure certain improvements to their prison conditions, including being allowed family pictures, stationery, books and newspapers.

In recent years, ending the practice of administrative detention has been a persistent demand by Palestinian prisoners, given Israel’s escalation of its use since the outbreak of the Second Intifada in 2000. For example, the mass 2012 hunger strike, which involved nearly 2,000 prisoners, demanded an end to the use of administrative detention, isolation and other punitive measures including the denial of family visits to Gaza prisoners. The strike ended after Israel agreed to limit the use of administrative detention.

However, Israel soon reneged on the agreement, leading to another mass hunger strike in 2014 by over 100 administrative detainees pushing for an end to this practice. The hunger strike ended 63 days later without having achieved an end to administrative detention. The prisoners’ decision was reportedly influenced by the disappearance of three Israeli West Bank settlers and Israel’s large-scale military operations in the West Bank (which was followed by a massive assault against Gaza).

In addition, there have been several individual hunger strikes sometimes coinciding with or leading to decisions to begin wider hunger strikes. Indeed both the 2012 and 2014 hunger strikes were sparked by individual hunger strikes demanding an end to the use of administrative detention. The individual hunger strikers included Hana Shalabi, Khader Adnan, Thaer Halahleh and Bilal Diab, all of whom secured an end to their administrative detention. However, some of the individual hunger strikers were re-arrested after their release as in the case of Samer Issawi, Thaer Halahleh, and Tareq Qa’adan, as was Khader Adnan, who was released after a prolonged hunger strike protesting his re-arrest in 2015.

The Violence Israel Inflicts on Palestinian Prisoners

Israel continues to subject Palestinian prisoners to many forms of violence as has been well documented by human and prisoner’s rights organizations, as well as in the writings of prisoners and in a number of documentaries.4 In a 2014 report Addameer notes, “Every Palestinian who was arrested was subjected to some form of physical or psychological torture, cruel treatment including severe beatings, solitary confinement, verbal assault, and threats of sexual violence.”

In addition, and in violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention and the Rome statue, Israel has deported Palestinian detainees outside of the occupied territories and to prisons inside Israel, as well as threatening West Bank prisoners with deportations to the Gaza Strip if they do not confess. It also routinely and arbitrarily denies or restricts family visits. Prisoners are exposed to deliberate medical negligence and abuse, as well as restrictions on phone calls and access to lawyers, books, and television.

Furthermore, the Israeli authorities classify Palestinian political prisoners as “security prisoners” a classification that makes it legally possible to automatically subject them to many restrictions. This characterization denies Palestinian prisoners some of the rights and privileges enjoyed by Jewish prisoners – even those few who are labeled security prisoners – including home visits under guard, the possibility of early release, and the granting of furloughs.

The violence to which Palestinian prisoners are subjected must be seen within the context of Israel’s colonial project and its subjection of the entire population to different forms of violence, including the loss of their land, destruction of their homes, expulsion, and exile. It is worth recalling that since the Israeli occupation began in 1967, Israel has arrested more than 800,000 Palestinians, nearly 20% of the overall population, and 40% of the male population. This fact alone makes clear the extent to which arrests and imprisonment are a mechanism Israel uses to control the population while it dispossesses them, settling Israeli Jews in their place.

It is within this broader understanding of violence that hunger strikes emerge as a way in which Palestinian prisoners are able to counter the Israeli state’s various forms of violence.

Using the Prisoner’s Body to Subvert the State’s Power

Through hunger strikes, prisoners no longer remain silent recipients of the prison authorities’ ongoing violence: Instead, they inflict violence upon their own bodies in order to impose their demands. In other words, hunger strikes are a space outside the reach of the Israeli state’s power. The body of the striking prisoner unsettles one of the most fundamental relationships to violence behind prison walls, the one in which the Israeli state and its prison authorities control every aspect of their lives behind bars and are the sole inflictors of violence. In effect, prisoners reverse the object and subject relationship to violence by fusing both into a single body – the body of the striking prisoner – and in so doing reclaim agency. They assert their status as political prisoners, refuse their reduction to the status of “security prisoner”, and claim their rights and existence.

The fact that the Israeli state uses several measures to put an end to hunger strikes and to re-assert its power over the prisoners and over the use of violence demonstrates the challenge that the bodies of the hunger strikers pose to the Israeli state. Among other measures, the prison authorities continue to subject the striking prisoners to violence and torture. In fact, the violence to which the striking prisoners are subjected intensifies and changes form. For instance during the 2014 hunger strike, the striking prisoners were denied medical treatment and family visits and were shackled by their hands and feet to hospital beds 24 hours a day. They remained shackled when allowed to go to the bathroom, and the open bathroom doors denied them any right of privacy. The Israeli authorities also intentionally left food near the hunger strikers to break their will. Ex-hunger striker Ayman Al-Sharawna said, “They’d bring a table of the best food and put it next to my bed… Shin Bet knew I loved sweets. They used to bring all kinds of dessert.”

Israel has recently given legal cover to the force-feeding of hunger striking prisoners through the “Law to Prevent Harm Caused by Hunger Strikers”, which is tantamount to cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, according to the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture. The law is also in contradiction with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Malta on Hunger Strikes.

Israel also labels the striking prisoners “terrorists” and “criminals” to undermine their assertion of political agency and their efforts to reverse the object and subject of state violence. During the 2014 mass hunger strike, Israeli officials maintained that the hunger strikers were “terrorists.” Israeli Minister of Culture and Sport Miri Regev, one of the sponsors of the recent bill, said, “Prison walls don’t mean an action is not terrorism […] There is terrorism on the streets and this is terrorism in prison.” Gilad Erdan, Israeli Minster of Public Security declared that hunger strikes were a “new type of suicide attacks.”

The Vital Importance of National and International Support

Central to the success of any hunger strike is the ability of the strikers to mobilize communities, organizations and political bodies in their support and to exert pressure on the authorities to concede to the hunger strikers’ demands or negotiate an agreement.

Through hunger strikes, Palestinian prisoners have been able to continuously force their struggles onto the Palestinian and often the international political stage. Given that there are currently no alternatives through which prisoners can secure their freedom or a change in Israeli policies, the importance of mobilizing communities and political bodies around prisoners’ rights cannot be underestimated.

Grassroots, human rights organizations and official bodies both within and outside Palestine have mobilized during hunger strikes by Palestinian prisoners. The support has included daily gatherings, protests outside the offices of international organizations, calls on the Israeli government to heed the prisoners’ demands, and demonstrations outside prisons and hospitals. Local and international organizations including Addameer, Jewish Voice for Peace, Amnesty International, and Samidoun, among others, have highlighted the injustices faced by Palestinian prisoners to add to the pressure on Israeli authorities to concede to the prisoners’ demands and negotiate an agreement with them.

Furthermore, through these networks, the struggle of the Palestinian hunger strikers, and of the prisoners more broadly, is internationalized with parallels drawn to past and present injustices facing peoples worldwide. In reporting and analysis on the Palestinian hunger strikes, references are continuously made to the plight of Irish prisoners during the “troubles,” mass-incarceration in the US and conditions at Guantanamo Bay, among others. In this way the struggle of Palestinian prisoners becomes part of the growing solidarity movements and campaigns demanding justice for the Palestinian people. This helps to counter the Israeli labeling of them as “criminals” and “terrorists” and its monopoly over the discourse.

As with other forms of resistance within and outside prison walls hunger strikes are acts of resistance through which Palestinians assert their political existence and demand their rights. It is vital to sustain and nurture this resistance. In addition to giving strength to and supporting the prisoners in their struggle for rights, this form of resistance continuously and powerfully inspires hope among Palestinians at large and the solidarity movement. It is our responsibility to both support Palestinian prisoners – and to work for a time when Palestinians no longer need to resort to such acts of resistance through which their only recourse is to put their lives on the line.

Basil Farraj

Latest Analysis

The NCAG: Gaza’s Technocratic Turn to Genocide Management

De-Healthification: Israel’s Engineered Collapse of Palestinian Life

The World Radicalized by the Gaza Genocide

We’re building a network for liberation.

As the only global Palestinian think tank, we’re working hard to respond to rapid developments affecting Palestinians, while remaining committed to shedding light on issues that may otherwise be overlooked.