- Topics

-

Topics

See our analysis on civil society and how it shapes culture, politics, and policies

Read our insights on the shifting political landscape and what it means for Palestine

Learn more about the policies and practices shaping the Palestinian economy

Strengthen your understanding of the unique conditions for Palestinian refugees across the Middle East

-

- Analysis

-

Analysis

In-depth analysis on existing or potential policies that impact possibilities for Palestinian liberation.

Insights and perspectives on social, political, and economic questions related to Palestine and Palestinians globally.

Concise analysis into a specific policy, its background and implications.

Commentary that brings together insights from multiple analysts.

Compilations of past Al-Shabaka works surrounding a specific theme.

Longer-form, ad hoc projects that seek to confront research questions outside the scope of our regular analysis.

A policy-driven research initiative by Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network.

Our monthly webinar series that brings together Palestinian experts.

Featured

The announcement of the National Committee for the Administration of Gaza (NCAG), a 15-member technocratic body chaired by Ali Shaath, signals a shift toward depoliticized governance in Gaza amid ongoing genocide. Shaath, a Palestinian civil engineer and former deputy minister of planning and international cooperation, will lead an interim governing structure tasked with managing reconstruction and service provision under external oversight. While presented as a neutral technocratic governing structure, the NCAG is more likely to function as a managerial apparatus that stabilizes conditions that enable genocide rather than challenging them. This policy memo argues that technocratic governance in Gaza—particularly under US oversight, given its role as a co-perpetrator in the genocide—should be understood not as a pathway to recovery or sovereignty, but as part of a broader strategy of genocide management. Yara Hawari· Jan 26, 2026This policy brief introduces de-healthification as a framework for understanding Israel’s systematic destruction of Palestinian healthcare infrastructure, particularly in Gaza. Rather than viewing the collapse of Gaza’s health system as a secondary outcome of the genocide, the brief argues that it is the product of long-standing policies of blockade, occupation, and structural neglect intended to render Palestinian life unhealable and perishable. By tracing the historical evolution of de-healthification, this brief argues that naming the process is essential for accountability. Because intent is revealed through patterns of destruction rather than explicit declarations, the framework of de-healthification equips policymakers, legal bodies, and advocates to identify healthcare destruction and denial as a core mechanism of settler-colonial control.

Yara Hawari· Jan 26, 2026This policy brief introduces de-healthification as a framework for understanding Israel’s systematic destruction of Palestinian healthcare infrastructure, particularly in Gaza. Rather than viewing the collapse of Gaza’s health system as a secondary outcome of the genocide, the brief argues that it is the product of long-standing policies of blockade, occupation, and structural neglect intended to render Palestinian life unhealable and perishable. By tracing the historical evolution of de-healthification, this brief argues that naming the process is essential for accountability. Because intent is revealed through patterns of destruction rather than explicit declarations, the framework of de-healthification equips policymakers, legal bodies, and advocates to identify healthcare destruction and denial as a core mechanism of settler-colonial control. Layth Malhis· Jan 11, 2026The global reckoning that followed October 7, 2023, marked a profound rupture in how Palestine is understood worldwide. The Gaza genocide exposed how Israeli mass violence is not exceptional or reactive, but foundational to the Zionist project. What was once framed as a “conflict” to be managed is now widely recognized as a system of domination to be dismantled. It ushered in a shift away from the technocratic language of peace processes and toward an honest confrontation with the structural realities Palestinians have long named: settler colonialism, apartheid, and the ongoing Nakba. The commentary argues that the Israeli genocidal campaign in Gaza has radicalized the world. When crowds march through global capitals demanding a free Palestine, they simultaneously articulate demands for the abolition of racial capitalism, extractive regimes, climate injustice, and all forms of contemporary fascism. In this moment of radical clarity, Palestine becomes a lens through which the underlying architecture of global domination is laid bare—and through which new horizons of collective freedom emerge.

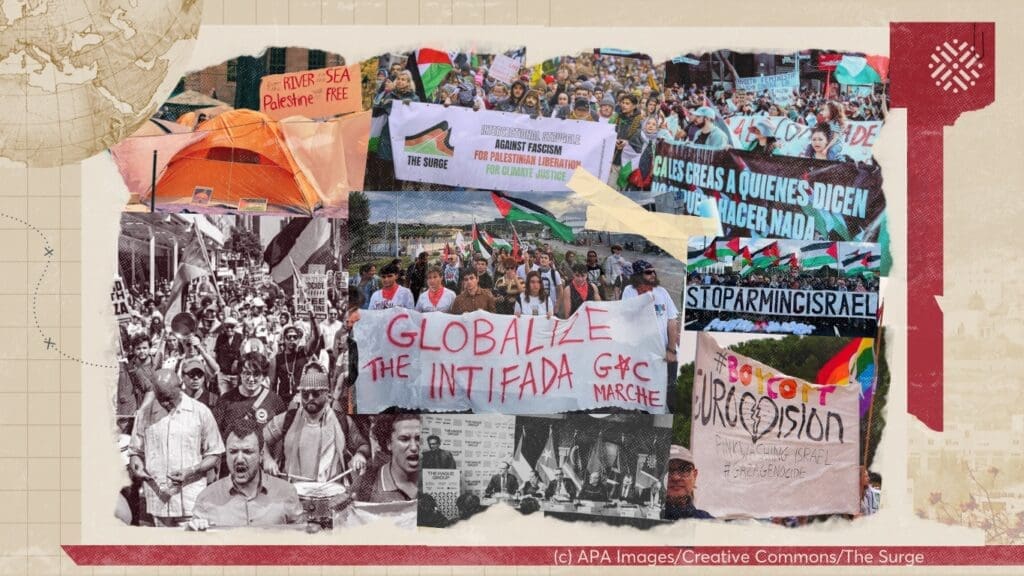

Layth Malhis· Jan 11, 2026The global reckoning that followed October 7, 2023, marked a profound rupture in how Palestine is understood worldwide. The Gaza genocide exposed how Israeli mass violence is not exceptional or reactive, but foundational to the Zionist project. What was once framed as a “conflict” to be managed is now widely recognized as a system of domination to be dismantled. It ushered in a shift away from the technocratic language of peace processes and toward an honest confrontation with the structural realities Palestinians have long named: settler colonialism, apartheid, and the ongoing Nakba. The commentary argues that the Israeli genocidal campaign in Gaza has radicalized the world. When crowds march through global capitals demanding a free Palestine, they simultaneously articulate demands for the abolition of racial capitalism, extractive regimes, climate injustice, and all forms of contemporary fascism. In this moment of radical clarity, Palestine becomes a lens through which the underlying architecture of global domination is laid bare—and through which new horizons of collective freedom emerge. Tareq Baconi· Dec 21, 2025

Tareq Baconi· Dec 21, 2025

-

- Resources

- Media & Outreach

- The Network

One Hundred Years and Counting: Britain, Balfour, and the Cultural Repression of Palestinians

Overview

If Palestinian poet Dareen Tatour passes over the perimeter of her home’s driveway in her village of Reineh in the Galilee, an alarm will sound at the British multinational security firm G4S and the Israeli authorities will be alerted. Israeli police arrested Tatour in the early hours of October 11, 2015 for her poem, “Qawem ya sha‘abi qawemhum” (Resist My People, Resist Them), which was posted to her YouTube account earlier that month. On November 2, Israel charged her with incitement to violence and support for a terrorist organization.

In January, after three months in prison, Tatour was placed under house arrest near Tel Aviv, far from her village. After a lengthy struggle, the prosecution conceded in July that she could be held in her family’s home. While Tatour’s trial proceeds, she will remain under house arrest and will continue to be monitored by G4S as a “threat” to Israel’s security.1

Such British complicity in the cultural repression of Palestinians is not a recent phenomenon. One can argue that it has its roots in the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which, by calling for the establishment of a nation for the Jewish people while all but disregarding the existence of the Palestinians inhabiting the land in question, set in motion the process of dispossession, exile, and social and cultural fragmentation that continues to the present day. And this was but the beginning of a British approach to the Palestinian people that has suppressed their culture and history.

Indeed, today, as Israel funnels substantial financial resources into promoting its cultural output internationally, the United Kingdom (UK) is taking measures to censor Palestinian cultural expression and creativity. From the involvement of private companies such as G4S in the house arrest of Tatour to ministerial moves to block the cultural boycott and stifle academic debate, while UK visas are frequently denied to Palestinian artists and educators, Britain’s repressive actions are aiding Israel by supporting its one-sided narrative – a narrative that helps Israel continue its occupation of Palestinian territory and deepen its apartheid regime.

There will likely be much scholarly and policy analysis of the fallout from the Balfour Declaration for Palestine and the surrounding countries over the past 100 years (including by think tanks such as Al-Shabaka.) This commentary makes the case for a focus on the cultural dimension and provides the background and arguments for such a focus by examining the British role, then and now.

Balfour and the Origins of Cultural Repression

Despite its devastating impact on Palestinians, the Balfour Declaration means little to most people in Britain. If you were to ask the average person on a UK street what it was, they would most likely know next to nothing about the document.

However, the British government is planning to commemorate the centenary of the declaration in November 2017. Earlier this year, former British Prime Minister David Cameron said he wanted the UK government to mark the anniversary together with the Jewish community “in the most appropriate way.” At the time, it was not altogether clear what he meant by “appropriate.” Today, we are none the wiser, but plans to mark the occasion are nonetheless still rumored to be in the pipeline, though now under the auspices of Britain’s controversial new foreign secretary, Boris Johnson.

In his brief but fateful 1917 declaration, then Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour proclaimed the British government would “use their best endeavors” to facilitate “the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people.” Thus, even before the British Mandate had officially begun, Balfour promised Palestine to the Zionist Federation without the consent of its Palestinian inhabitants. His concise erasure of Palestinian culture and history is found within the very vocabulary he used, referring to the indigenous, majority population only as “non-Jewish.”

Though Balfour did acknowledge Palestine’s inhabitants two years later, he assigned their lives less value than the Jewish people who would take possession of the land. He announced in a memorandum, “Zionism be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in an age-long tradition, in present needs, in future hopes, of far profounder import than the desires of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land.”

The logical outcome of this denial of Palestinian culture and history was the eventual dispossession and dispersal of the Palestinian population in 1948, followed by the demolition or Judaization of towns and villages emptied of their inhabitants.

The prejudicial sentiment expressed by Balfour underscores the UK’s relations with Israel to this day. It therefore comes as little surprise that the government did not consult with the UK’s Palestinian community before announcing its intention to mark the centenary.

Nevertheless, Palestinians are already mobilizing to take action against the UK for its historic role in the purloining of Palestine. Last year, Egypt’s “Popular Palestinian Campaign to sue the United Kingdom” initiated a case to “restore the right of the Palestinian people to their land.” In addition, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas recently announced that he intends to sue the UK government over the Balfour Declaration. He also accused Britain of supporting “Israeli crimes” since the end of its mandate over Palestine and called on the Arab League to help the Palestinian Authority launch its lawsuit.

The legacy of Balfour and the British Mandate includes a long history of Israel repressing Palestinian expression, from the plundering of Palestinian libraries and the imprisonment of Palestinian writers to the banning of Palestinian cultural activities and the obliteration of cultural sites and schools in Gaza.

Immediately after the establishment of the Israeli state in 1948, Palestinians who remained within the borders of what then became “Israel” were forbidden to study their cultural inheritance or to remember their immediate past.

An obituary of Mahmoud Darwish in 2008 recalled how, when he was eight years old, the young poet recited a poem at his school’s annual celebration of Israel’s birth about the inequality he noticed between the lives of Arab boys and Jewish boys. Afterward, the Israeli military governor summoned him. “If you go on writing such poetry” he said, “I’ll stop your father working in the quarry.” The utterance of the simplest of truths by a Palestinian child clearly frightened the Israeli military governor enough to threaten the livelihood of his family.

Then, as now, the Israeli authorities could not countenance the cultural expression of a Palestinian consciousness. Darwish went on to be imprisoned five times by the Israeli authorities, mostly charged with reciting poetry thought to be seditious and detrimental to Israel’s status and stability.

Attempts to stifle Darwish’s voice have continued beyond his death. In July 2016, Israel’s defense minister, Avigdor Lieberman, went so far as to equate the poet’s work to Mein Kampf after Israeli army radio unexpectedly broadcast Darwish’s poem, “ID Card.” Lieberman’s comments came after the Israeli culture minister, Miri Regev, called on him to stop funding the radio station on the grounds that it had “gone off the rails” and was providing a platform for the Palestinian narrative.

It would thus seem that very little has changed since the early days of Israel’s establishment. And recent moves by the UK to block the cultural boycott and stifle academic debate show a significant rise in the extent to which Britain has become openly involved in the censorship of those speaking out against Israel.

Current British Complicity

It is not only corporate entities such as G4S in the case of Dareen Tatour that are infringing on free speech on Israel’s behalf. At a time when international pressure on Israel is increasing, the UK government and a number of British institutions are moving in the opposite direction, deepening their support for a Zionist ideology bent on repressing Palestinian culture and history.

Efforts to freeze the funding of arts groups and productions deemed “pro-Palestinian” by Israel’s Culture Minister Miri Regev follow on the heels of 2011’s “Nakba law,” which enables the withholding of funds to public institutions deemed to be involved in challenging the founding of Israel or any activity “denying the existence of Israel as a Jewish and democratic state.” This draconian law appears to have provided a template for the UK government to start censoring cultural voices in Britain that critique the state of Israel.

This development came to light in August 2014, when London’s Tricycle Theater refused to host the UK Jewish Film Festival (UKJFF) while it was partially funded by the Israeli embassy – a response to the loss of life resulting from Israel’s bombardment of Gaza. Although the Tricycle offered to provide alternative funding to cover the cost of the contribution from the Israeli embassy, the UKJFF was unwilling to decline embassy sponsorship and withdrew its festival from the theater.

The Tricycle came under sustained attack and was soon subject to an intervention from the then secretary of state for culture, Sajid Javid. Together with the minister for culture and the digital economy, Ed Vaizey, Javid worked closely with the Israeli ambassador at the time, Daniel Taub, to pressure the Tricycle to withdraw its objections to Israeli embassy funds. Unable to stand fast against threats to its own funding, the small venue withdrew its objection and invited the UKJFF back on the same terms as the previous year.

While attending an event organized by the Board of Deputies of British Jews in 2015, Javid noted that his intervention the year before was also intended to deter other organizations from exercising their right to boycott. “I have made it absolutely clear what might happen to [the theater’s] funding if they try, or if anyone tries, that kind of thing again,” he said.

Javid’s message rang loud and clear: Any boycott of Israel by British cultural institutions is out of bounds if they wish to receive funding. Israel’s policies and practices are no longer simply being ignored by UK ministers; now they are being adopted.

The Tricycle’s stance, while short-lived, nevertheless marked the beginning of a public debate about threats from pro-Israel government advocates to the independence of cultural institutions in the UK. In October 2014, a public discussion entitled “After the Tricycle: Can Arts Organizations Say ‘No’ to Embassy Funding?” was held at Amnesty International Action Center. During the discussion the need for effective strategies to contest political pressure on the arts became more apparent as other instances of institutional censorship and manipulation were reported.

One example cited was the April 2014 decision by the Donmar Warehouse, a theater located in London’s West End, to censor a podcast that was part of a discussion series that accompanied Peter Gill’s production of “Versailles.” Entitled “Impossible Conversations,” the series featured leading political and cultural commentators exploring the legacy of World War I. Twenty-four hours prior to one of the discussions – “Mr. Balfour’s Letter to Lord Rothschild: How the Great War Remapped the World” – the Donmar Warehouse received a complaint from a funder claiming that the event was an attack on the state of Israel, an anti-Israel rally, and anti-Semitic. Threats to withdraw funding accompanied the complaint, as well as a pledge to raise grievances with publicly funded cultural institutions at which the event’s programmer worked or served as a trustee. Although the Donmar Warehouse held the discussion, it chose not to post the podcast online along with the other discussions that took place.

Institutional and government censorship in support of Israel has also entered the academic sphere. In 2015, Eric Pickles, then secretary of state for communities and local government, ensured the cancellation of an academic conference on the legal status of the state of Israel at the University of Southampton. The conference included both an Israeli law professor and a Palestinian human rights activist, but Pickles claimed that the event would give voice to “the far-left’s bashing of Israel, which often descends into anti-Semitism,” rather than offer “a platform to all sides of the debate.” Michael Gove, then chief whip, joined the fray, declaring that “[i]t was not a conference, it was an anti-Israel hate-fest.”

In response to the government’s intervention, the university withdrew permission for the conference to be held on its property on health and safety grounds. The university claimed that the event could give rise to protests and that it did not have the resources to mitigate this risk, despite a statement from the police confirming they could ensure the security of the event. In April 2016, the conference was blocked for a second year when organizers were not able to pay the £24,000 ($29,000) the university required of them to cover the cost of hiring private security and erecting fencing.

Britain’s increasing involvement in the cultural repression of Palestinians is also occurring through the denial of UK visas. Arts, culture, and education help create spaces in which difficult problems can be addressed creatively – especially when people from different backgrounds and contexts are brought together in them. This is why cultural and educational exchanges between Palestinian and international artists and academics have been blocked by Israel’s occupation regime for decades. Most recently, Israel banned UK academic Dr. Adam Hanieh from entering Israel or Palestine for 10 years after he attempted to travel to Birzeit University to deliver a series of lectures. Israel also refused entry to the UK-based Palestinian writer Ahmed Masoud to participate in the Palestinian Festival of Literature in the West Bank earlier this year.

Lately, an increasing number of reports have also emerged regarding the denial of visas by UK authorities to Palestinian artists and academics seeking to come to Britain to participate in exhibitions, theater productions, speaking tours, and conferences. Hamde Abu Rahma, a Palestinian photojournalist, was twice denied a UK visa despite financial backing and support from a number of British MPs before he was finally granted permission to come to Scotland for this year’s Edinburgh Festival. Other Palestinian artists whose denied visas have been made public in recent years include Ali Abukhattab and Samah al-Sheikh, writers who were due to appear at the Institute of Contemporary Arts as part of the Shubbak festival, and Nabil al-Raee, artistic director of the Jenin Freedom Theater who was supposed to speak at a number of UK events. The UK visa system is also becoming more of an obstacle to developing academic partnerships with Palestinian universities. Because it is extremely difficult to obtain clear information about the visa process, institutions’ ability to work collaboratively is hindered. Palestinian academics and students alike are being denied entry. According to the British Council, this year for the first time five out of ten of their sponsored Palestinian students were refused visas.

Arts and education organizations have largely been dealing with such access issues individually, in the hope of reaching a solution by working quietly with the UK authorities on a case-by-case basis. Israeli artists and academics, however, are not subject to the same restrictions, even if they come from illegal settlements in the West Bank. While an Israeli settler can simply obtain a visa on arrival in the UK, a Palestinian living down the road must go through an expensive and complicated application process before they travel, with dwindling hopes of success.

It is essential that British institutions are not discouraged from inviting Palestinians to participate in their activities, especially while the UK government cracks down on the cultural boycott and stifles academic debate under the guise of ensuring a platform for “all sides.”

Promoting Palestinian Cultural Production

Changing attitudes and practices in the UK toward Palestinian culture and identity, which have been relegated to an inferior role ever since the days of Balfour, is no easy task. There is, however, much that Palestinian civil society and solidarity groups are doing, and can do more of, in the run-up to the centenary of the Balfour Declaration to create conditions to put an end to British complicity in the censorship of Palestinians and to the UK government’s prejudicial policies in support of Israel.

Organized public pressure is a key element in creating such conditions. The Palestinian poet Dareen Tatour’s imprisonment has received increasing international attention and the support of over 250 renowned writers, poets, translators, editors, artists, public intellectuals, and cultural workers. Tatour believes this international response could influence the final outcome of her case. “Public pressure,” she says, “may force the Israeli authorities to reconsider the persecution of Palestinian artists, writers, and young activists just because they express their rejection of oppression.” As such, Palestinian civil society and solidarity groups can work jointly to increase international pressure for the release of Tatour and work to intensify the Stop G4S campaign in solidarity with all Palestinian political prisoners.

More generally, these groups can also:

Nearly 100 years after Balfour, one thing is certain: It is time for Britain to adopt a new approach. The centenary presents an opportunity for the UK not only to cease aiding Israel in its bid to silence Palestinians and stonewall cultural exchange, but to actively promote Palestinian cultural production and ensure that Palestinian stories are being told.

An extremely well-coordinated campaign is required, however, to ensure that sufficient public pressure is put on the UK government to finally acknowledge the devastating impact of its historic intervention and begin to make reparations for its past and present complicity in the cultural repression and ongoing dispossession of Palestinians.

Aimee Shalan

Latest Analysis

The NCAG: Gaza’s Technocratic Turn to Genocide Management

De-Healthification: Israel’s Engineered Collapse of Palestinian Life

The World Radicalized by the Gaza Genocide

We’re building a network for liberation.

As the only global Palestinian think tank, we’re working hard to respond to rapid developments affecting Palestinians, while remaining committed to shedding light on issues that may otherwise be overlooked.