Two decades after the Oslo Accords, the Palestinian leadership has failed to bring about peace, justice, and self-determination to the Palestinian people. Indeed, failure of leadership has marked the Palestinian struggle for the past century and was marked during the British Mandate and the 1936-39 uprising. With the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Palestinian Authority (PA) facing a legitimacy crisis, Al-Shabaka convened this Leadership and Accountability Policy Circle to focus on what can and should be done to ensure a Palestinian leadership that fully represents Palestinians, restores their unity, and respects their rights while they struggle for freedom.1

An Al-Shabaka policy circle is a specific tool used to engage a group of analysts in longer-term study and reflection on an issue of key importance to the Palestinian people. In our policy circle methodology, the participants hail from different parts of the world and can pull in other expertise from within or outside the Al-Shabaka network as needed. Members of the policy circle will also, together or on their own, produce policy briefs and commentaries among other Al-Shabaka analysis.

Marwa Fatafta and Alaa Tartir are the co-facilitators of this Policy Circle, which kicked off with a brainstorming of ideas by the participants on these three questions: What governance model could ensure the full democratic representation and popular participation of the Palestinian people within and outside the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT)? How can we ensure that a new leadership and institutions are accountable to and meet the needs of the Palestinian people? How can we overcome the geographical and political fragmentation of Palestinians?

While the analysts’ views vary, all begin from the premise that the Palestinian leadership – which many Palestinians consider corrupt, outdated, and/or serving only to suppress the Palestinian people’s quest for rights – must at the very least be restructured.

Dana El Kurd advocates for a return to the original PLO structure whereby the Palestinian diaspora would play a key role in refocusing the direction of the Palestinian people. Marwa Fatafta and Inès Abdel Razek propose broader changes, calling for the decentralization of the PLO and PA to give more authority at the local level and break up the current leadership’s power monopoly. While Fatafta outlines the challenges that would hinder such a process, Abdel Razek envisions its future workings. Tareq Baconi and Ali Abdel-Wahab recommend the formation of a committee or body outside the current leadership to bring about a new representative model. For Abdel-Wahab, this would pave the way for a populist democracy led by civil society institutions. In a longer analysis produced as part of this policy circle but published separately, Fadi Quran traces the different styles, eras, mechanisms, and transitions of Palestinian leadership across the past century and draws lessons for the future. To read his contribution, see here.

Dana El Kurd

Up to 1994, the PLO served a dual purpose: a government in exile linking Palestinians across the diaspora, and a military force dedicated to resisting the Zionist project. Over time, Israeli aggression pushed the PLO and its leadership to consolidate and centralize power and give more attention to the body’s military purpose than to governance. In the wake of the Oslo Accords and, later on, the split between the PA and Hamas, each has developed its own form of “governance” and armed structures, with those reporting to the PA essentially engaged in maintaining Israeli dominance over the Palestinian territories. Nevertheless, the PLO structure in its original form provides opportunity for democratic representation and participation.

The PLO serves as an umbrella organization consisting of the Central Council, the Executive Committee, and the Palestinian National Council (PNC). The PNC is the legislative body intended to represent Palestinians in historic Palestine and abroad. The PNC holds the most authority and responsibility, and its members are largely elected in addition to being incorporated from the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. In theory, the PNC acts as a check on the power of the executive. The Central Council incorporates membership from all branches of the PLO structure, and is intended to function as an intermediary between the PNC and Executive Committee when the PNC is not in session.

As such, the institutions and mechanisms by which Palestinians can hold their leadership accountable and be involved in decision-making already exist. Instead of reinventing the wheel, Palestinian society at home and abroad should demand a return to the PLO’s original structure. This would include reactivating the PNC through a call for new elections in the diaspora and at home via the PLC.

Of course, the geographic and political fragmentation of Palestinians poses a serious challenge to any such plan. To ensure political representation, all relevant groups in Palestinian society must be incorporated under the PLO’s umbrella, including Islamist groups.

The institutions and mechanisms by which Palestinians can hold their leadership accountable and be involved in decision-making already exist Share on XIn theory, PNC members would be accountable to the constituencies they represent. For example, PNC members from the US would answer to the Palestinian community who elected them. To ensure an added measure of accountability, new elections could also introduce the possibility of recalls on any PNC member by their constituency.

Moreover, while the PLO functioned with an elected PNC during a time with no internet, social media, or large-scale connectivity, technological advancements can now help alleviate geographic fragmentation. Many countries have experimented with “digital” or “e-democracy” or “e-government” in recent years, such as Iceland, which amended its constitution via online participation, and Brazil, which has implemented the “e-democracia” system whereby Brazilians take part in parliamentary debate and regularly interact with their representatives. The talents of dedicated Palestinian activists could be put to good use, initiating a registration campaign for the Palestinian diaspora and then holding elections – all facilitated by these new technological advancements and informed by past e-democracy experiences.

It is important to address the legitimate complaint against elections in an environment of occupation and continued ethnic cleansing. Many argue that elections in such a context only serve to distract Palestinian society by prompting it to squabble over seats rather than face the common threat of Israeli aggression. This complaint is relevant only when it comes to PLC elections, whose leadership is torn over who will control the few shreds of territory that are left. Such internal divisions should not be the case when it comes to the PNC and the broader PLO. Reactivating PLO institutions and electing a legislative body to represent Palestinians around the world is a necessary step in incorporating the full demands of Palestinians in any future negotiation.

Creating new institutions from the ground up in a fragmented and increasingly polarized environment might very well be impossible. It is therefore important to utilize the institutions Palestinians already have available and attempt to reform them rather than dispose of them altogether.

Marwa Fatafta

The traditional Palestinian leadership model is a centralized patrimonial form of power. The power structure of intra-Palestinian politics has always revolved around one political figure or faction, such as Yasser Arafat or Fatah, aided and supported by a network of clienteles and benefactors. The consolidation of power in the hands of one central political actor has not only led existing Palestinian institutions to fail to act democratically on behalf of the Palestinian people, but has also led to the marginalization and deliberate exclusion of other Palestinian political actors and factions perceived as rivals. It has also created a wide gap between the current Palestinian leadership and the elite that supports it and the rest of the Palestinian populace.

The domination of Fatah over the PLO and later over the PA, for example, has led to the systematic alienation and downsizing of other Palestinian voices and has reduced the function of institutions to serve the interests of Fatah rather than the interests of the Palestinian people at large.

To remedy this consolidation of power, decentralization of governance is needed in which the focus is on Palestinian grassroots localities and communities within the OPT and in the diaspora. Furthermore, the current Palestinian governance system is rife with corruption and abuse of power, with no accountability to the Palestinian people. Being able to hold a government to account is a prerequisite for any functional democratic governance system. Therefore, a vertical line of accountability must run through these localities to the PLO through such mechanisms as a functioning legislative body and free, fair, and regular elections. However, these forms of vertical accountability cannot stand alone. Systems of horizontal, internal accountability are also needed to ensure that Palestinian institutions function in full transparency and without corruption and abuse of power. As it stands, the lack of separation of powers within the current Palestinian leadership model urgently needs rectification.

The lack of separation of powers within the current Palestinian leadership model urgently needs rectification Share on XPalestinian President Mahmoud Abbas acts as the head of the PLO, the head of the PA, and the head of his political party, Fatah. He also holds legislative power in the absence of a functioning PLC. The president singlehandedly makes political decisions on the present and future of all Palestinians; this has catastrophic effects on the Palestinian cause and the direction it is heading. The PLO must encompass all Palestinian factions and cease the monopoly by Fatah.

Further, the factional hold the PA has on the PLO could be ended by separating the chairmanship of the two institutions. One proposal is to have the Palestinian president chair the PLO while the PA, led by a prime minister, be accountable to a legislative body at the PLO. The role of the PA must also be changed from a de facto legislative and executive power to a technocratic body that would provide basic services to and administer the day-to-day affairs of the Palestinian people living in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Change will be difficult under the ongoing military occupation, the political division between Fatah and Hamas, and the Palestinian elite’s corrupt grip on power. Four main challenges particularly hamper the establishment of a new model of democratic and accountable Palestinian leadership. The first is the Palestinian leadership and its clientele networks’ resistance to reform that would strip political and economic privileges from those in power. Institutional political change requires serious political will and commitment; otherwise, Palestinians are effectively replicating the experiences of neighboring Arab countries, whose corrupt bodies of governance manage to produce new heads that are more brutal than the last. In other words, what is needed is real institutional change rather than a focus on Abbas’s replacement – a question the international community often discusses.

A second challenge is external opposition to any change in leadership. The international community, for example, rejected the election of Hamas to the PLC in 2006 despite evidence that the elections were free, fair, and represented the will of the Palestinian people. This clearly shows that Palestinian leadership is not a solely Palestinian affair, but is susceptible to external intervention. Third, the political apathy of Palestinians and their disenfranchisement from the political process must be addressed. How can Palestinians revive trust and, most importantly, spur Palestinians to engage with a new or reformed body despite disappointment with past Palestinian leadership? The fourth challenge could emerge from technical difficulties brought on by the geographical fragmentation of the Palestinian people. Using technological and innovative digital tools is one possible means of overcoming territorial fragmentation, especially in the context of elections, but it brings with it a set of challenges. such as Palestinians’ access to the internet and technology worldwide and the risk of manipulating digital voting results.

Inès Abdel Razek

The current state of the international community and Israeli leadership, as well as internal Palestinian politics, have stifled any Palestinian leader or political force that could suggest a viable mid- to long-term vision and strategy for national liberation.

The current cast of Palestinian leaders was active in the liberation movement from the 1960s to the 1990s, and their mentality for liberation and the shape of their struggle are stagnant. Some of them are opposed to change altogether. This outdated leadership must give way to the younger generation to create a fissure in what has for too long remained concentrated power, currently held by PA and PLO figures. Capable Palestinians with sound policy-oriented and political ideas and visions are among us, but they are fragmented and cannot find space in the current PLO.

Full democratic representation of Palestinians must be ensured to override this consolidated power structure, and this can be accomplished through decentralization and localism as well as reform of the PLO structure. Decentralization is necessary given the territorial fragmentation of Palestinians, while a delegation of powers and finances to local levels would dissipate the monopoly on power. In the hypothetical case of a one-state solution, there should be a highly decentralized federal model consisting of autonomous governorates or districts.

Focusing on the local is important given that local elections have been the only elections held in the past 12 years. Palestinians also identify culturally and socially with their cities or geographical regions, predisposing communities to localism. Beyond elections, there is a need for forums where all local representatives meet on a regular basis to address the often-competing interests among localities and to ensure territorial cohesion.

The Palestinians need a system of strong, national political leadership that embraces decentralization Share on XBasic public services for Palestinians such as water and primary education should also be managed locally, with strategic spearheading from the center. Years of mistrust in the PA and its poor provision of public services due to privatization have eroded civic engagement. Placing the management of vital resources directly into the hands of local communities could cultivate a sense of ownership and civic duty, as well as foster more accountability on the part of the management. Direct citizen engagement with resources may also increase the will to pay taxes, currently dulled due to corruption and privatization.

Central leadership, however, is still important. Palestinians have always sought inspiring figures to defend their rights and aspirations with integrity. As such, the need is for a hybrid political and institutional system of strong, national political leadership with a clear strategic direction that embraces decentralization.

Palestinians should also have a functioning and empowered legislative body, representing all political parties and factions. This body should be renewed every four to five years through a universal vote. In the case of a one-state solution, all people should have the right to fair representation based on sound organization of districts or localities. Palestinian refugees and those in the diaspora should also be represented. Such a system can only happen with a restructuring of the PLO as well as transformation of the PA, which is merely a semi-government created by the Oslo Accords that has hindered building further Palestinian sovereignty.

The new model should also take demographic diversity into consideration, particularly regarding women and youth. The under-representation of these groups has reached dramatic lows despite access to high levels of education. When the average age at the PLO Central Council is no less than 65 years old, how can such an assembly bring an innovative and leading vision for the future? The introduction of quotas for women and youth in decision-making structures, political parties, and private sector boards would be one practical step.

Counter-powers are also a key element of a functioning democratic system in Palestine as well as worldwide. Laws and public spaces should ensure full respect for the human rights and public and political freedoms of citizens, and must not exclude journalists and activists. For instance, the media and online content must be diversified and professionalized in order to position and anchor Palestine in the region and the world through its own narrative, while giving a voice to people beyond the “usual suspects” of the economic, political, and social spheres. Professionalizing and empowering independent television channels and written media would be a start. Children and youth should also be encouraged to read, be intellectually curious, and to doubt and criticize, and the school system must teach them how to filter online information. Enabling rather than force-feeding and imposing these skill sets will prepare the next generation of Palestinians to participate in a vibrant democracy.

Tareq Baconi

Whether reformed or newly established, representative Palestinian institutions should be based on a model that accounts for the geographic fragmentation of the Palestinian people and the diversity of their localized struggles. Palestinian society could achieve such representation through some form of local census or elections that occur across Palestinian constituencies. A PLO leadership looking to revive the Palestinian National Council into a genuinely representative body could put forth an initiative to implement this process. An alternative innovative medium such as digital voting is also a potential option; this approach should be coupled with assistance to Palestinians without access to virtual platforms from grassroots civil society organizations.

Palestinian institutions should account for Palestinians’ geographic fragmentation and the diversity of their localized struggles Share on XBefore such a step can be taken, Palestinians must determine whether representative leadership should build on existing institutions or create an alternative to supplant existing leadership. Depending on the path chosen, the challenges will vary. But for both options, accountability and legitimacy will be one of the greatest issues that the initiative leaders will face. How do we ensure wide-reaching buy-in into this process if a “national” body does not push forward the effort?

One way to overcome such challenges would be to create a credible committee, severed from existing corrupt and illegitimate leadership institutions, to oversee this initiative. The committee would have to be representative and composed of members who have clear endorsement from their local communities. Once this committee is established, the process of facilitating valid representation into the Palestinian political establishment could begin. It is only through such a process, driven from the bottom up, that a true representative Palestinian leadership can be formed.

Ali Abdel-Wahab

In 2015, The Economist Intelligence Unit concluded that Palestine has a “hybrid” system, specifically an amalgamation of an authoritarian and semi-democratic regime. However, the best model for Palestinians would be popular or populist democracy, represented by civil society organizations. The creation of major civil society networks would properly forge access, association, and political mobilization of Palestinians. This model would provide the opportunity for true democratic thinking and genuine decision-making.

A populist democracy would provide Palestinians the opportunity for true democratic thinking and genuine decision-making Share on XCurrent and past models of democracy based on Palestinian political parties’ and the PA’s approach are all tainted by the Israeli occupation, internal Palestinian divisions, personalization, and political corruption. In order for a populist democratic model to succeed, Palestinians would need, in addition to civil society networks, an auditing body to monitor authority and ensure accountability. This body would gradually integrate representative interests and values into the design of policies.

The populist model for Palestinians faces many challenges, including geographical fragmentation and the lack of a collective political awareness among the Palestinian people due to a spreading culture of fear and submission. Palestinian civil society institutions must therefore put forward a focused roadmap based on real democratization and the consolidation of cultural, political, and democratic values. The incumbent regime, political parties, and intellectuals should take a backseat in the development of these plans, which must advance political participation as a culture and a system.

- Al-Shabaka publishes all its content in both English and Arabic (see Arabic text here). To read this piece in French, please click here. Al-Shabaka is grateful for the efforts by human rights advocates to translate its pieces, but is not responsible for any change in meaning.

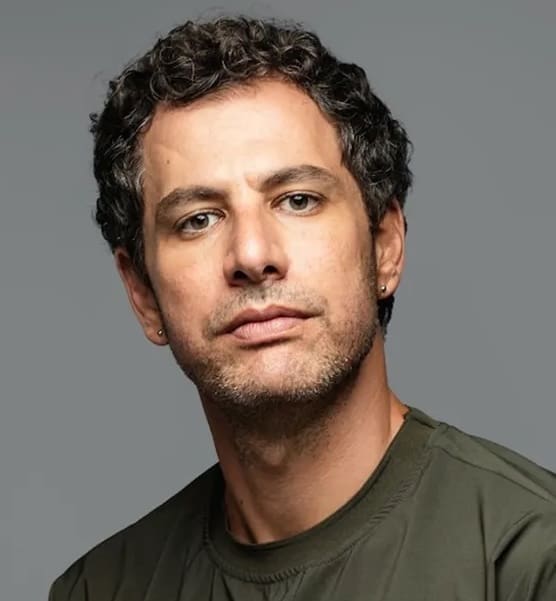

Marwa is a Palestinian writer, researcher and policy analyst based in Berlin. She leads Access Now’s work on digital rights in the Middle East and North Africa region as the MENA Policy Manager. She is also an advisory board member of the Palestinian digital rights organization 7amleh. Previously, she worked as the MENA Regional Advisor for Transparency International Secretariat. Marwa was a Fulbright scholar to the US, and holds an MA in International Relations from Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University. She holds a second MA in Development and Governance from University of Duisburg-Essen.

Tareq Baconi serves as the president of the board of Al-Shabaka. He was Al-Shabaka’s US Policy Fellow from 2016 – 2017. Tareq is the former senior analyst for Israel/Palestine and Economics of Conflict at the International Crisis Group, based in Ramallah, and the author of Hamas Contained: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance (Stanford University Press, 2018). Tareq’s writing has appeared in the London Review of Books, the New York Review of Books, the Washington Post, among others, and he is a frequent commentator in regional and international media. He is the book review editor for the Journal of Palestine Studies.

Inès Abdel Razek is the Executive Director of the Palestine Institute for Public Diplomacy (PIPD) and its digital platform Rabet, an independent Palestinian organization focusing on international mobilization and digital campaigning for Justice, Freedom and Equality. From 2019 to 2022, Inès was the Advocacy Director of the PIPD, helping to develop the political networks and international advocacy pillar of the organization. Prior to joining the PIPD, Inès held policy advisor positions in the Union for the Mediterranean in Barcelona, the UN Environment Programme in Nairobi and the Palestinian Prime Minister’s Office in Ramallah, where she advised executive leadership on international aid for development policies. Inès is also a board member of the social enterprise BuildPalestine, Advisory board member of Palestine DeepDive, and policy member at Al-Shabaka, the Palestinian Policy Network. She holds a Master’s degree in Public Affairs from Sciences-Po, Paris. Twitter: @InesAbdelrazek

Al-Shabaka Member Dana El Kurd received her PhD in Government from The University of Texas at Austin. She specializes in Comparative Politics and International Relations. Her dissertation explores how international patrons affect authoritarian consolidation in the Palestinian territories. Dana writes regularly for publications such as Al-Araby al-Jadeed, The Washington Post’s Monkey Cage blog, and Foreign Affairs. She currently works as a researcher at the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies and its sister institution, the Doha Institute for Graduate Studies.

Ali Abdel-Wahab is a data analyst and policy researcher with over 7 years of experience in Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability, and Learning (MEAL) within the humanitarian sector. He holds a bachelor’s degree in computer science and is keenly interested in big data and computational social sciences. Ali aims to leverage these tools in his research on political economy, digital transformation, network society, and technological and informational dominance, particularly concerning Palestine. He has published numerous articles and academic papers and is committed to developing innovative solutions to support decision-making and effective policy management.