Overview

In an unusual move, and after years of neglect, American and European delegations and development agencies have recently been visiting East Jerusalem and showing an increased interest in “doing something” about its deteriorating socioeconomic conditions. Moreover, the Palestinian Authority (PA) is, after a prolonged silence, working on updating the Strategic Multi-Sector Development Plan for East Jerusalem 2011-2013.12There are fears that the election of Donald Trump might put a damper on these welcome and long overdue initiatives. It is also problematic that these delegations focus on economic development when the reality is that real economic development is not possible without progress on the political front to free the Occupied Palestinian Territory and fulfill Palestinian rights in the context of a just and comprehensive peace.

This brief by Al-Shabaka Policy Fellow Nur Arafeh focuses on Israel’s deliberately engineered economic collapse of East Jerusalem, which renders the city essentially unlivable for Palestinians so as to ensure Jewish control over it. By so doing, the brief aims to provide those concerned with the fate of the city with the analysis necessary to understand Israel’s aims as well as some of the policy prescriptions to spur economic development. The brief zeroes in on the deterioration of two sectors that have been East Jerusalem’s prime strategic assets—tourism and the commercial markets of the Old City—which exemplify the economic collapse. It also explores initiatives undertaken in East Jerusalem to foster sumud, or steadfastness, that challenge the myriad obstacles imposed by Israeli occupation authorities and concludes with recommendations on how to enhance sumud in the city and restore its capacity for the limited economic development possible under occupation.

A Besieged Tourism Sector

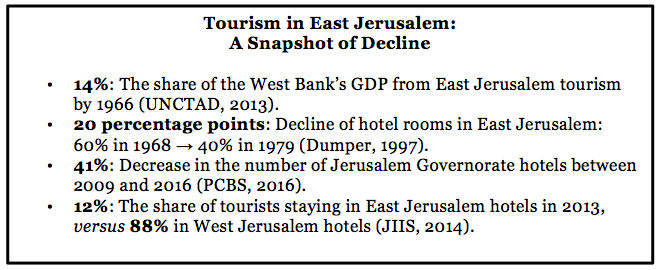

East Jerusalem has been a major tourist destination for decades. After 1948, when the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, came under Jordanian jurisdiction, tourism was the strongest sector in East Jerusalem’s economy. By 1966, it comprised 14 percent of the West Bank’s GDP and generated many jobs, thus increasing income and improving living standards. This led to a rise in government and private investment in physical infrastructure and tourism-related facilities. Tourism-related services were well developed by 1967 in comparison to other services.However, following the Israeli occupation and illegal annexation of East Jerusalem in 1967, the tourism sector began to stagnate. For example, there was a radical change in the distribution of hotel rooms between the western and eastern parts of the city. Between 1968 and 1979, the percentage of hotel rooms located in East Jerusalem declined from 60 percent to 40 percent. While there was a 20 percent increase in income for the East Jerusalem tourism sector between 1969 and 1973, the Israeli sector witnessed an 80 percent rise over the same period. By the mid-1980s, 80 percent of tourist bookings were in the Israeli sector.3

Israeli punitive measures during the first and second Intifadas, such as curfews and tax raids, further hampered the development of East Jerusalem’s tourism sector. Moreover, Israel’s construction of the Wall in 2002 and its subsequent intensification of restrictions on East Jerusalem’s development particularly damaged the sector, because such actions isolated the city from the rest of the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT). Obstacles have included cumbersome licensing procedures for constructing hotels or converting buildings to hotels; high municipal taxes; weak physical and economic infrastructure; and scarcity of land. Moreover, while the development of the Israeli tourism industry enjoys considerable government support, the Palestinian tourism sector is largely run by insufficient private investments and lacks meaningful support from the PA.The number of active hotels in East Jerusalem has thus been in decline. Between 2009 and 2016, the number of hotels in the Jerusalem Governorate decreased by 41 percent, from 34 hotels in 2009 to 20 during the second quarter of 2016.4 Recently, some hotels have been converted into offices, such as the Mount Scopus hotel, while the Al-Makassed hospital purchased the Alcazar hotel in Wadi El-Joz. Further, while 34 percent of hotels in the OPT were located in East Jerusalem in 2009, less than 18 percent of OPT hotels were in East Jerusalem by June 2016. The percentage of guests visiting the OPT and staying in East Jerusalem hotels has also declined from 48 percent in 2009 to 23 percent in the first half of 2016.The stifled development of the Palestinian tourism industry, combined with the negative perceptions of travel to Palestinian areas (mainly propagated by Israel), has led an increasing number of tourists to stay in West Jerusalem hotels. According to the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 88 percent of tourists chose hotels in West Jerusalem in 2013, while only 12 percent stayed in hotels in East Jerusalem. West Jerusalem hotels thus accrued 90 percent of hotel revenues in the same year.5Other factors that have weakened the tourism sector in East Jerusalem include the seasonality of Christian and Muslim pilgrimages, which are the main sources of business in the city; the heightened competition between tourism businesses due to their geographic concentration; political instability; a weak competitive advantage; the lack of a unique Palestinian tourism product; and an absence of a clear Palestinian vision and promotional strategy for the Palestinian tourism industry.

The Suffocation of the Old City Economy

The Old City of Jerusalem was a strong part of East Jerusalem’s economy, attracting Arab and Palestinian customers as well as tourists. Its present recession serves as a potent example of the economic marginalization that has weakened the economy and rendered life in East Jerusalem increasingly difficult for Palestinians.6The recession of the commercial markets in the Old City has been closely linked to the deterioration of the tourism sector in East Jerusalem. In the 1970s and 1980s, business activities in the Old City became increasingly reliant on tourism with the surge in the number of visitors. With this shift also came a change in the nature of the markets: While the Old City was known for its traditional industries and markets – for instance, the Souq al-’Attareen (spices), the Souq al-Lahameen (meat), and the Souq al-Qattanin (cotton) – it slowly lost these niche markets as merchants turned their businesses into souvenir shops as this was a more successful venture at the time. The ensuing economic marginalization of East Jerusalem and the decline in tourism businesses helped fuel the decline of commercial activities in the Old City.This situation was compounded further by the heavy taxes imposed by Israeli authorities to stifle Palestinian business activity. Palestinian merchants are required to pay six taxes: arnona, or property tax, value added tax, income tax, national insurance, payroll tax, and license tax. The inability of most Palestinian merchants to pay these taxes given the decline in their businesses has put many of them in debt. Israeli authorities have been offering merchants generous incentives to sell their stores if they cannot pay taxes, thus using taxation as a tool to confiscate Palestinian property and expand Jewish control over and colonization of the Old City. Moreover, in an effort to keep commodity prices low, Palestinian merchants have become increasingly dependent on importing foreign and Israeli goods. As a result, commercial markets in the Old City, which were known for the high quality of their goods, have become known for selling low-quality products.

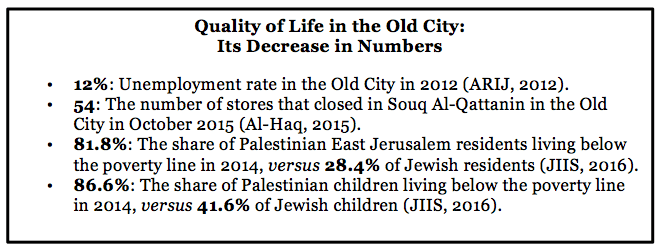

The subsequent loss of competitive advantage has been accompanied by the emergence of new business centers, such as Salah Al-Din, Shuafat, Beit Hanina, Al-Ram, and Ramallah, which have become easier to reach and thusmore attractive to Palestinians, especially after the construction of the Wall and the strict travel permit regime imposed by Israeli authorities. For instance, people living in Abu Dis either shop in Abu Dis or travel south to Bethlehem and Hebron, rather than going to East Jerusalem, because doing so would mean spending hours crossing Israeli-imposed checkpoints. According to a 2012 report by the Association for Civil Rights in Israel, “Only 4 percent of those living beyond the wall have continued to do their shopping in Jerusalem, whereas 18 percent did so before.”The combination of the new business centers, cumbersome tax burden, decline in the tourism sector, and weak purchasing power of Palestinians in East Jerusalem has suffocated the economy of the Old City. The unemployment rate in the Old City was 12 percent in 2012, with workers in tourism, trade, and industry the most affected. Further, according to the Jerusalem Arab Chamber of Commerce and Industry, more than 200 shops are currently closed in the Old City. Shops that are still open cannot stay open for longer hours at night because of their inability to cover operating costs. This has led to the “Jerusalem sleeps early” phenomenon whereby Jerusalem residents spend their evenings and weekends in Ramallah or Bethlehem instead of the city itself. The recent uprising has further exacerbated this situation, especially given Israel’s increased security measures. In early October 2015, Israel erected concrete roadblocks and checkpoints in several neighborhoods in Jerusalem as well as barriers inside and outside the Old City. According to a report by Al-Haq, Israeli authorities set up more than 30 checkpoints and observation points in the Old City that month, including four electronic detectors, severely constraining the movement of Palestinians and tourists. Palestinian merchants have also been subject to arbitrary punishments, such as arrests under the pretext that they did not assist Israelis who were attacked by Palestinians.The ensuing environment of fear among Palestinians and tourists has caused a further decline in the consumer base of the Old City, undermining business activity and leading many shops to shutter. According to the same Al-Haq report, 54 stores closed in Souq Al-Qattanin between October 1 and October 23. Other shops opened for only a few hours a day due to the lack of customers, and several Palestinian merchants sought employment in the Israeli labor market.Palestinian merchants have also been subject to fierce competition from Jewish Israeli merchants, especially as the latter have been receiving financial benefits from the Israeli government since the recent uprising. According to Palestinian merchants interviewed by the author, each Jewish merchant in the Old City received NIS 70,000 (more than $18,000) from the Jerusalem municipality and 50 percent breaks on the arnona tax, in addition to the financial support they already receive from Israeli organizations supporting illegal settlements in the OPT.7

Meanwhile, the High Committee for Jerusalem Affairs has planned to allocate $3,000 to each Palestinian merchant in the Old City – an amount the merchants consider too small to cover even part of their debts.8

Israel’s orchestration of the Old City’s economic recession, alongside its other policies such as house demolitions; a discriminatory provision of services, which sees Palestinian residents receiving fewer services but paying the same taxes as their Jewish counterparts; and the revocation of residency cards, purposefully render life increasingly difficult for Palestinians. This has gone hand in hand with Israel’s continued efforts to fast-track its colonization of East Jerusalem, including the Old City, by expanding its settlements.

“The economic marginalization of East Jerusalem and the decline in tourism businesses helped fuel the decline of commercial activities in the Old City.”

Settlement expansion is supported by right-wing organizations, such as Ateret Cohanim, within the heart of Palestinian neighborhoods, as they aim to create a Jewish majority in the Old City and in East Jerusalem at large. These organizations benefit from considerable assistance from the state, which provides private security services to protect settlers, especially during the expropriation of Palestinian properties. The state also funds development projects in the settlement enclaves and facilitates the transfer of Palestinian properties to right-wing organizations through bodies such as the Jewish National Fund and the Custodian of Absentee Property.Despite intensive settlement expansion Jews represent onlyaround 10 percent of the population of the Old City. Yet there has been an expansion in Jewish religious and educational institutions in the area.9

In particular, efforts have been made to encircle the Al-Aqsa compound inside and outside the Old City with Jewish sites in an attempt to Judaize the touristic landscape. Settlers’ main success has so far been the construction of the biblical theme park, “City of David,” which surrounds the Old City walls and encompasses most of the Wadi Hilwa neighborhood in Silwan to the south. The settler group El-Ad runs the park, which is one of the most visited tourist sites in Jerusalem. Israeli authorities and settlers use the park to project their desired image of Jerusalem as a “Jewish city” – which includes erasing the Palestinians’ physical presence and history.

The economic collapse of East Jerusalem, illustrated in this brief through a focus on tourism and the Old City’s commercial markets, has naturally led to deteriorating socioeconomic conditions for Palestinians. According to the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 81.8 percent of East Jerusalem residents and 86.6 percent of Palestinian children were living below the poverty line in 2014, compared with 28.4 percent of residents and 41.6 percent of children within the Jewish population.

The Strength of Sumud in East Jerusalem

Despite the economic obstacles it confronts, East Jerusalem remains at the forefront of Palestinian civil society’s strategies of sumud. These strategies focus on ensuring that Palestinians remain rooted to land under threat of confiscation; creating socioeconomic conditions that help Palestinians endure Israeli policies; maintaining the political identity and cultural heritage of the city; and promoting community-controlled development.10Several initiatives aim to preserve Palestinian presence in the Old City in the face of expanding settlements. For example, Burj al-Luqluq, a community center founded in 1991, was built in the Bab al-Hutta neighborhood on land that was under threat of expropriation to build a settlement. Other institutions work explicitly to preserve the cultural heritage and Palestinian tourism landscape of the Old City as Israel’s Judaization policies attempt to erase them. For example, the Welfare Association’s Restoration Program in the Old City focuses on the rehabilitation of housing units; the provision of cultural, social, commercial, and health services to improve Palestinians’ lives; and the restoration of historic, neglected buildings for community use. The Welfare Association, among other activities, converted a Byzantine building into the Al-Quds Community Work Center and a public khan into the Al-Quds University Studies Center. These efforts help to ensure an institutional Palestinian presence in the Old City and attract foreign tourists. Given the absence of governmental and international aid, bottom-up initiatives working to ensure the tourism sector’s survival have always been the norm in East Jerusalem. More recently, Palestinian tourism experts in East Jerusalem, such as the Jerusalem Tourism Cluster, have increased efforts to develop a new tourism paradigm with the goal of challenging the obstacles imposed by Israel on the sector’s development.11

The diversification of the tourism product is at the heart of this initiative. The idea is to build a unique Palestinian identity for the product while simultaneously developing new types of tourism that are not only about pilgrimage, such as tours that focus on politics, culture, ecology, and recreation. Such a shift could also overcome the seasonality of Palestine’s tourism business.

“Despite the economic obstacles it confronts, East Jerusalem remains at the forefront of Palestinian civil society’s strategies of sumud.”

There are also political tours of East Jerusalem organized by Alternative Tours, for example, which take visitors to the settlement of Pisgat Zeev in East Jerusalem, where they have a view of the Wall and the Shuafat refugee camp so that they become more informed about Israel’s illegal settlement policies.To ensure the sustainability of such tours, these initiatives seek to involve the Palestinian community beyond those Palestinians who serve as tour operators or otherwise work in the tourism sector. Future plans focus on developing community tours and tourism cooperatives that foster interactions between tourists and locals. These initiatives also encourage partnerships among sectors that are directly or indirectly linked to tourism, such as the commercial, cultural, religious, IT, and educational sectors.Dalia Association, a community foundation as well as a grant-making organization, also promotes community-controlled grant making and development to enhance the accountability of local initiatives and reduce dependency on donor aid. It has focused on mobilizing resources and connecting them to local and international Palestinian communities, based on the principle that each Palestinian community should identify its priorities and choose how to utilize resources. For instance, during the month of Ramadan in the summer of 2016, the association launched the “Jerusalem Fund” program, which focused on supporting Palestinian families whose houses had been demolished and empowering Jerusalem youth through the “Youth Empowerment, Youth Grantmaking” program. Donations were funneled through the fund, and a committee comprised of community residents decided how to allocate them so that they met local priorities.The Palestinian private sector and Palestinian banks have also recently started to invest in East Jerusalem. The Palestine Investment Fund announced in September that it would invest in developing a tourism infrastructure in East Jerusalem by renovating existing hotels and building new ones. Moreover, while banks in the OPT have not offered any housing loans to Palestinian residents in East Jerusalem since 1967, three banks lately decided to provide such loans from funds they received from the Islamic Development Bank.

Enhancing Sumud in East Jerusalem

While true economic and social development cannot occur without progress on the political front, developing sumud in East Jerusalem can shore up the Palestinian presence and improve Palestinians’ quality of life. Some suggestions and recommendations on how to enhance sumud in the city are made below.

- Envisioning Jerusalem Because initiatives undertaken in East Jerusalem are often fragmented and lack a clear national vision and strategy, it is vital for Palestinians to formulate a plan for Jerusalem by answering the question: “What kind of Jerusalem do we want to live in ten years from now, and what should we do to implement this vision?” Grassroots and community participation in the development of the vision can be ensured by establishing community-based partnerships or networks among East Jerusalem institutions. This would strengthen the institutional fabric and promote cooperation. Measures should also be established to ensure that all actors are held accountable for the implementation of strategies.

- Packaging Jerusalem The development of the tourism sector could be achieved by promoting domestic tourism and marketing East Jerusalem within a Palestinian package, such as one that consists of stops in Hebron, Bethlehem, Jericho, Jerusalem, Nablus, and Nazareth.12 Such work requires networking and partnerships among Palestinian tourist organizations from the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the ’48 region. Schools could also be involved in the development of domestic tourism by organizing visits to the Old City and other major tourist sites. These activities would help to develop economic links between the economy of East Jerusalem and the rest of the OPT.

East Jerusalem could also be marketed within a regional package, such as one that includes visits to Amman, Jarash, Petra, Aqaba, Jericho, and Jerusalem. In this way, tourists who are not only traveling for religious reasons would likely stay in East Jerusalem for a longer period, thereby increasing the city’s share of the tourism market and making it a cultural as well as religious destination.

“It is vital for Palestinians to answer the question, ‘What kind of Jerusalem do we want to live in ten years from now, and what should we do to implement this vision?'”

An Islamic tourism campaign could also be beneficial. The PA could work with Asian and African Islamic countries to organize pilgrimage tours to Jerusalem in cooperation with Jordan and Palestinian tour operators in Israel.However, to achieve the above, it is vital to develop a clear promotional strategy for East Jerusalem, ensure coordination among tour operators in the OPT and ’48 region, and develop a better tourism infrastructure in East Jerusalem by expanding the number of rooms in Palestinian hotels. It is also crucial to improve marketing through the use of digital and social media as well as participation in tourism fairs and conferences. Further, the managerial and technical expertise of those working in the tourism industry should be developed to ensure competitive service quality. The international community could play an important role in funding such efforts.

- Promoting Productivity The productive capacity of the economy of East Jerusalem must be rebuilt to enhance its competitive advantage. This can be done by exploiting its strategic asset – the Old City – and promoting the production of high-quality goods. Investments in small-scale industries, especially traditional handicrafts, would go a long way toward meeting this goal.

- A development fund for East Jerusalem should also be created that could serve different functions, including helping merchants in the Old City pay the exorbitant tax bill; financing social welfare programs; providing funds for schools to offset Israeli efforts to cut their funding if they do not use the Israeli-produced curriculum; promoting public and private investment in tourist facilities and housing projects for poor families; developing economic infrastructure; and buying properties for Palestinian institutions to overcome the financial difficulties associated with paying rents. The Palestinian private sector, Palestinian banks, and the Palestinian diaspora, among others, could help establish and finance such a fund.

In addition to the economic measures above, political measures are no less important. International delegations can play a major role by pressuring Israel to re-open Palestinian institutions such as the Industrial Chamber of Commerce and the Orient House, and by investing in the development of Palestinian tourism. Moreover, the international community has a responsibility to hold Israel accountable for its illegal occupation and annexation of East Jerusalem, and help build a new paradigm based on respect for international law and human rights.

- The author thanks the Heinrich-Böll-Foundation’s Palestine/Jordan Office for their partnership and collaboration with Al-Shabaka in Palestine. The views expressed in this policy brief are those of the author and therefore do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Heinrich-Böll-Foundation.

- Al-Shabaka publishes all its content in both English and Arabic (see Arabic text here.) To read this piece in French, please click here. Al-Shabaka is grateful for the efforts by human rights advocates to translate its pieces into French, but is not responsible for any change in meaning.

- These statistics are based on Michael Dumper, The Politics of East Jerusalem since 1967 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997).

- The Jerusalem Governorate as defined by the PA has different geographical and district boundaries than the Israeli municipal area of Jerusalem. For the PA, East Jerusalem is part of the Jerusalem Governorate, which includes areas J1 (the part of Jerusalem that was annexed by Israel in 1967) and J2 (the remainder of Jerusalem that is under Palestinian administration).

- There is a lack of official, reliable data on the tourism industry in East Jerusalem, save for that regarding the hotel business; hence such statistics are used here to assess the sector.

- This section draws on a study published in Arabic by the author and the Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS), titled “The Current State of the Markets in the Old City of Jerusalem,” July 27, 2016. The Arabic original can be accessed here.

- Quoted in the paper published by MAS, op cit.

- The High Committee for Jerusalem Affairs was established in 2005 and headed by Ahmad Qurei’, the then PA prime minister. It acts, with the PA and the Executive Committee of the Palestine Liberation Organization, as the main reference for all issues pertaining to Jerusalem.

- The percentage of Jews living in the Old City was calculated via statistics available in the 2015 diarypublished annually by the Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs.There were 3,350 Jews living in the Old City in 2015, compared with a total of 35,350 Muslims, Christians, and Armenians.

- UNDP publication, forthcoming.

- Interview with the author, May 20, 2016, East Jerusalem.

- Discussions at several workshops held by the Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs (PASSIA) in 2016 touched on this strategy, and a participant at an economic conference held by the Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute also recently proposed the idea.