Executive Summary

Jerusalem 2050: A largely-Jewish high-tech tourist destination with a minimal Palestinian presence. This is Israel’s vision of the city, and it is being implemented through three master plans – two of which are relatively unknown. Al-Shabaka Policy Fellow Nur Arafeh provides a succinct analysis of all three plans and the ways in which Palestinians can rebut them.

Key Points

- There are three Israeli master plans for the city of Jerusalem. The best known is the Jerusalem 2020 Master Plan, first published in 2004. The other two are below the radar: The Marom Plan, a government-commissioned plan, and the Jerusalem 5800 Plan (also known as Jerusalem 2050), the outcome of a private sector initiative.

- These master plans reinforce each other in their aim to maximize the number of Jews and reduce the number of Palestinians in Jerusalem through processes of colonization, displacement, and dispossession.

- The plans focus particularly on the development of tourism in the city, as well as of higher education and high tech. Urban planning and the enforcement of laws are some of the methods by which the plans work to ensure a Jewish majority and constrain the urban expansion of Palestinians.

- To rebut the colonization of Jerusalem, popular committees should be established in order to advocate for East Jerusalem residents’ rights and jointly serve as a representative body on a local and international level.

A Jewish Destination for Tourism, Higher Education, and High-Tech

The development of the tourism sector in Jerusalem is at the heart of the three development plans. Tourism is seen as an engine of economic development to attract Jews to the city, and is also a tool to control the narrative and ensure the projection of Jerusalem to the outside world as a “Jewish city.”

Plans to promote Israeli tourism have gone hand in hand with Israeli-imposed restrictions on the development of the Palestinian tourism industry in East Jerusalem. The Palestinian tourism sector is further hampered by the lack of a clear Palestinian vision and promotional strategy, which impedes its ability to fuel the limited economic development possible under occupation.

Another common goal of the three plans is to attract Jews from all over the world to Jerusalem through the development of higher education and high tech, including by building an international university in the city center. The plans aim to make Jerusalem a leading academic city that is attractive to both Jewish and international students, who will be encouraged to settle there once they have finished their studies. Another aim is to make Jerusalem a center of R&D in the field of biotechnology.

Evicting Palestinian Using Urban Planning and the “Law”

Measures to ensure a Jewish majority in Jerusalem and Israel’s de facto political borders of the city include the Separation Wall, urban planning, and the enforcement of laws.

Urban planning is a crucial element of the 2020 Master Plan. It encourages Jewish settlements in East Jerusalem and aims to reduce negative migration. While the plan recognizes the housing crisis suffered by Palestinians and makes recommendations to alleviate it, the recommendations are in fact discriminatory.

For example, 55.7% of additional housing for Palestinians will be through building within existing urbanized areas while 62.4% of Israeli Jewish building will be through expansion of urban areas. And while 9,500 dunums are planned for Israeli Jewish construction, only 2,300 dunums are planned for Palestinian construction. The plan also supports spatial segregation, that is, the division of Jerusalem into planning districts based on ethnic affiliation – in which no area would combine Palestinians and Israeli Jews.

Israel has also been using law as a tactic to evict Palestinians and appropriate their land. One of these laws is the Absentee Property Law, which enables Israel to confiscate the property of East Jerusalem Palestinians currently living in the West Bank by considering their property in East Jerusalem “absentee.” Another law is the Third Generation Law, which dictates that properties rented before 1968 by Palestinians must be returned to the original owners, who are mainly Jews who owned the property before 1948, upon the death of the third generation of Palestinian tenants.

Saving Jerusalem

To rebut the colonization of Jerusalem and the dispossession of its Palestinian population, there is broad agreement among representatives of Palestinian organizations, official bodies, and community groups that steps should be taken to establish popular committees in each East Jerusalem neighborhood.

These committees could raise residents’ awareness about their rights and about Israel’s plans for the future, and they could form a representative body for Jerusalem at the national level. The body would work as a channel between Palestinians in East Jerusalem and 1) the Palestinian Authority; 2) the Arab and international community; and 3) Palestinian communities in their homeland as well as in the diaspora.

Overview

It is the year 2050 and Israel has fulfilled its vision for Jerusalem: Visitors will see a largely Jewish high-tech center amid a sea of tourists, with a minimal Palestinian presence. To achieve this vision, Israel is working on three master plans; one is well-known but two remain under the radar.1 Edward Said had already warned in 1995 that “only by first projecting an idea of Jerusalem could Israel then proceed to the changes on the ground [which] would then correspond to the images and projections.” Israel’s “idea” of Jerusalem, as elaborated in its master plans, involves maximizing the number of Jews and reducing the number of Palestinians through a gradual process of colonization, displacement and dispossession (see Al-Shabaka policy brief on the methods used as well as this recent update).

The best known of the three Israeli master plans for the city is the Jerusalem 2020 Master Plan, which has not been deposited for public view even though it was first published in 2004. The least known are the Marom Plan, a government-commissioned plan for the development of Jerusalem, and the “Jerusalem 5800” Plan, also known as Jerusalem 2050, which is the outcome of a private sector initiative and is presented as a “transformational master plan for Jerusalem” (see below).As Israel plans for 2050, the Palestinian Authority (PA) “idea” of Jerusalem dates back to 2010 when the Strategic Multi-Sector Development Plan for East Jerusalem (SMDP) 2011-2013 was published. And the PA’s current national development plan for 2014-2016 simply refers back to the 2010 plan. In addition, while the Palestinian leadership speaks of East Jerusalem, which Israel occupied and illegally annexed in 1967, as the capital of the State of Palestine and a priority development zone, only 0.44% of the PA’s 2015 budget was to be allocated to the Ministry of Jerusalem Affairs and to the Jerusalem Governorate.

In this policy brief Al-Shabaka Policy Fellow Nur Arafeh analyzes all three Israeli master plans for Jerusalem, explaining how they aim to shape the city into a tourism and high-tech center, and the ways in which they use urban planning to reshape the city’s demography. She spotlights the dangerous new laws Israel has reactivated or passed to advance its colonization of the city – the Absentee Property Law and the “third generation law”. She also addresses the role of the PA and the international community as well as of civil society organizations, and identifies achievable measures that can be implemented by those concerned with Jerusalem’s fate.2

Before analyzing the ways in which the three plans reinforce each other, it should be noted that Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem is illegal under international law and is not recognized by the international community. In addition, Israel’s declaration that Jerusalem is its capital, both West and East, has no international legal standing, which is why there is no diplomatic representation in Jerusalem, not even by the United States.

- The “Jerusalem 2020 Master Plan” was prepared by a national planning committee and first published in August 2004. It is the first comprehensive and detailed spatial plan for both East and West Jerusalem since Israel’s occupation of East Jerusalem in 1967. Although the plan has not been validated yet as it was not deposited for public review, Israeli authorities are implementing its vision. The plan addresses several development areas including urban planning, archeology, tourism, economy, education, transportation, environment, culture, and art. The plan is available online in Hebrew as well as in Arabic at the Civic Coalition for Defending the Palestinians’ Rights in Jerusalem; this policy brief draws on the “Local Outline Plan”- Report N.4.

- The Marom Plan is a government-commissioned plan for the development of Jerusalem that will be implemented by the Jerusalem Development Authority. The Authority’s goal is to promote Jerusalem “as an international city, a leader in commerce and the quality of life in the public domain.” It is a major planning body for the Jerusalem Municipality, the land Administration, and other organizations in the fields of housing, employment, etc.

The Jerusalem Institute of Israeli Studies is conducting the consultation, research, and monitoring for the Marom Plan. The Institute is a multidisciplinary research center that plays a leading role in the planning and development policies for Jerusalem in the fields of urban planning, demography, infrastructure, education, housing, industry, labor market, tourism, culture, etc.

- The “Jerusalem 5800” Master Plan, also known as “Jerusalem 2050,” is a private initiative founded by Kevin Bermeister, an Australian technology innovator and real estate investor. The plan provides a vision and project proposals for Jerusalem up to the year 2050, serving as a “transformational master plan for Jerusalem” that can be implemented together with other municipal and national government agencies. It is divided into various independent projects, each of which can be implemented on its own. The team for the implementation of the plan is said to include “the best Israeli tourism, transport, environment, heritage and security planners.”

A Jewish Destination for Tourism, Higher Education and High-Tech

The development of the tourism sector in Jerusalem is at the heart of the three development plans examined in this policy brief. For example, under the 2020 Plan, the Jerusalem Municipality seeks to promote the tourism sector and to especially enhance the cultural aspects of Jerusalem. It is planning a marketing campaign to increase the potential of real estate development, support international and urban tourism, and invest in tourism infrastructure to ensure the sector’s development.The Marom Plan also aims to develop Jerusalem as a tourist city. In 2014 alone, the Jerusalem Institute of Israeli Studies conducted 14 of its 18 studies for that year on the tourism sector and submitted them to the Jerusalem Municipality, the Ministry of Jerusalem and Diaspora Affairs, and the Jerusalem Development Authority. Moreover, as part of the Marom Plan, the Israeli government earmarked around $42 million to boost Jerusalem as an international tourist destination, while the Ministry of Tourism was expected to allocate some $21.5 million for the construction of hotels in Jerusalem. The Authority also offers specific incentives to entrepreneurs and companies to establish or enlarge hotels in Jerusalem, and to organize cultural events to attract tourists such as the Jerusalem Opera Festival as well as events for the tourism industry, such as the Jerusalem Convention for International Tourism.Promoting the tourism sector also lies at the core of the Jerusalem 5800 Master Plan, which envisages Jerusalem as a “Global City, an important tourist, ecological, spiritual, and cultural world hub” that attracts 12 million tourists (10 million foreign and 2 million domestic) and more than 4 million residents. To make Jerusalem “the Middle East’s anchor tourist attraction and resource,” the Jerusalem 5800 plan aims to increase private investment and construction of hotels; build rooftop gardens and parks; and transform the areas surrounding the old city into hotels while prohibiting the use of vehicles. The plan also envisions the construction of high-quality transportation routes, including a “high-speed national rail line; an extensive network of buses and public transportation; the addition of numerous highways and the expansion of existing roads; and an express ‘super highway’ that transverses the country from north to south.” The plan also proposes the construction of an airport in the Horkania Valley between Jerusalem and the Dead Sea to serve 35 million passengers per year. The airport would be connected through access roads and rail to Jerusalem, Ben Gurion airport and other city centers.

Israeli Plans to Promote the Tourism Sector

$42 million: To boost Jerusalem as an international tourist destination (Marom Plan).

$21.5 million: For the construction of hotels in Jerusalem.

12 million tourists: Goal for annual visitors under the Jerusalem 5800 Master Plan

The Jerusalem 5800 plan attempts to present itself as an apolitical plan that promotes “peace through economic prosperity” but it has demographic goals that prove otherwise. In fact, it envisages that the $120 billion of total added value from the implementation of the plan, together with the 75,000 – 85,000 additional full time jobs in hotels plus 300,000 additional jobs in related industries would all reduce poverty – and would attract more Jews to Jerusalem, increasing the number of Jews living in Jerusalem and further tilting the Jewish-Palestinian demographic balance in their favor.However, the tourism sector is not only seen as an engine of economic development to attract Jews into the city. Israel’s development of, and domination over, the tourism sector in Jerusalem, is a tool to control the narrative and ensure the projection of Jerusalem in the outside world as a “Jewish city” (see for example the official Ministry of Tourism map of the Old City.) Israel has strict rules over who can serve as tour guides and the narrative and history that the tourists are told. Palestinian tour guides who do not abide by Israel’s false branding and who try to give an alternative and critical analysis of the situation can lose their licenses. These plans to promote the Israeli tourism industry have gone hand in hand with Israeli-imposed restrictions on the development of the Palestinian tourism industry in East Jerusalem. Israeli hurdles include: the isolation of East Jerusalem from the rest of the occupied Palestinian territory (OPT), especially after the construction of the Wall; shortage of land and the resulting high cost; weak physical infrastructure; high taxes; restrictions on the release of permits to build hotels or convert buildings to hotels; and difficult licensing procedures for Palestinian tourist businesses. These obstacles, even as millions of dollars are being poured into the Israeli tourism market, ensure that the Palestinian tourism industry has no hope of competing with Israel’s.The Palestinian tourism sector is further hampered by the lack of a clear Palestinian vision and promotional strategy, severely impeding its ability to fuel the limited economic development possible under occupation. Moreover, although civil society organizations have stepped in to promote the sector, their efforts have been described as “fragmented and poorly coordinated” in an analysis in This Week in Palestine. Another common goal of the three plans is to attract Jews from all over the world to Jerusalem by developing two advanced industries: Higher education and high tech. To promote the higher education industry, the 2020 Master Plan aims to build an international university in the city center with English as the main language of instruction. As for the Marom Plan, it seeks to make Jerusalem a “leading academic city” that is attractive to both Jewish and international students, who will be encouraged to settle in Jerusalem once they have finished their studies. In the same vein, the Jerusalem 5800 plan sees an opportunity to create jobs and achieve economic growth through “extended-stay educational tourism.”The development of the higher education industry is intrinsically linked to the development of a high-tech, bio-information, and biotechnology industry. The 2020 Master Plan calls for the establishment of a university for management and technology in the city center of Jerusalem, and for government assistance in Research and Development (R&D) in the fields of high-tech and biotechnology. Similarly, the Marom Plan aims at promoting Jerusalem as a center of R&D in the field of biotechnology. It is within this context that the Jerusalem Development Authority established the BioJerusalem Center to foster clusters of bio-med companies in Jerusalem as a potential engine of economic development. To attract these companies to Jerusalem, the Authority is offering very generous benefits including: Tax breaks, grants for hiring new workers in Jerusalem, and special grants to companies involved in R&D or in building physical infrastructure. High-tech and healthcare industries are also expected to be major beneficiaries of the “Jerusalem 5800” Master Plan.

Evicting Palestinians Using Urban Planning and the “Law”

While Israel works on creating Jerusalem as a business hub that attracts Jews and offers them employment opportunities, the problems faced in East Jerusalem are legion. They include a squeezed Palestinian business and trade sector, a weakened education sector, and a debilitated infrastructure. The result of the suffocation of East Jerusalem’s potential can be seen in the high poverty rates, with 75% of all Palestinians in East Jerusalem – and as many as 84% of children – living below the poverty line in 2015. In addition, there is a growing identity crisis in East Jerusalem, particularly amongst the youth, due to its isolation from the rest of the OPT, the leadership and institutional vacuum, and the loss of hope in the possibility of positive change. The Wall is one of the most important demographic measures Israel has put in place to ensure a Jewish majority in Jerusalem and enforce Israel’s de-facto political borders of Jerusalem, thus transforming it into the largest city in Israel. The Wall is built in such a way as to enable Israel to annex an additional 160 km2 of the OPT while physically separating more than 55,000 Jerusalemites from the city center. Planning and development in neighborhoods that are now beyond the Wall is extremely poor and governmental and municipal services are virtually absent, despite the fact that the Palestinians who live in these areas continue to pay the Arnona (property) tax. Urban planning is another major geopolitical and strategic tool Israel has used since 1967 to tighten its grip over Jerusalem and constrain the urban expansion of Palestinians as part of its efforts to Judaize the city. Urban planning is at the heart of the 2020 Master Plan, which views Jerusalem as one urban unit, a metropolitan center, and the capital of Israel. One of the main goals of the plan is to “maintain a solid Jewish majority in the city” by encouraging Jewish settlements in East Jerusalem and by reducing negative migration. Among other things, the plan aims to build affordable housing units in some existing Jewish neighborhoods as well as by building new neighborhoods. The plan also envisages connecting Israeli settlements in the West Bank, geographically, economically, and socially, to Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.

Evicting Palestinians

2,300 dunums planned for Palestinian construction vs. 9,500 dunums for Israeli Jews. (Nasrallah, 2015)

55.7% of additional housing for Palestinians through building within existing urbanized areas; 62.4% of Israeli Jewish building to happen through expansion of urban areas (including settlements).

$30,000: Approximate cost of building permits in Jerusalem. (source: author’s interview)

The 2020 Master Plan recognizes the housing crisis suffered by Palestinians, the inadequate infrastructure in Palestinian neighborhoods, and the dearth of public services provided. It aims to enable the densification and thickening of rural villages and existing urban neighborhoods; restore the Shu’fat refugee camp, which lies within Jerusalem’s Israeli-defined municipal borders; and implement infrastructure projects.

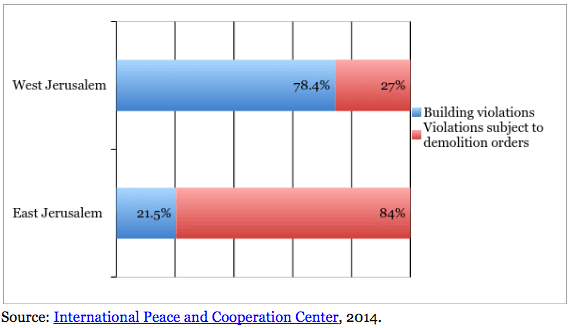

However, while on the surface it appears that the Plan has an equal interest in Palestinian areas, it is actually discriminatory. It does not take into account the Palestinian growth rate in East Jerusalem and the accumulated scarcity of housing.3 It allocates only 2,300 dunums (2.3 sq. km.) for Palestinian construction compared to 9,500 dunums for Israeli Jews.4 Moreover, most of the new housing units proposed for Palestinians are located in the northern or southern areas of East Jerusalem, rather than in the Old City, where the housing crisis is the most acute and where the settlement activity is also the most intense.In addition, (62.4%) of the increase in Israeli Jewish building will happen through expansion and building of new settlements, thus increasing Jewish territorial control. By contrast, more than half (55.7%) of the addition of housing for Palestinians will happen through densification, i.e. building within the existing urbanized areas, including through vertical expansion. Moreover, while Palestinians tend to have higher household densities and build at lower densities per dunum than the average, Israeli Jewish areas have lower household densities but build at larger densities than the average.5Furthermore, the plan’s proposals to address the housing crisis in East Jerusalem will most likely remain ink on paper due to serious barriers to their implementation. In fact, several preconditions must be met before the Israeli authorities issue building permits, including an adequate road system (building permits for six-story buildings is conditional on access to roads that are at least 12 meters wide); parking spaces; sanitation and sewage networks; and public buildings and institutions. Palestinians have no control over these requirements, which are the responsibility of the municipality; needless to say, this makes it extremely hard for Palestinians to build new houses.6 The plan also neglects the shortage in classrooms, health facilities, commercial areas, and other public institutions necessary to meet the demand of the growing Palestinian population. The Palestinian presence in Jerusalem and the development of Palestinian neighborhoods is also severely constrained by the plan’s commitment to “a strict enforcement of the laws of planning and building…to impede the phenomenon of illegal building.” However, only 7% of building permits in Jerusalem were issued to Palestinians in the past few years. Israel’s discrimination in issuing building permits to Palestinians, combined with the high cost of these permits (around $30,000, according to information shared with the author), has forced many Palestinians to build illegally. Palestinians also face discrimination when it comes to enforcement of regulations. According to a report by the International Peace and Cooperation Center, 78.4% of building violations took place in West Jerusalem between 2004 and 2008, compared with 21.5% in East Jerusalem. Yet, only 27% of all violations in West Jerusalem were subject to judicial demolition orders, compared with 84% of violations in East Jerusalem.  Furthermore, in addition to the emotional impact and instability caused by the demolition of their home, as well as the lost investment and belongings, Palestinians must also pay “illegal construction” fees to the Israeli municipality to cover the costs of house demolitions, generating a large income for the Israeli municipality. OCHA estimates that between 2001 and 2006, the municipality collected an annual amount of NIS 25.5 million (around $6.6 million) for ‘illegal construction.’

Furthermore, in addition to the emotional impact and instability caused by the demolition of their home, as well as the lost investment and belongings, Palestinians must also pay “illegal construction” fees to the Israeli municipality to cover the costs of house demolitions, generating a large income for the Israeli municipality. OCHA estimates that between 2001 and 2006, the municipality collected an annual amount of NIS 25.5 million (around $6.6 million) for ‘illegal construction.’

The 2020 Master Plan is thus a political plan that uses urban planning as a tool to ensure Jewish demographic and territorial control in the city. The plan also supports “spatial segregation of the various population groups in the city” and considers it a “real advantage.” It aims to divide Jerusalem into various planning districts based on ethnic affiliation in which no area would combine both Palestinians and Israeli Jews.

It is worth noting that state institutions are not the only ones involved in the Judaization of Jerusalem. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and religious organizations also take part in remaking urban space. The right-wing organization Elad, for example, has as its main goal settling Jews in the Palestinian neighborhood of Silwan and running tourist and archeological sites, especially in the Silwan neighborhood – which they call the “City of David” – Elad is seeking to re-create Jerusalem as a Jewish city with a predominantly Jewish history and heritage by erasing the Palestinians’ physical presence as well as their history. Elad employed 97 full-time workers in 2014 and, according to Haaretz, received donations of more than $115 million between 2006 and 2013, making it one of the wealthiest NGOs in Israel. Other organizations involved in changing the demographic composition of Jerusalem include Ateret Cohanim, which seeks to create a Jewish majority in the Old City and in Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem.

Israel has also been using law as a tactic to evict Palestinians and appropriate their land, so as to ensure its sovereignty and control over Jerusalem. As recently as 15 March 2015, the Israeli Supreme Court activated the Absentee Property law. This law was issued in 1950 with the aim of confiscating the property of Palestinians who were expelled during the 1948 Nakba. It was used as the “legal basis” to transfer the property of displaced Palestinians to the newly established State of Israel. After 1967, Israel applied the law to East Jerusalem, which allowed it to appropriate the property of Jerusalemites whose residence was found to be outside Palestine. The law newly activated in 2015 enables Israel to confiscate the property of East Jerusalem Palestinians currently living in the West Bank, and to consider their property in East Jerusalem as “absentee property.”

Furthermore, while Palestinians cannot claim the properties they lost in 1948 or in 1967 in what is now West Jerusalem, Israel’s Supreme Court has ruled in favor of Israeli settlers’ claims to win “back” homes that UNRWA had given to Palestinians who had fled West Jerusalem and Israel in 1948. In other words, the Supreme Court is being discriminatory since this law applies to Jews looking to return to property they had before 1948 but does not apply to Palestinians.

Another controversial and dangerous law is the third Generation law, which targets properties that were rented before 1968 and that are supposed to be protected by law. According to the new law, the protection period ends with the death of the third generation of Palestinian tenants after which the property goes back to its original owner, who are mainly Jews who owned the property before 1948. According to Khalil Tufakji, more than 300 Palestinians now face the threat of eviction from their home. In Silwan alone, 80 court orders threaten hundreds of Palestinians with eviction.

Saving Jerusalem

Since 2001, Israel has closed at least 31 Palestinian institutions, including the Orient House, the former headquarters of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), and the Chamber of Commerce and Industry. The Governorate of Jerusalem and the Ministry of Jerusalem Affairs are also prohibited from working in Jerusalem, and are forced to operate out of a building in Al-Ram, which lies to the northeast of Jerusalem and is outside the Israeli-imposed municipal boundaries of the city. Given the leadership and institutional vacuum Israel has created in East Jerusalem, it is especially challenging to find ways to rebut its colonization of the city and dispossession of its Palestinian population. In the course of the research for this policy brief, I had the opportunity to speak to representatives of several organizations, official bodies, and community groups. There was broad agreement that one of the most urgent steps that should be taken is to establish popular committees in each East Jerusalem neighborhood. Such committees could raise East Jerusalem residents’ awareness about their rights as residents and about Israel’s plans for the future; encourage voluntary work; monitor and prevent Palestinians from selling their land to Israeli Jews; represent the neighborhood at national forums; and cooperate with each other to reinforce their efforts to defend Palestinian land.Indeed, once these committees have been established in all neighborhoods, they could form what Jerusalemite organizations believe is also urgently needed: A representative body for Jerusalem at the national level, an inclusive body that would include the Jerusalem Governorate, representatives of civil society organizations and the private sector as well as independents. This body would work as a channel between Palestinians in East Jerusalem and the PA as well as with the rest of the world. Such a representative body could work on three main fronts:1. The PA/PLO. A representative body for Jerusalem could lobby the PA/PLO to propel Jerusalem to the forefront of the Palestinian government’s commitments and ensure that it receives the budget and other support it needs in order to counter Israeli Judaization policies.2. The Arab and international community. In this sphere, a representative body for Jerusalem should take the lead in advocacy, lobbying and campaigning at the regional and international level, in coordination with the Palestinian Diaspora. For example, Jordan should be lobbied as Custodian of Holy places in Jerusalem to help maintain a secure environment for Palestinians in East Jerusalem. Other Arab countries, in particular Morocco and Saudi Arabia given their special relationships with Jerusalem, should also be mobilized. More efforts should be made to reach out to countries that have already shown solidarity with Palestinians, such as Sweden, Latin American countries, and the BRICS among others, so that they might use their good offices directly and in collaboration with other countries to hold Israel accountable for its illegal annexation and colonization of East Jerusalem. The fact that East Jerusalem is part of the occupied West Bank is a point that is often neglected in the official discourse and that should be emphasized. These countries should also use their good offices, working with the PLO/State of Palestine, at the UN at all levels, including the Security Council, the General Assembly, the Human Rights Council, and the UN’s programs and specialized agencies to expose Israeli policies in East Jerusalem, and call on member states to fulfill their legal obligations. In particular, member states should activate Security Council Resolution 478 of 1980, which declared “all legislative and administrative measures and actions taken by Israel, the occupying Power, which have altered or purport to alter the character, legal status and demographic composition of Occupied East Jerusalem and the rest of the Occupied Palestinian Territory, are all null and void and have no validity whatsoever.”

The European Union (EU) also has an obligation to ensure full compliance with the principle of non-recognition of Israel’s sovereignty over East Jerusalem. The EU should translate its rhetoric into effective measures by halting all direct and indirect economic, financial, banking, investment, academic, and business activities in Israeli settlements in East Jerusalem and throughout the rest of the OPT.

The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) could play a major role in safeguarding Palestinian rights in East Jerusalem, providing direct support as well as in lobbying the EU and the UN to provide support and to take measures to stop and reverse Israel’s violations. Such measures could include the establishment by the UN and/or the EU of a register of Israeli violations of human rights and the damage incurred by Palestinians as a result of Israeli Judaization policies and settlement expansion in East Jerusalem and in the rest of the OPT.

It is also vital to create a funding body or a development bank to overcome the lack of funding, which is one of the major issues faced by Palestinian institutions in East Jerusalem. Such a development bank could have several functions, including: providing credit facilities since most loans are only available at very high interest rates; helping to finance the development of the housing sector; and providing incentives to encourage investment and assist in the revival of the trade sector. The Palestinian private sector and Palestinian banks within and outside Palestine should also embrace their responsibilities and be part of this development bank.

3. Palestinian communities in their homeland as well as in the Diaspora. These communities should help to develop and project a clear vision and operational strategy for Jerusalem. Practical measures should be identified to counter Israel’s Judaization policies; enhance the productive capacity of the Palestinian economy in East Jerusalem and strengthen its links with the economy of the West Bank and Arab world; promote the tourism sector to support the limited economic development possible under occupation; revive the cultural and economic status of the Old City; enhance the educational and health sector; and foster the integration of Palestinians in East Jerusalem into the rest of the OPT.

Furthermore, the existing legal bodies that offer legal assistance to Palestinians in East Jerusalem – e.g. regarding revocation of residency IDs, family unification, land appropriation, house demolitions, and zoning and planning – should coordinate their efforts.

Palestinian civil society, particularly the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement has a vital role to play in targeting Israeli plans for tourism and high tech in Jerusalem, through campaigns to boycott Israeli academic and cultural institutions as well as businesses that are involved in the Judaization of Jerusalem.

The development of a coordinated media strategy is urgently needed to raise Palestinian voices in a challenge to Israel’s discursive power and its de-historicized representation of Jerusalem. Academics and policy analysts also have a vital role to play: There is a dearth of research on the socio-economic development of East Jerusalem as well as Israel’s master plans for Jerusalem, with very few think tanks working in East Jerusalem. Future research should also move beyond diagnosis of problems to devise creative solutions, using a proactive approach rather than a reactive one. The gap between academics and policy makers needs to be bridged to ensure that all efforts are united towards the objective of achieving self-determination, dignity, freedom, and justice.

- Al-Shabaka publishes all its content in both English and Arabic (see Arabic text here.) To read this piece in French or Italian, please click here or here. Al-Shabaka is grateful for the efforts by human rights advocates to translate its pieces into French and Italian, but is not responsible for any change in meaning.

- The author thanks the Heinrich-Böll-Foundation’s Palestine/Jordan Office for their partnership and collaboration with Al-Shabaka in Palestine. The views expressed in this policy brief are those of the author and therefore do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the Heinrich-Böll-Foundation. The author also thanks the Jerusalem Industrial Chamber of Commerce, the Civic Coalition for Human Rights, the Sinokrot Core Group, the Jerusalem Governorate, and PASSIA for their time and the information they shared.

- Ir Amim, 2009. “Too little too late. The Jerusalem Master Plan.”

- Rami Nasrallah, 2015. “Planning the Divide: Israel’s 2020 Master Plan and Its Impact on East Jerusalem,” In: Turner, M. and Shweiki, O. (ed.), Decolonizing Palestinian Political Economy: De-Development and Beyond.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.