- Topics

-

Topics

See our analysis on civil society and how it shapes culture, politics, and policies

Read our insights on the shifting political landscape and what it means for Palestine

Learn more about the policies and practices shaping the Palestinian economy

Strengthen your understanding of the unique conditions for Palestinian refugees across the Middle East

-

- Analysis

-

Analysis

In-depth analysis on existing or potential policies that impact possibilities for Palestinian liberation.

Insights and perspectives on social, political, and economic questions related to Palestine and Palestinians globally.

Concise analysis into a specific policy, its background and implications.

Commentary that brings together insights from multiple analysts.

Compilations of past Al-Shabaka works surrounding a specific theme.

Longer-form, ad hoc projects that seek to confront research questions outside the scope of our regular analysis.

A policy-driven research initiative by Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network.

Our monthly webinar series that brings together Palestinian experts.

Featured

While it remains unclear how and when Israel will respond to Iran’s operation, geopolitics have undoubtedly already shifted. In this roundtable, Al-Shabaka analysts Fadi Quran, Fathi Nimer, Tariq Kenney-Shawa, and Yara Hawari offer insights on the regional impact of Iran’s recent maneuver and situate the ongoing genocide in Gaza within this broader context.

While it remains unclear how and when Israel will respond to Iran’s operation, geopolitics have undoubtedly already shifted. In this roundtable, Al-Shabaka analysts Fadi Quran, Fathi Nimer, Tariq Kenney-Shawa, and Yara Hawari offer insights on the regional impact of Iran’s recent maneuver and situate the ongoing genocide in Gaza within this broader context.

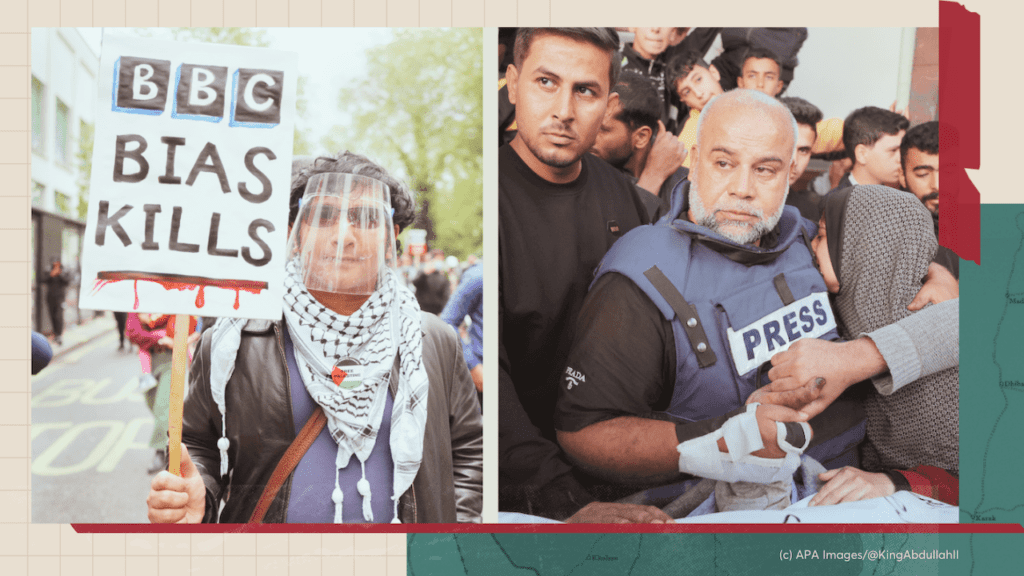

+Mainstream media coverage of the genocide in Gaza throughout the West has highlighted not only deep biases in favor of the Israeli regime, but also the ease in which Palestinians are dehumanized. In this commentary, Yara Hawari details Israel’s strategy to strip Palestinians of their humanity in the public realm, as well as the role of Western media in advancing Israel’s aims. She reveals consistent patterns of journalistic malpractice since October 7, 2023, and concludes that the Western outlets are inescapably complicit in the Israeli regime’s genocide against the Palestinian people of Gaza.

+Mainstream media coverage of the genocide in Gaza throughout the West has highlighted not only deep biases in favor of the Israeli regime, but also the ease in which Palestinians are dehumanized. In this commentary, Yara Hawari details Israel’s strategy to strip Palestinians of their humanity in the public realm, as well as the role of Western media in advancing Israel’s aims. She reveals consistent patterns of journalistic malpractice since October 7, 2023, and concludes that the Western outlets are inescapably complicit in the Israeli regime’s genocide against the Palestinian people of Gaza. Yara Hawari· Apr 3, 2024

Yara Hawari· Apr 3, 2024

-

- Resources

- Media & Outreach

- The Network