If the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) were to be revived, its institutions would need to achieve the goals for which they were created: liberation. For the education sector, this means that PLO institutions would need to minimize the social and political division of Palestinians inside and outside colonized Palestine, including in their future visioning. This role is not limited to the PLO’s Education Department and other explicitly related departments; it also extends to education-oriented bodies once affiliated with the PLO, whose connection should be restored, such as the General Union of Palestinian Students and the General Union of Palestinian Teachers, as well as to departments and bodies tasked with ensuring democratic political processes for Palestinians across the world.

This section focuses on the implications of the PLO’s revival for the education of Palestinians across colonized Palestine and the diaspora.

Funding

If it were to be revived, the PLO would need to maintain its political independence from its funders, whether from the Arab League, individual Arab states, or other sources. Ideally, it would secure enough funding to serve as the main provider of education services to Palestinians across colonized Palestine and throughout the diaspora. The PLO’s funding of the education sector would mean building on existing educational institutions and formulating their goals to reflect those of the PLO. For example, even if UNRWA continues to provide education to refugees, the PLO would need to maintain a supervisory role to ensure that the Palestinian character of educational programs everywhere is consistent and intact, in order to unite Palestinians behind a singular political vision, regardless of their place of residence.

In this role, the PLO would also need to empower bodies such as teacher and student unions, as well as education departments, to ensure the liberatory quality of educational spaces and reinforce Palestinian national identity. Providing funding for student and teacher unions would incentivize Palestinians to create inclusive, democratic, and political initiatives such as conferences, which would further foster unity and secure the rights of workers and students.

Quality

The revival of the PLO’s educational institutions represents an opportunity to improve the quality of Palestinians’ education, wherever they may be, by allowing them to create new educational departments and programs that reflect their specific political and social realities. Further, as with UNRWA programs in refugee camps across the region, the PLO would need to monitor, hold accountable, and guide PA efforts to rebuild the education sector in the West Bank, as well as those of Hamas in Gaza. This could entail the formation of committees to evaluate education programs in different locations of Palestinian residence, and to recommend additional budgets and new opportunities to enhance the quality of education. The revival of the PLO could also provide the chance to develop a strategy to reduce class differences that limit lower-income Palestinians’ access to higher quality education.

Infrastructure

Educational infrastructure under a revived PLO depends on whether its revival is initiated from within the political elite controlling the PLO, or if it is brought about by popular pressure. If PLO institutions are revived in the current status quo of PA domination, education infrastructure would likely remain unchanged. However, worker and student unions’ democratic influence on these structures may grow. This would mean, for example, that Fatah and its loyalists would not monopolize jobs, particularly senior positions. The unions would supervise improving workers’ conditions in general, as well as exert pressure toward improving educational quality for teachers and students.

A revived and rebuilt PLO would reinvigorate the General Union of Palestine Students, allowing Palestinian students in universities across the world to become involved in public and political life, contribute to bolstering the quality and structures of education, and influence political decision-making when it comes to education. Creating these political spaces can foster unity and political engagement among Palestinians everywhere.

Content (Curricula)

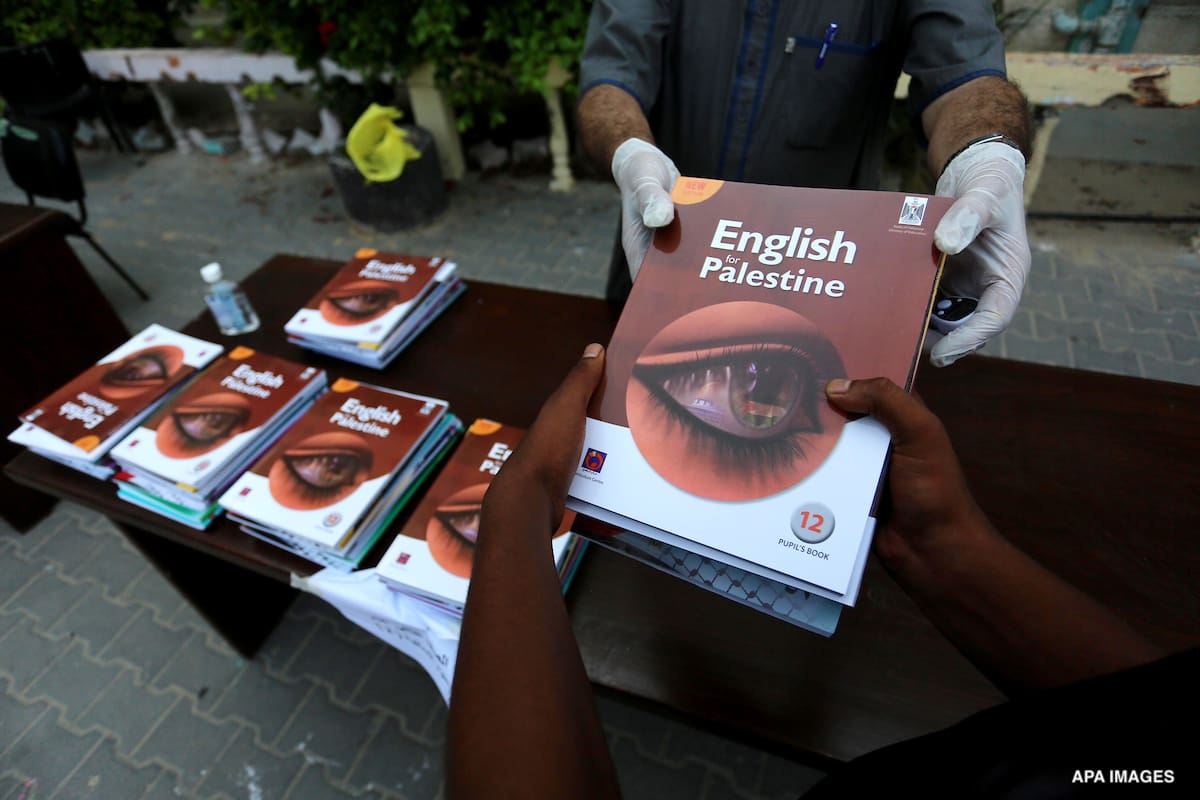

The PLO’s revival would manifest in standardized Palestinian curricula across the different locations where Palestinians reside. The PLO would need to oversee the standardization process in order to ensure a shared political and social future vision that is reflected in all curricula and pedagogies.

Standardized Palestinian curricula would ensure that Palestinians feel united, while acknowledging their unique experiences across colonized Palestine and the diaspora. Indeed, between 1948 and 2006, Palestinian were taught using different curricula — Jordanian in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and in refugee camps in Jordan, Egyptian in Gaza, and Syrian and Lebanese in refugee camps in Syria and Lebanon. This was partially overcome through the development and standardization of the first Palestinian curriculum in 1996 in Gaza and the West Bank, but it did not extend to refugee camps in Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan. Moreover, Palestinian curricula in Gaza and the West Bank have faced many obstacles, including international donors’ influence over content, such as conditional funding designed to ensure the absence of political visions of independence and liberation from Palestinian textbooks.

Reviving PLO institutions would solve many of the dilemmas hindering the production of modern Palestinian curricula that reflect the social, economic, and political visions of the Palestinian people. Yet UNRWA and regimes of neighboring countries that host Palestinian refugees would likely impede efforts to teach Palestinian curricula in refugee schools, out of fear that it could create independent Palestinian political spaces that challenge the status quo. This is consistent with UNRWA’s policies, which have always leaned toward settling refugees in their places of residence. Therefore, it is unlikely that all Palestinians would be able to use their own curricula even with the revival of the PLO. Ultimately, conditions hinge on the PLO’s influence and ability to adopt a political path toward return in a way that also encourages host countries to accept the teaching of Palestinian curricula.

Mohammed Alruzzi is a Lecturer in Childhood Studies at the University of Bristol, the UK. He earned his PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of Fribourg, Switzerland. Before that, he completed his Master’s degree in Childhood Studies at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, UK. Alruzzi has worked with many international non-governmental organisations and UN agencies, including Mercy Corps, Terre des Hommes, the Norwegian Refugee Council, World Vision and UNICEF. Through his work experience, Mohammed has developed extensive multidisciplinary expertise in children issues. His research interests include child labour, child detention and education policy.