Executive Summary

The Palestinian people and their national representative, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), face critical challenges that they are ill prepared to address. The strong national movement that the PLO established in the 1960s, pulling together dispersed Palestinian refugees and exiles to face Israel’s colonial project and reclaim their homeland, is now much diminished. This is in large part due to the growth of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), which was established under the Oslo accords in 1994 as the nucleus of a Palestinian state, and which itself is now hollowed out by Israel’s unremitting settlement building and other human rights violations. Its goal of an independent sovereign state is more elusive than ever.

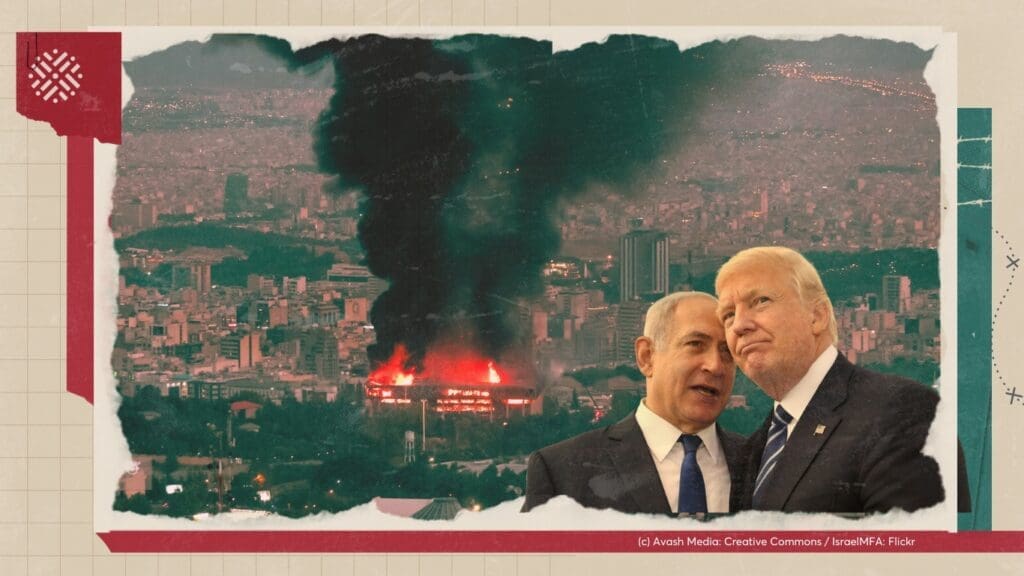

The grievously weakened Palestinian bodies are not equipped to face the threats posed by Israel’s colonization and further annexation – which were openly support by the outgoing Trump administration – as well as by the Jewish Nation State Basic Law that leaves Palestinians in both Israel and the OPT in a precarious legal position. Meanwhile, the Israeli government has been increasingly successful at neutralizing key Arab, European, Asian, African, and Latin American countries, eroding the international consensus on a just resolution that secures inalienable Palestinian rights. A major blow was dealt in late summer 2020 with the decision of the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain to normalize relations with Israel.

The failure of the PLO to imagine that such a reversal in US policy could happen or to understand the fragility of the diplomatic approach is a sign of its failure to see national liberation as a popular struggle. These grievous setbacks are all taking place against the physical threat that the COVID-19 pandemic poses to the already vulnerable Palestinian populations in Gaza, East Jerusalem, and Lebanon and Syria. There have been many initiatives to tackle these challenges, most recently a renewed commitment in September 2020 by Fatah, Hamas, and other Palestinian factions to end their divisions. There are also many studies that seek to map a way forward (including a recent report crafted by 12 Al-Shabaka members – Reclaiming the PLO, Re-Engaging Youth).

This study is the first of its kind on the PLO diplomatic corps and its engagement with the Palestinian diaspora. The assumption underlying the study is that a more active and regular engagement between the diaspora and the PLO diplomatic missions would strengthen the PLO and its representative character, and help to revive some of the power and potential of the diaspora that was in evidence in the 1970s and 1980s. The idea for such a study came about when a member of the team spoke to a young diplomat who explained how they managed to achieve important work to protect Palestinian rights despite the internal difficulties and lack of clarity about the objectives and strategies of the national project. This sparked our interest in the activity of the corps and in particular its relationship with the Palestinian diaspora, which had once worked closely with the representatives of the PLO and which has now become increasingly alienated from it. As a former diplomat put it, “The diaspora is no longer seen as a priority for the PLO; as a result, we lost what used to be a superpower.”

The Alienation of the Diaspora

The study reviews the way in which the PLO arose in the diaspora among exiles and refugees in the 1960s, built connections with the Palestinian people, established Palestinian national identity on the global stage, and advanced international recognition of Palestinian rights. Indeed, the PLO prioritized the establishment of representative offices in foreign capitals as a way to build the necessary infrastructure for global advocacy in support of Palestinian self-determination and sovereignty. Diaspora Palestinians were, and some still are, a vital component of that infrastructure within their adopted countries.

The Oslo Accords that began in 1993 changed the engagement between the PLO and the diaspora. Many diaspora constituencies withdrew active support for the PLO because of their opposition to the signing of the interim agreement which legitimated Israeli presence in the OPT and undermined refugee rights and claims. Partly as a result, knowledge of the PLO’s history and the vital role it played in the Palestinian struggle for self-determination has been lost to the post-Oslo generations. Most see the PLO as indistinguishable from the PNA, which represents only the Palestinians of the OPT.

Many youth in the homeland and in exile are unaware of the role the PLO has played in preserving Palestinian national identity and how effective it has been in shifting the world’s view of the Palestinian cause from a mere humanitarian concern to a legitimate struggle for national liberation. There is also insufficient awareness of how PLO representatives have worked to sustain the international consensus around Palestinian rights – many sacrificing their lives to do so in the 1970s and 1980s – and how these norms underpin legal efforts to end Israeli impunity, provide accountability to Palestinian victims, and stem ongoing displacement and dispossession in what remains of the Palestinian homeland. That pro-Israel advocacy groups and lobbyists expend millions of dollars in an attempt to delegitimize such Palestinian diplomatic and legal initiatives underscores the importance of the PLO’s work in these fields. Without the PLO, there would be no recognized national body representing Palestinians in critical international forums.

The PLO’s representativeness has been negatively impacted by the physical and political fragmentation of the Palestinian body politic, and especially by the rivalry between the two main political factions, Fatah and Hamas. That rivalry is also reflected in the relationship between the PLO’s diplomatic corps and the diaspora, many of whom sympathize with, or are members of, the Islamic movement which is not part of the PLO. Moreover, the singular focus of Palestinian national institutions on establishing the trappings of statehood before securing Palestinian rights has compromised the corps’ former role of representing the liberation movement abroad and diverted its attention from driving international solidarity and support for Palestinian rights. In fact, almost all the responsibilities of the PLO’s Political Bureau – the central organ for executing the PLO’s political platform and liberation strategy – were transferred to the PNA’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) although the PNA was never mandated to handle foreign affairs. This sent a strong signal to Palestinian refugees and exiles that their voice and their experience of displacement and dispossession was no longer the central priority of the organization.

As will be discussed in this study, the PLO’s responsibility for the corps now hangs by a thread which may be irreparably cut should the chair of the PLO Executive Committee no longer also hold the seat of the presidency of the PNA. Though all Palestinian embassies and missions are deemed PLO offices, most of the responsibilities for the missions come under MoFA’s management. A critical responsibility retained by the PLO by virtue of its international legal personality is the signing of treaties and bilateral agreements, including a comprehensive peace agreement with Israel. Should the overlapping roles between the PLO chair and the PNA president no longer exist and should the PLO fail to reassert its authority over international relations and the diplomatic corps, the Palestinian national cause could be reduced to a territorial struggle over what is left of the Palestinian homeland inside the OPT, and the diaspora – along with its interests and claims – will be completely unmoored from the national liberation movement.

Listening to the Diplomatic Corps

In our interviews with the diplomats, we found that the confusion of PLO and PNA responsibilities and authorities impacts the ability of the diplomatic corps in many ways, including in its ability to engage with the diaspora. Another key concern, repeatedly shared, was the lack of a political direction and strategy within which the diplomats could frame their work. They also noted other problems due, in part, to a lack of transparency in the selection of mission staff, and inefficiencies and infighting in some missions key to the Palestinian cause where there had once been a high degree of effectiveness. These challenges, which are also common in the diplomatic offices of sovereign states and which are not new to the PLO, are not ones a national liberation movement can afford. On the other hand, the study also found that PLO missions led by seasoned diplomats and with effective staff have been capable of advancing Palestinian interests within the country of posting or the international body to which they were assigned.

Another challenge experienced within some missions related to the role and responsibilities of the diplomatic corps as well as the chain of authority which were not clearly defined or understood by staff. For example, some diplomats considered themselves PNA diplomats, while others were emphatic about their belonging to the PLO. This cognitive dissonance created something of a division between those who saw themselves as revolutionaries and activists, and others who understood their role as that of traditional civil servants.

The diplomatic corps’ ability to function effectively has also been impacted by the Fatah-Hamas divide, the PNA’s record of human rights violations, its lack of a democratic mandate, and security collaboration with Israel, all of which have served to alienate both Palestinians and the solidarity community from the missions. The missions’ loss of this support makes it difficult for the diplomatic corps to present a strong and unified message in tandem with the diaspora, at great cost to the national liberation movement. Certainly, an effectively functioning and well-resourced Palestinian mission working closely with the diaspora community and solidarity movement would be better placed, for example, to respond to Israel’s campaign to conflate criticism of its occupation, siege and other rights violations with anti-Semitism. In fact, the inability to mobilize the strength and power of some diaspora communities in countries where their numbers are politically significant means diplomats are more susceptible to being cold-shouldered by a host government concerned with appearing insufficiently pro-Israel. When the diaspora and solidarity community do not value the work of the PLO’s mission, it is easier for the host government to eschew engagement with Palestinian diplomats.

Listening to the Diaspora

The study focuses on three specific events to better understand how and when the diaspora engages with the diplomatic corps on a matter of national concern. Two of three events gave contrasting insights: the bid for Palestinian statehood presented a positive engagement between the diaspora and the corps while the PNC elections presented a negative one. The third event, the Trump administration’s decision to move the US embassy to Jerusalem seemed to show the weakness of the PLO given what appeared to be little engagement with the diaspora.

The PLO/PNA effort to upgrade Palestine’s status at the UN from observer to non-member state was generally viewed as a well-organized effort with clear goals, direction, communication, and messaging from headquarters. The corps worked as a smoothly functioning system not just in the country of posting, but across countries and regions, and as a result, media coverage increased. Furthermore, as members of the corps put it, they viewed every effort to formalize recognition of Palestine as a source of power for the Palestinian people in their search for ways to respond to the extreme right-wing government in Israel and its settler movement, as well as the regimes that were eschewing international law.

As for the diaspora, some activists who had previously distanced themselves from the PLO/PNA willingly engaged with the corps’ representatives to advance the big for statehood, in particular because it reasserted Palestinian agency and challenged US control of the agenda. This shows the potential for mobilization and joint action by the PLO missions and the diaspora. In other cases, however, the missions did not engage with the diaspora on the issue even though the diaspora was keen to do so.

The effort to select representatives for the convening of the PNC in 2018 had a negative impact on the diaspora. Although Palestinian community organizations are themselves intended to nominate their own members, the interviews made clear that the missions were closely involved in the selection. In one country where the community had previously given PNC elections the highest importance, unilateral moves were said to have been taken by the mission, and in the end, representatives were nominated “by Ramallah.” In another country, the process was said to be “totally ad hoc” and characterized by a lack of transparency. In a third, the process was described as having led to a PNC “that absolutely doesn’t represent the Palestinian people.” Overall, the diaspora’s experience in the 2018 PNC appears to have reinforced its alienation from the PLO.

As for the Trump decision to move the US embassy to Jerusalem, the PLO and PNA appear to have missed an opportunity to engage the diaspora and solidarity movement to amplify Palestinian voices and increase the pressure for Palestinian rights.

Beyond these three specific areas of focus, the research team identified other areas of concern regarding diaspora engagement with the PLO:

- Many Palestinians in the diaspora and in the homeland are strongly opposed to PLO/PNA policies such as security coordination with Israel. Among other problems, this leads to contradictory messages being communicated about Palestinian rights to the host country and to solidarity activists.

- Some missions are less effective at advancing the Palestinian cause due to a bureaucratic culture that results in little engagement with the host country, and even less with the diaspora, as well as little outreach to the media or country influencers. As a result, the field is left open for the Israeli lobby to dominate the discourse and policy on Palestinian rights.

- In other cases, there was a tendency to focus efforts on governments rather than on the diaspora and the solidarity movement which were well-placed, and in some cases, better-placed, to advance a change in discourse.

- In some countries where there was an active diaspora, it was not clear to what extent the broader Palestinian community was aware of the work of the mission, its responsibilities, or how to hold it accountable as their representative.

Finally, a major deficiency in the diplomatic corps-diaspora relationship is the limited – and in most cases, nonexistent – engagement with groups and individuals associated with, or perceived to be associated with, Hamas and other Islamist organizations. This is largely due to the Fatah-Hamas schism that is reflected in how the Fatah-ruled PLO prioritizes its work and relationships at the mission level, but it may also be attributed to legal limitations involving Hamas within the host country.

Despite these criticisms, almost none of the interviewees questioned the legitimacy of the PLO as the national representative organization of the Palestinian people. Indeed, despite the rejection of security coordination, authoritarianism, and the other problematic policies of the PNA, where the goals are well-defined and there is good outreach and communication between the corps and the diaspora, members of the diaspora have shown receptivity to working with the mission. This could be built upon to reform and strengthen the PLO to fulfill its role as a representative body.

Recommendations to Diaspora Palestinians

- Diaspora Palestinians should develop a regular relationship with the PLO mission and communicate their views and expectations, as well as their critiques of policies that undermine Palestinian rights. Until actions are taken to reform structures of the PLO and PNA, direct engagement with the mission is the only way for the diaspora to be heard by a representative of the national movement.

- More direct engagement could also enable members of the diaspora to assist PLO representatives in addressing various challenges. For example, the diaspora can play a constructive role in: convening forums to discuss the Palestinian national project; helping to bridge the split between Fatah and Hamas; insisting on steps to end security coordination with Israel as well as authoritarianism in Palestine; and helping to push back against Israel’s campaign to conflate criticism of its actions with anti-Semitism.

- Diaspora representatives should demand that the PLO Executive Committee appoint and empower an ombudsperson to respond to diaspora complaints and concerns about a mission’s work where those complaints cannot be addressed at the mission level.

- The diaspora should prioritize education, particularly for the youth and emerging leaders, about the history of the PLO, its achievements, the sacrifices that many PLO members – including of the diplomatic corps – have made, and the external challenges the organization is facing.

Recommendations to the PLO

- The PLO must drive an initiative to revisit the national project. A renewed vision backed by serious planning and engagement, is needed to secure Palestinian rights and to help address the challenges facing Palestinians and their movement, including Israel’s normalization drive and the health and economic impacts of COVID-19.

- The Central Council must review the purposes and functions of the PNA, including its relationship to the PLO Political Bureau, which should reassert its authority over the diplomatic corps. The Council should also review the division of responsibilities between the various PLO departments to limit overlap. As part of the review, an assessment should be carried out on how prioritization of statehood has impacted the Palestinian struggle for liberation and the work of PLO missions around the world.

- The PLO should rebuild capacities within its Department of Popular Mobilization, which once contributed to connecting the diaspora to the work of the organization. The department should develop new strategies to better engage with the diaspora in line with renewed national goals and strategies.

- The PLO executive committee should create and empower an office of ombudsperson to enable the diaspora to communicate issues related to the operation of the missions.

- Until the Political Bureau is reactivated to assume its role in directly managing the diplomatic corps, MoFA must be vigilant in ensuring that the most qualified persons are appointed at all levels in a process that is transparent.

- The PLO should redouble efforts to support a national dialogue that allows all political factions and constituencies, including the diaspora, to develop a process for a representative PNC. This process must be based on transparent and agreed-upon criteria for selection of members to the PNC, and it must promote consensus-building around a renewed national project.

Preface

The vital question of how to reconstitute and strengthen the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and renew the Palestinian national project has long been at the forefront of Palestinian concerns. However, it stalled due to the bitter divisions between the major political parties, Fatah and Hamas, after the legislative elections of 2006. There is now renewed urgency to revive the national project following the normalization of relations between Israel, the United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain in 2020.1

Yet, during the discussions by Palestinian factions to map a way forward, the Palestinian diaspora and the role it could play in reviving the PLO and the national project was conspicuously absent. Rather, the focus was on elections in the occupied Palestinian territory (OPT) of the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem, despite Israel’s complete control and ability to subvert any meaningful outcomes. It is too early to judge the reconciliation initiative by the factions, but there is so far little recognition that the diaspora has freedom of action and resources that are not available to the Palestinians under occupation or to the Palestinian citizens of Israel.

This study takes up the question of how this key constituency of the PLO – Palestinian diaspora communities – might reinvigorate the PLO’s representative character so that the organization may be able to develop an effective national strategy and be better equipped to respond to the extraordinary challenges facing the Palestinian people.

The assumption underlying the study is that a more active and regular engagement between the diaspora and the PLO diplomatic missions abroad could contribute to strengthening the PLO, make it more attuned to the challenges and concerns of the Palestinian people, better position it to withstand threats to Palestinian rights and sovereignty, and contribute to the diaspora’s strategic mobilization in the countries where Palestinians reside. A PLO that is not engaged with the Palestinian people, particularly with those residing outside historic Palestine, guarantees diaspora disengagement from its representatives, which in turn guarantees a non-representative PLO. Thus, at a more fundamental level, revitalizing the relationship between the diaspora and the PLO via the Palestinian diplomatic corps is critical to the legitimacy of the PLO as a reflection of the will of the Palestinian people.

To answer the question posed by the study, the authors reviewed the diplomatic corps’ legal foundations as well as the rules governing its functions; the relationship between the PLO and the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) and how they divide responsibilities for the management of the corps; and the corps’ effectiveness by selecting representative missions to better understand the engagement within the host country and with the Palestinian communities the corps is also meant to represent.2 In addition, the study zeroes in on three specific events to assess the corps’ engagement with the diaspora: Palestine’s statehood bid between 2011 and 2012; former US President Donald Trump’s decision to move the US embassy to Jerusalem in 2017; and the PLO National Council elections of 2018 (see Annex 1 for the methodology).

Eight Palestinian missions were selected for study based on a set of criteria that included the country’s influence in global and Palestinian affairs, its regional location, the size of the Palestinian community, and our ability to identify members of the diaspora and solidarity groups in those countries. We interviewed 35 people including from the missions, diaspora, and solidarity groups, as well as former diplomats and experts (see Annex 2 for list of interviewees).

This study was always intended to be a limited exercise given the resources available to the authors and the fact that it was the first of its kind. It should be seen as the beginning of an effort to understand the structure and functioning of the PLO diplomatic corps and its contribution to the organization at large. Many challenges were faced along the way. For example, identifying the relationship between the PLO and PNA structures and finding supporting materials involved a major excavation as well as double-checking against the information provided by different sources. This was perhaps not surprising given that the PLO developed largely underground for the first decade of its existence and was attacked for years, attacks that were redoubled during the Trump administration.

Moreover, there is an ongoing but incomplete transfer of powers from the PLO to the PNA that includes the diplomatic corps and that makes it difficult to pinpoint roles, responsibilities and resources. In addition, it was difficult to secure interviews with the full complement of missions as well as with representatives of the diaspora and solidarity organizations from each of the selected countries. Nevertheless, we succeeded in securing the information necessary in which to ground our analysis and recommendations, and several former and current PLO diplomats and staff have been largely supportive of the study and its aims, as have the other interlocutors.

The study was carried out by a team of four women, all established experts and members of Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network. Nadia Hijab conceived the idea, wrote the concept note, and authored much of the report; Zaha Hassan, who came on board later in the process, undertook extensive research and authored the bulk of the report; Inès Abdel Razek conducted most of the interviews; and Mona Younis developed the methodology and interview protocols. All remained engaged throughout to produce the study.

We would like to thank Diana Buttu who played a key role in the early months, taking the concept forward, developing the approach, and participating in reviews. We would also like to thank Mazen Arafat, Leila Shahid, Jamil Hilal, and Sara Husseini for serving on the review panel; their support, feedback and dedication enriched this study tremendously. In addition, we wish to thank all those who agreed to be interviewed for this study for their time, interest, and commitment to Palestinian rights; many of the interviewees preferred to remain anonymous and we respected their wishes. And, last but not least, we wish to thank the Al-Shabaka team for their advice and support, and in particular Alaa Tartir for his detailed comments.

The study does not include an examination of the way in which the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the OPT and the countries hosting Palestinian refugees and exiles. In many cases, the pandemic promoted coordination between the diaspora and the diplomatic corps; the PNA Foreign Ministry and PLO missions worked closely with the diaspora to channel funding, medical supplies, and other support to the OPT which helped shore up the response and capacities of the Palestinian healthcare system. However, there were also reports of thousands of Palestinians stranded outside the OPT, including many students, who felt they did not get the support they needed from their missions. These issues, which involved transit countries, were mostly resolved after some weeks.

These two facets of the PLO diplomatic corps are what our study seeks to address: the potential of the corps when it is functioning at its best, as well as the problems and gaps when it is not. Our hope is that the study will renew appreciation for the potential of the PLO and its diplomatic corps, and breathe new life into the engagement between it and the diaspora so that this regular exchange of ideas and feedback may serve as a mechanism for strengthening Palestinian institutions, unifying the people, and supporting the fulfillment of the inalienable rights of Palestinians everywhere.

Zaha Hassan, Nadia Hijab, Inès Abdel Razek, and Mona Younis

Chapter 1: Addressing the Crisis of the Palestinian National Movement

The Existential Challenges Facing the Palestinian National Project

The Palestinian national project is experiencing both internal and external challenges. Internally, the most critical challenges stem from the diminished representative character of the PLO as a result of the ascendance of the PNA, a construct of the Oslo Accords principally established to guarantee Israel’s security until the conclusion of a permanent agreement. Externally, and with the erosion of the two-state solution, Israel continues to threaten de jure annexation of some 30% of the West Bank while expanding its normalization agreements with an increasing number of Arab states.

Given that the implementation of PLO decisions is now delegated to the consolidated offices of the PNA president and the PLO chairman, the necessary process of reassessing the utility and functions of the PNA has been repeatedly postponed. Although all factions pledged in September 2020 to unify their efforts to push back against normalization and to promote the national project, the overlapping competencies and powers of the PNA and PLO are likely to continue to complicate national reconciliation between the Fatah-led PNA and Hamas, which is not yet a member of the PLO and which continues to oppose the Oslo Accords signed between Israel and the PLO.

Among the most critical external challenges is the colonization of the OPT which has become entrenched both in fact and in Israeli law. The so-called Jewish Nation State Basic Law,3 giving Jewish people an exclusive right to self-determination anywhere Israel extends its sovereignty, means that Israel’s territorial intentions may not end with partial annexation of the West Bank. This leaves Palestinians in both Israel and the OPT in a precarious legal position that could set the stage for their mass displacement. And, as facts are established on the ground and laws are passed consolidating Israeli control over the West Bank, the Israeli government has been working to neutralize – with some success – international criticism from parts of Europe and the Arab world. As a result, the PLO can no longer take for granted an international consensus on a just resolution to the conflict.

Alongside this sobering reality, the stated US policy in the Middle East has shifted. The actions taken by the Trump administration, including relocating the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, and new federal legislation4 affecting the status and financial viability of the PLO, may be difficult to reverse or repeal with a new administration, even with a Democrat-controlled Congress. The so-called “peace plan” released by the Trump administration effectively green-lights Israeli annexation of parts of the occupied West Bank and promises Israel US political recognition.

A number of former US officials now argue that the US should simply get out of the business of Palestine-Israel peacemaking given the failure of the two-state project, though most do not call for ending US security assistance to Israel even as an apartheid reality is increasingly imposed on Palestinians. With the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic and the human and economic devastation that it has visited upon every corner of the world, it is unlikely that the European Union or other countries will provide the same level of support to Palestinians in the OPT. And with Gulf states beginning to normalize with Israel – and with their economies reeling from falling oil prices – the PLO and PNA will not be able to rely on financial assistance from Arab patron-states to support Palestinian steadfastness on the land.

The Focus of This Study

At this critical juncture, the PLO must reevaluate the platform it adopted in 1988 towards establishing a state in the remaining 22% of historic Palestine that was occupied by Israel in 1967, and develop a strategy toward a renewed political agenda that preserves the inalienable rights of the Palestinian people, endeavors to realize their national aspirations, and supports their presence on the land. These discussions are on the agenda of the talks between Fatah, Hamas, and other factions that began in September 2020. Any strategy, however, must be true to the PLO National Covenant pillars of “unity, mobilization and liberation,” must capture the imagination of Palestinians, must overcome their disaffection with the traditional leadership, and must inspire them to action wherever they may be. National unity, in particular, is a prerequisite to moving forward.

The next generation of Palestinians who stand to inherit the struggle for national liberation, including those in the diaspora, are disconnected from the PLO and its political program Share on XThis study takes up the question of how a key constituency of the PLO, Palestinian diaspora communities,5 might re-engage with the PLO in order to reinvigorate its representative character. By doing so, the organization may be able to develop an effective national strategy and be better equipped to respond to the extraordinary challenges facing Palestinians wherever they live. The assumption underlying the study is that a more active and regular engagement between the diaspora and the PLO diplomatic missions abroad would contribute to strengthening the PLO, make it more attuned to the challenges and concerns of the Palestinian people, better position it to withstand threats to Palestinian rights and sovereignty, and contribute to the diaspora’s strategic mobilization in countries where Palestinians reside.

We recognize that Palestinian diaspora experiences with the PLO differ from country to country and across different time periods, a subject that is worth much more in-depth study. Nevertheless, it is safe to assert that a PLO that is not responsive to the people, particularly to those residing outside historic Palestine, guarantees diaspora disengagement from diplomatic missions, which in turn guarantees a non-representative PLO. Thus, at a more fundamental level, revitalizing the relationship between the diaspora and Palestinian diplomatic corps is critical to the legitimacy of the PLO as a reflection of the will of the Palestinian people.

The Evolution of the PLO and its Representation of the Palestinian People

The Palestinian national struggle began with the forced displacement of three quarters of the indigenous population from historic Palestine in 1947-48. Naturally, justice for these refugees, premised on return and restitution of property, was and still is the principal Palestinian demand. After the PLO was founded in 1964, and more particularly, when control over the organization moved from the Arab League to the Palestinians themselves after the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, the organization offered a vehicle for the expression of the will of those in exile. Founded and led by diaspora Palestinians, the PLO found its first support6 among the largely refugee population in Gaza7 and came of age in the camps around Amman and Beirut before its forced evacuation to Tunis in 1982 that was to last a decade. After the October Arab-Israeli War of 1973, the PLO slowly began a strategic shift from refugee return and self-determination in historic Palestine to a sovereign state in occupied Gaza and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, as the end-goal of resistance. The PNC formally adopted this political program in 1988.

When the organization was able to operate openly in the OPT following the launch of the Oslo Accords in 1993, the priorities and the engagement between the PLO and the diaspora changed markedly. Hamas, as well as important secular PLO political factions with diaspora constituencies, opposed signing an interim agreement8 with Israel because they believed it would legitimize Israeli presence on Palestinian land and undermine refugee rights. Moreover, the PNA, which was created as an interim governing body, represents only Palestinian residents of the OPT. With time, discord within the PLO also festered as the organization and its various departments were hollowed out in favor of the donor-supported PNA and its ministries. While the PNA Foreign Ministry’s mandate includes “expatriate affairs,” the rights of the Palestinian refugees, in addition to diaspora interests and concerns, have been largely subordinated in favor of the political initiative to gain international recognition for the State of Palestine, and to obtain funding and support for Palestinian state-building.9

The PLO’s vitality and character have also been negatively impacted by the physical and political fragmentation of the Palestinian body politic. The two principal Palestinian political factions, the ruling-party, Fatah, and its rival, Hamas, have so far been incapable or unwilling to forge a path to national reconciliation since the 2007 schism between them, which left the Islamic movement in control of Gaza, home to almost two million Palestinians who have since then lived under a draconian Israeli siege. The failure so far to bring the Islamist factions under the PLO umbrella has contributed to weakening the national liberation movement and its ability to respond to threats as a united front.10

Though PLO policy-making bodies have periodically convened to discuss the challenges facing the movement, the resolutions they have passed calling for specific action, including ending security coordination with Israel, were left to the discretion of the chairman of the PLO. In the wake of Israel’s official declaration of its intent to illegally annex further areas of the OPT, Mahmoud Abbas temporarily stopped security and administrative coordination with Israel. It remains to be seen how the unity efforts launched in September 2020 progress and the extent to which this process will develop a blueprint for strategic action.

The next generation of Palestinians who stand to inherit the struggle for national liberation, including those in the diaspora, are disconnected from the PLO and its political program, which remains committed to an increasingly unlikely vision of an independent state in Gaza and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. This generation has had no connection with the PLO and its ancillary “feeder” mechanisms of the past, including student and professional organizations, unions, women’s groups, summer camps, and conferences,11 to name a few. Many lack an appreciation for how critical international recognition of the PLO was in establishing Palestinian national identity on the global stage and in attaining recognition of the right of Palestinians to self-determination and sovereignty. Most came of age after the Oslo Accords were signed, and consider the PLO to be indistinguishable from the PNA, which, as noted earlier, was only intended to be an interim governing body representing Palestinian residents of the OPT. In the view of these young Palestinians, the PLO as it stands now neither represents the Palestinians living on the land of Palestine, nor the more than six million12 residing outside in the diaspora.13 Thus, even if the PLO were to articulate a clear national strategy, as the situation stands today, this critical constituency would unlikely be inspired to action.

What is the Relevance of the PLO in the Diaspora?

If, as this study assumes, the PLO has lost considerable legitimacy among Palestinians within and outside of the historic homeland, why should the diaspora be concerned with rehabilitating its relationship with the PLO in the first place? And why does this study focus and prioritize the engagement and mobilization of diaspora Palestinians? Before proceeding with the study’s findings, it is necessary to make the case for the importance of diaspora engagement with the PLO, to recall the role the PLO has played in preserving Palestinian national identity, and to take stock of the extent to which it remains a critical vehicle for justice and accountability, and the realization of the national aspirations of the Palestinian people. It is also important to note the invaluable role the diaspora can and must still play in advancing Palestinian rights.

The PLO has been the embodiment of the Palestinian national movement since its founding in 1964. International recognition of the PLO, achieved a decade later, established Palestinian self-determination as an integral component of, if not a prerequisite to, resolution of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Prior to that, the Global North largely viewed the Palestinian question as a humanitarian issue that could be resolved without consultation with refugees themselves. Political recognition restored Palestine and Palestinian nationhood to international consciousness, centered it within the larger context of Arab-Israeli peace, and ultimately compelled Israel and the US to deal with Palestinians as a people entitled to self-determination and rights. Simply put, without the PLO, Palestinians would be without a national address.

The PLO recognized that maintaining a strong relationship with the Palestinian diaspora was critical to its raison d’être. Thus, only one year after its founding, the PLO established the Department of Popular Mobilization which was responsible for organizing general unions of students, women and labor syndicates, as well as councils within the refugee camps referred to above.14 These popular bodies, and the summer camps and conferences they organized15 across different countries of exile, gave the PLO some of its early activists and cadres.

Since its founding, the PLO and its representative offices have been fundamental in preserving the international consensus around the norms buttressing a just resolution to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, norms that are the basis for the UN resolutions which uphold Palestinian rights, for referrals brought to the International Criminal Court, for advisory opinions sought in the International Court of Justice, and for communications and inter-state complaints submitted to UN mechanisms such as the Committee to Eliminate All Forms of Racial Discrimination. Without the PLO, there would be no recognized national body representing Palestinians in critical forums and foreign capitals, and the international consensus and norms Palestinians rely on before multilateral institutions and governments would have been much easier to undermine or call into question. This is why pro-Israel lobby groups spend so much time and resources delegitimizing, criminalizing, and defaming Palestinian representative bodies in key capitals like Washington, DC, and Brussels.

Simply put, without the PLO, Palestinians would be without a national address Share on XDiaspora Palestinians have played a critical role in maintaining support for Palestinian rights within their adopted countries, and they are key to the fulfillment of national objectives. Many are citizens of liberal democracies where they are free to engage in advocacy, and can impact public opinion and the policies of their governments. They are not captive to the political stalemate existing between the two main Palestinian political factions and do not face the restrictions that their counterparts do in Gaza, the West Bank, and other parts of the Arab world hosting Palestinian refugees and diaspora communities. The distance between diaspora Palestinians and their historic homeland provides them with unique insights and perspective on how freedom, justice, and equality for the Palestinian people as a whole might best be pursued on the international level. Their active participation in the struggle for Palestinian liberation and rights stands to greatly enrich the national debate on strategy and tactics.

In short, at a time when Palestinian national leadership has been at its weakest and the efforts to extinguish the Palestinian national project are at their strongest, the Palestinian diaspora must be seen as a major source of power for the PLO and the Palestinian people. Because PLO missions and representative offices exist in over 100 countries,16 they have the capacity to function as a conduit between the diaspora and the PLO, enabling the sharing of information and ideas, and creating mechanisms for interaction. Strategically utilized, the Palestinian diplomatic corps and the PLO missions could play a critical role in reconnecting the diaspora to the work of the PLO, and in reinvigorating the relationship between the two as a preliminary step toward making the PLO a better representative of Palestinians wherever they may be, and toward empowering Palestinians to better serve their national cause.

Chapter 2: The Slow Erosion of the PLO’s Status

The signing of the Oslo Accords and the creation of the PNA negatively impacted the once organic relationship between the Palestinian diaspora and the PLO and its various departments.

Initially, the PNA ministries operated in parallel with those departments of the PLO meant to engage with, serve, and mobilize the diaspora. This changed over time with the result that these departments have been hollowed out almost completely in favor of the PNA ministries. As PLO Executive Committee member Hanan Ashrawi points out: “The Jerusalemites, as well as the Palestinian refugees and exiles, felt abandoned by the PLO, whose jurisdiction began to narrow down to part of the people on part of the land for a temporary period of time, and only through the PNA.”17 This development contributed to the belief throughout the diaspora that its rights and concerns were no longer a priority to the Palestinian leadership. The sections below examine the traditional role played by the PLO in foreign affairs and diaspora relations, and how the shift in favor of the PNA took place.

The Early Fruits Secured by the PLO Diplomatic Corps

Very early on, the PLO began establishing representative offices in foreign capitals as a way to build international support for Palestinian self-determination and rights, in addition to serving diaspora interests. The PLO Political Bureau was the central node of the PLO’s national liberation strategy. The first PLO mission outside of the Arab region was established in China in 1965,18 only a year after the PLO’s founding and before some Arab countries had formally recognized the organization as the representative of the Palestinian people. Though there was no significant Palestinian population residing in the country, the relationship was deemed important as a way to center the Palestinian national movement as an anti-imperialist and anti-colonialist struggle. The relationship resulted in the channeling of weapons and the provision of training to the PLO and its factions.19

Serious international advocacy and foreign relations work commenced after the UN and the Arab League recognized the PLO in 1974. Following the PNC’s adoption of Palestine’s “Declaration of Independence” in 1988 and the acceleration of the internationalization strategy, the PLO Political Bureau functioned as a quasi-ministry of foreign affairs representing the Palestinian people to governments around the world and in international organizations,20 with the aim of advancing the Palestinian political program of return and restoration of rights. By 1993, the PLO had offices in more than 100 countries. Yet unlike other countries, PLO offices and representatives abroad were still, first and foremost, representatives of a people and not of a state.

Today, the State of Palestine is recognized by 137 countries, and it hosts 42 foreign missions in Ramallah. There are also eight general consulates in Jerusalem that are accredited to the PNA.21 The existence of these consulates predates the creation of the state of Israel and their mandate covers Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza.

Growing Tensions in a Diplomatic Corps with Two Heads

For a decade following the establishment of the PNA in 1994, the PLO remained officially responsible for diplomacy and it retains, to this day, the sole official capacity to negotiate international agreements on behalf of the entire Palestinian people. The Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and Gaza Strip (Oslo II), signed in 1995, specifically prohibited the PNA from conducting foreign relations.22 Thus, if the PNA wished to open a diplomatic mission abroad or host a foreign mission in the OPT, Oslo II required that it relate to economic development.23 When the PNA engaged with the international community on projects or wished to accept donor assistance, the PLO had to sign on the PNA’s behalf.24

Despite the prohibitions contained in the interim agreement, the 2002 PNA Basic Law, the first quasi-constitution of the PNA, gave the president power over the selection of diplomats and the acceptance of credentials from foreign delegations.25 This might have been controversial except for the fact that the PLO chair at the time, Yasser Arafat, was also the PNA president. In addition, to avoid any appearance that it was running afoul of Oslo II, the PNA established the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation (MoPIC). For all intents and purposes, MoPIC operated like a foreign ministry working in parallel with the PLO Political Bureau. At meetings in foreign capitals, it was not unusual to have the heads of both PLO and PNA bodies representing Palestinian interests. Donor countries dealt with the PNA on the specifics of any development projects while the PLO signed the bilateral agreements.

Over time, tension developed between the PLO and PNA. According to Hanan Ashrawi, member of the PLO executive committee, “[a]fter the PLO came to the West Bank and Gaza to live under occupation, the [PNA] gained more and more authority because it became the financial address. And the PLO gradually weakened, diminished, and became what we call a line item in the budget of the [PNA] rather than the overall decision-maker.”26 She notes that the PNA’s “ministries began to encroach on [PLO departmental mandates]” with the tacit approval of the donor community. Ultimately, the PLO National Fund “found itself emptying out as the ‘liberation tax’ was no longer levied or transferred by the Arab governments, and all donations were earmarked for specific projects within the peacemaking agenda.”27 What prevented the PLO status and competencies from completely being overtaken by the PNA and its ministries was the fact that the chair of the PLO was also the president of the PNA.

In 2003, under pressure domestically, but more critically from the US and Israel,28 the Palestinian Legislative Council amended the PNA Basic Law to create an office of the prime minister. The executive branch was reorganized to strip certain powers from Arafat, the PNA president, who had raised the ire of the George W. Bush administration for attacks against Israelis during the 2nd Intifada. Prior to the changes,29 a unitary executive existed with the PNA president as the head of government. The 2003 amendments, however, established a dual-executive in which power was shared between the PNA’s president and its prime minister. This might have threatened PLO supremacy over the PNA except for the fact that the president of the PNA was made responsible for the appointment and dismissal of the prime minister,30 and retained authority over the appointment of diplomats and the credentialing of foreign delegations.31

The Abbas Era: Restructuring the Corps

With the election of Mahmoud Abbas as president in 2005, any trepidations about violating Oslo II prohibitions regarding the PNA conducting foreign relations were cast aside. The competencies of MoPIC were transferred to a newly-created PNA Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA). However, the PLO retained ultimate authority over the functioning of the ministry and international diplomacy in a number of important ways. First, only the PNA president, also sitting as PLO chair, may open or close a PLO office abroad.32 Second, because the prime minister is the president’s political appointee who serves at his pleasure, the president/PLO chair wields influence over the selection of cabinet members, including that of foreign minister. Third, as noted above, only the president/PLO chair, rather than the minister of foreign affairs or the prime minister, is officially responsible for appointing and terminating diplomats. Fourth, all laws, including those affecting the conduct of foreign relations, are promulgated by the president or must be passed by a supermajority. Obtaining a supermajority to force the president’s hand would be difficult to obtain without the president’s party – also the ruling party in the PLO – breaking ranks.

(The) PLO…retains, to this day, the sole official capacity to negotiate international agreements on behalf of the entire Palestinian people Share on XAs a final backstop in the event the PNA president and the PLO chair are not the same person, the Diplomatic Corps Law, discussed later in this chapter, specifically provides that promulgation of the law is under the authority of both the chair of the PLO and the president of the PNA,33 and that any PNA regulations implementing the Diplomatic Corps Law must be endorsed by both the president of the PNA and the chair of the PLO.34 In this way, any attempt to legislate powers over the conduct of foreign affairs away from the PLO could be stymied. Finally, only the PLO has internationally-recognized and legal authority to sign bilateral agreements and treaties; the PNA Basic Law does not give the executive branch power to sign agreements.

What becomes clear from the division of labor between the PNA and the PLO on matters affecting foreign relations, is that the linchpin to maintaining PLO supremacy lies in the chair of the PLO and the president of the PNA being the same person. In fact, the individual holding the chairmanship of the PLO and the presidency of the PNA have always been the same person. So long as the president is also sitting as PLO chairman, PLO primacy is ensured and the redundant foreign relations structures existing between the PNA and PLO are not in conflict.

This was born out to a degree in March 2006 when Hamas members Ismail Haniyeh and Mahmoud Zahar became prime minister and foreign minister of the PNA, respectively. No challenge to PLO authority over foreign relations was presented because Mahmoud Abbas, as PNA president and chair of the PLO, maintained authority over international relations and diplomatic engagements pursuant to the governing law of the PNA.

Suspending the Activity of the PLO Political Bureau

Following the creation of MoFA in 2005, PNA Foreign Minister Nasser Alkidwa advanced reforms meant to “integrate the performance” of the PLO’s Political Bureau with the PNA Ministry of Foreign Affairs.35 The preamble of the Diplomatic Corps Law, which Alkidwa championed, provides that nothing within the new law infringes on the ultimate authority of the PLO over foreign relations. However, the Political Bureau’s operations and competencies were effectively suspended and placed under the direct chairmanship of the PLO, leaving more operational room for the PNA Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Documentation of the effective demise of the PLO Political Bureau is not readily available and, in fact, PLO and PNA officials consulted for this study either did not know that the Political Bureau still existed or were hard-pressed to identify who led the shell department. That it no longer functions is suggested by the fact that following the last PLO Executive Committee elections held in 2018, and in which Mahmoud Abbas was reelected chair and president of the State of Palestine, a reshuffling of portfolios between committee members ensued. Wafa News Agency, which is associated with the PNA and the PLO, listed all the PLO departments and their new executive committee heads but made no mention of the existence of the Political Bureau.36 However, the PLO website does list the Political Bureau among the other PLO departments, although there is no reference to any executive member leading it. The focus on the professionalization of the ministry and the premium placed on modeling the attributes of an independent state came at the cost of PLO pillars of unity, mobilization, and liberation. Moreover, maintaining decision-making authority so that it could “slide between the PLO and the [PNA]” resulted in vitiating “institutional mechanisms of accountability.”

Virtually all the responsibilities of the Political Bureau relating to the conduct of foreign relations, including representing Palestine abroad, overseeing the work of the missions, and attending to the interests of and strengthening connections with the diaspora, became PNA-MoFA functions.37 The important tasks of formulating and implementing foreign policy and appointing diplomats38 were left to the PNA president/PLO chairman.39 Despite the shift in the conduct of foreign relations to the PNA, which financed embassies abroad, embassies and missions are all deemed PLO offices and are intended to receive funding from the Palestine National Fund.40 And yet, as Hanan Ashrawi notes, “[w]e have an administration in the PLO that is next to powerless because it has become only a duplicate of the [PNA], instead of being the main address to go to when dealing with Palestinians wherever they may be.”41

Additional PLO Bodies with Foreign Affairs/Diaspora Capacities

There are currently at least six departments of the PLO with duties that include foreign relations, or that share in the work of advancing diaspora interests and expatriate affairs. Those relevant to this study include the Political Bureau (effectively under the chair of the PLO), Negotiations Affairs, Diplomacy and Public Policy, International Relations, Expatriate Affairs, and Refugee Affairs. From time to time, the chair of the PLO and president of the PNA may also establish ad hoc bodies, or call on the Fatah International Relations Commission to conduct foreign relations, or engage with the diaspora and civil society abroad. The table in Annex 3 sets out those who had responsibilities for foreign affairs at different times, although many of the departments were inactive for some periods as there were no PNC meetings to redistribute and reassign files.

The responsibilities of the largely defunct PLO Political Bureau include representing the organization before international bodies, taking care of the interests of the Palestinian diaspora, and concluding international agreements and treaties – all duties that the PNA foreign ministry ascribes to itself with the notable exception of concluding international agreements. The department is also responsible for implementing the political program of the PLO.

The Negotiations Affairs Department (NAD) is responsible for following up on implementation of agreements. More broadly, the office is engaged in international diplomacy related to PLO negotiating positions, including with respect to refugee rights and diaspora claims. The head of the office frequently accompanies the chair of the PLO abroad.

The premium placed on modeling the attributes of an independent state came at the cost of PLO pillars of unity, mobilization, and liberation Share on XThe departments of Diplomacy and Public Policy (DPPD) and International Relations both engage with civil society actors at various levels on the PLO political platform. The DPPD also provides messaging and talking points directly to PLO offices abroad towards advancing the PLO political program of a two-state solution, and advocacy around respect for Palestinian rights and sovereignty.

The Expatriate Affairs (EAD) and Refugee Affairs (RAD) departments both serve diaspora communities. The EAD engages with Palestinians in countries outside of the areas of operation of the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA). RAD serves Palestinians where UNRWA operates, including in the OPT, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. The EAD and RAD coordinate their work.

Because of PLO/PNA redundancy with respect to foreign relations competencies, when the representatives of PLO departments, ad hoc committees, or the Fatah International Relations Commission are sent abroad, it may be unclear which entity, the PLO or the PNA, is coordinating the mission. On occasion, PLO official travel may be coordinated by the specific PLO departments directly with the relevant embassies and missions without involvement of the PNA-MoFA.

Chapter 3: The Functioning of the Diplomatic Corps

To understand the dynamics and challenges of the diplomatic corps, it is important to understand how the representative offices are funded, how appointments and staffing decisions are made, who manages operations, and how portfolios are distributed to offices. This chapter draws on interviews with various missions, as well as present and former diplomats and MoFA staff, and with diaspora Palestinians.

Overall, the interviews reveal a gap between those who still consider themselves PLO representatives charged with representation and liberation, and newer appointees who function more like bureaucrats. There was also confusion about the way in which appointments were made and a sense that favoritism (wasta) sometimes came into play. The missions also faced the difficulties of dealing with the Fatah-Hamas split, and the human rights violations stemming from security coordination with Israel. Most importantly, many felt they lacked political direction from Ramallah due to being trapped in the Oslo framework, even as Israel was relentlessly colonizing the land and destroying the statehood project.

Resourcing the Corps

The source of funding for Palestine’s diplomatic corps is intended to be the Palestine National Fund, the PLO’s sovereign fund, which is currently under the supervision of the PLO chairman. In pre-Oslo days, when PLO members faced visa restrictions in certain countries, the missions depended on the diaspora for their staffing, as well as to cover their costs. Even after MoFA was established and appointments began to be made from Ramallah, some missions still relied on the diaspora for part of their resources. Contrary to reports, the Fund still exists and is funded according to a reliable source; a few ambassadors who used to be PLO staff get paid from the Fund, while the rest get paid by the Ministry of Finance.

The best resourced missions are in general the ones that deal with multilateral affairs at the UN, the EU or the Hague, or are based in a major country capital. A mission’s numbers can quickly expand to respond to specific needs; for example, Palestine’s chairmanship of the G77 (group of developing countries) at the UN in New York in 2018, or at the Hague to handle the International Criminal Court file. In the year before its closure in 2018, the mission in Washington, DC, was quickly expanded and resourced to engage with the incoming Trump administration.

On the other hand, some missions are bloated well beyond their needs and host diplomats well past retirement age. This is in part due to personal connections, but in other cases it is reportedly due to the need to find homes for PLO members who sacrificed for the cause but were not allowed back into Palestine. Some missions are large due to the extensive protocol duties and consular services they have to provide, such as the mission in Amman.

Staffing: Activists vs. Civil Servants

As noted above, the PNA president hires and fires diplomats, while staff are hired and promoted by the PNA Foreign Minister.42 MoFA has a clear staffing chart for each embassy but it is not necessarily reflected in the actual situation on the ground. While some diplomats consider themselves PNA diplomats, others have clear allegiance to the PLO. According to interviewees, when MoFA began to take over the functions of the PLO Political Bureau after 2005, differences arose between the diplomats and staff who were from the revolutionary and activist period versus those civil servants and bureaucrats who received their commissions from the PNA.

The interviews revealed a lack of clarity amongst the corps as to how diplomats are appointed. A nominations committee that includes the president’s office, the Palestinian National Fund, and MoFA reportedly makes the final decision. In the past, there was little training and many of the diplomats developed skills while on the job, emulating more established diplomats. However, this is changing among younger diplomats who are receiving more structured training.

The shrinking space for Palestinian rights advocacy due in large part to the conflation of criticism of Israel with anti-Semitism is having an impact on Palestinian diplomacy Share on XIn recent years, MoFA has been seen as a prestigious place to work, and the PLO and Fatah elite are said to be keen to place their sons and daughters there. Some managers have complained that this practice complicates their task, as personal connections enable staff to bypass their decisions. What is clear is that, as in other bureaucracies around the world, a bad high-level appointment can make or break a mission. Some missions in countries key to the Palestinian cause have gone from a high degree of effectiveness to bitter infighting, almost disappearing from the scene. While there are a number of effective missions, there are also some where the head diplomats simply treat the posting as a sinecure.

Palestinian Representation Abroad: Successes and Challenges

Unlike traditional embassies and missions, the diplomatic corps is supposed to advance the PLO political program in support of the two-state solution, as well to as serve as the sole representative of the Palestinian people wherever they are. However, as discussed above, the devolution of most PLO responsibilities to the PNA, including oversight and management of diplomatic missions, has meant that the missions look more like those of a proto-state, with sections for cultural exchange, trade relations, and consular affairs, rather than those that might support a liberation movement.

A successful Palestinian mission is perceived as one that is able to both increase the value of bilateral relations in the country of posting, and strengthen its commitment to Palestinian sovereignty and rights. For example, according to one diplomat, their missions set up regular meetings between Palestinian ministers and their counterparts, as well as with parliamentary committees on a systematic basis. In addition to tackling policy issues in foreign affairs, such meetings also covered education, agriculture, and trade, among other spheres. The goal, as this diplomat put it, “was to empower our counterparts on the question of Palestine, to let them do their job, but to give them the tools and content to do it better.” This diplomat was able to do this work because they knew the right interlocutors in Ramallah to call, a line of communication that might not be available to other diplomats.

Among the challenges faced by diplomats, the division between Fatah and Hamas looms large. This has, among other problems, reportedly created unwanted opportunities for outside parties such as the UN to get involved “on behalf of” the Palestinians. Another issue is the lack of direction from Ramallah in some cases, as well as tendency to micromanage in others. The diplomats also struggle to address the PNA’s recorded human rights violations, which has been greatly detrimental to the broader cause. In addition, there is a feeling among diplomats that their capacities have been overstretched, in particular given new treaty obligations after the 2012 bid for statehood.

Another major challenge facing Palestinian diplomats is to monitor the role played by Israel in the country both at the official and community level. That is, Israeli diplomats constantly try to upgrade their relations while undermining those of the Palestinians. The shrinking space for Palestinian rights advocacy due in large part to the conflation of criticism of Israel with anti-Semitism is having an impact on Palestinian diplomacy. In some countries, it is increasingly difficult for the diplomats to do their job because they are cold-shouldered by the country government for fear of being seen as anti-Israel, even in countries that are committed to upholding the main UN resolutions on Palestinian rights.

The PLO/PNA’s continued adherence to the Oslo framework and the failure of national reconciliation pose major challenges to all advocates of Palestinian rights, including Palestinian civil society, the Palestine solidarity movement, and Palestinian diplomats. With Israel (the PLO’s purported negotiating partner) rapidly entrenching and consolidating its control over the West Bank, including East Jerusalem (formally annexed in 1980), and with Israel maintaining its tight siege on Gaza, the PLO’s political program based as it is on a two-state solution has been called into question. The split between the PLO’s ruling party, Fatah, and the Islamist party Hamas, contributes to the lack of a unified strategy and message that inhibits greater mobilization and coordination among the diaspora, and between the diaspora and the mission.

The lack of movement on Palestinian rights also contributes to the perception in the diaspora that diplomats and the PLO/PNA are out of touch with the Palestinian people and have no vision. In reality, diplomats, like the Palestinian people, express frustration with the current state of affairs and lament the lack of strategy to deal with the challenges facing the national movement that were set out in Chapter 2. The one notable exception when the diaspora and the missions felt a sense of shared purpose and common strategy was during Palestine’s bid to become a member state of the UN, which will be discussed in Chapter 4. A former senior diplomat summed it up: “The core of the problem remains the lack of political direction, of leadership and of any vision or strategy. There is only so much the missions abroad can do, considering the central leadership has no credibility or plan.”

Relations with the Diaspora: More Consular than Political

In countries with Palestinian diaspora populations, embassies and missions have generally designated staff responsible for community relations and outreach. When the diaspora engages with PLO embassies and missions, it is likely to concern consular matters (such as certifying marriages, births and deaths, or authenticating documents), or when they experience some difficulty with the host country. At the same time, depending on the diplomat’s credibility with the Palestinian community as well as her/his willingness to be proactive, the diaspora may engage on matters impacting their national rights or representation within the PLO. The diaspora may also reach out to the missions and invite the ambassador to speak at events, or the diplomats may seek out engagements with community groups and leading local activists to build relations with the community.

As discussed previously, the Oslo Accords adversely impacted the relationship between the diaspora and the PLO and its representatives (see also Chapter 5). Many diaspora Palestinians do not have a clear sense of the work of the PLO’s mission, and tend to dismiss the entire corps because of their disappointment in and frustration with the failure of the national project, lack of effective leadership, prolonged rule by diktat in the homeland, and lack of communication and engagement with communities abroad.

The core of the problem remains the lack of political direction, of leadership, and of any vision or strategy. There is only so much the missions abroad can do, considering the central leadership has no credibility or plan Share on XThe schism between Fatah and Hamas has of course been reflected in the diaspora. Hamas and other Islamist groups are largely alienated from the official missions by virtue of the fact that Hamas is not a member of the PLO and that many mission heads are close to Fatah. In countries where they are able to do so, the Islamist groups have their own community or civil society organizations. In one European country for instance, there are three Palestinian community associations, one supported by Fatah, one by the Fatah break-away group headed by Mohammad Dahlan, and one by Hamas.

The issues raised in this chapter are intended to provide some background to the discussion of the three issues selected for more in-depth analysis in Chapter 4. It is worth concluding this section with a reflection from a seasoned diplomat: “For sure the parallel system between the PLO and the [PNA] does not work well, but it is possible to deal with them as different parts of the same body. The [PNA] provides education, healthcare, and other services, and the PLO undertakes the political part, the advocacy, and the protection of rights. But what we need is more leadership and strategy.”

Chapter 4: The Diplomatic Corps’ Engagement with the Diaspora

In order to study the extent of the diplomatic corps’ engagement with the diaspora, as well as its ability to represent the Palestinian national project, we selected three events that have marked the recent political history of the PLO/PNA. The first was an initiative fully planned and executed by the PLO at the international level, the “statehood bid” of 2010 to 2012 that resulted in upgrading Palestine’s status at the UN from observer to non-member state. The second was the Palestinian response to the major external threat posed by US president Donald Trump’s decision to the move the US embassy to Jerusalem in 2017, in violation of international law. And the third dealt with an internal challenge, the state of the PLO’s representativeness of the Palestinian people as displayed by the PNC elections in 2018 – elections that were held despite the growing disaffection with the PLO/PNA leadership due to its treatment of Gaza, the unresolved Fatah-Hamas split, and the persistent effort to cling to the Oslo Accords and negotiations despite their failure to secure Palestinian rights.

We interviewed Palestinian diplomats and former diplomats, as well as members of the Palestinian diaspora and representatives of solidarity groups in each of the eight countries selected for our study. Based on our findings, the statehood bid showed how effective the PLO could be when the corps and the diaspora worked together toward the same ends, with clear instructions and messaging. As for the US decision to move its embassy to Jerusalem, the limited information we were able to collect about the response of the PLO, diaspora, and solidarity groups to this threat suggests that the issue was dealt with as a matter for the state system. Finally, the detailed responses we gathered about the PNC election process in 2018 indicated how broken the system of Palestinian representation had become.

The Statehood Bid: PLO-Diaspora Engagement for National Objectives

While Palestinians might disagree about the value-added of the statehood bid, it was clearly a successfully orchestrated diplomatic endeavor that also engaged the diaspora. Within the PLO and PNA, the bid was understood as an initiative to establish wide international political recognition for the State of Palestine on land occupied by Israel after June 5, 1967. Some of those involved dated the effort as early as the 1988 PNC resolution declaring Palestine’s independence. Others ascribed it to the 1999 Berlin Declaration of the European Council which spoke of the “option” of a Palestinian state as part of the final status talks. Still others asserted that it began as a fallback initiative in case the 2007-2008 Annapolis Conference failed to conclude with an agreement on final status issues.

The period examined in this study encompassed the two years between the fall of 2010 and the fall of 2012, beginning with the end of the Obama administration’s failed attempt to re-start Palestinian-Israeli direct talks, and ending with the General Assembly’s recognition of Palestine as a non-member state of the UN. It was in 2010 that the “Palestine-194” campaign went into full swing as a PLO initiative to secure the State of Palestine as the 194th member state of the UN, and to obtain additional bilateral recognition of Palestine with those states that had yet to do so. The underlying aim was two-fold: to advance the PLO’s negotiating position vis-a-vis Israel in peace talks by preserving international consensus around the 1967 Green Line, and as a prerequisite to accessing certain international mechanisms for Israeli accountability, including at the ICC for Palestinian victims of Israeli war crimes. The State of Palestine had already submitted a declaration in 2009 accepting ICC jurisdiction.

The height of the PLO’s efforts came when Mahmoud Abbas submitted an application for Palestine to join the UN as a full member on September 23, 2011, during the opening of the UN General Assembly. Admission required a favorable recommendation to the General Assembly from the Security Council, where the US holds veto power. Anticipating that the US would thwart such a recommendation, the PLO prepared a fallback strategy to build support for a General Assembly resolution upgrading Palestine’s status at the UN from an entity to a non-member observer state.

While deliberations were ongoing in the Council’s Admissions Committee, the PLO sought entry to other specialized agencies of the UN, including UNESCO.43 That body presented an important test for the level of support for Palestine’s statehood initiative as admission required a two-third majority vote at the General Conference made up of 195 countries, including those western European countries that were important trading partners for Israel, and that had yet to extend bilateral recognition to Palestine. Not only would a favorable vote at UNESCO put pressure on states deliberating Palestinian statehood in the Security Council Admissions Committee, it could also provide important evidence to the ICC that Palestine was a state for purposes of the Court, assuming jurisdiction over war crimes allegations committed by Israeli individuals in the OPT. Only states may accept ICC jurisdiction under the body’s governing law, the Rome Statute.44

UNESCO’s General Conference voted to admit Palestine on October 31, 2011, with 107 in favor, 14 against, and 52 abstentions. According to one advisor to PNA President Mahmoud Abbas, the vote was not only “a historic moment … en route to full recognition of Palestinian independence and self-determination,” it was also “a foundation stone” for efforts at the Security Council and other international organizations, and “a manifestation of ability of the international community to defy occupation and practically work towards ending it.”

No one thought a UN vote would liberate Palestine, but at least we started thinking in a direction that would move them away from the Oslo process Share on XLess than two weeks later, the UN Security Council Admissions Committee failed to recommend that Palestine be admitted to the UN as a full member state. Rather than force a vote in the Council which would have been futile, the PLO/PNA redoubled its efforts in preparation for a UN General Assembly resolution recognizing Palestine on the pre-June 5, 1967 Green Line, and upgrading its status at the UN from observer entity to a non-member observer state. Efforts were buoyed by the prosecutor at the ICC who decided in 2012 that he did not have the competency to decide whether Palestine was a state for purposes of establishing ICC jurisdiction. Instead, he signaled that the UN General Assembly was the proper body for that determination. The General Assembly spoke on November 29, 2012, the International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People, by admitting Palestine as an observer state.45