Executive Summary

The practice of mapping in Palestine-Israel has long been an exercise in power, imperialism, and dispossession. From the British Mandate to the present day, Zionist (later Israeli) cartographers have used maps to obfuscate and eradicate physical, geographic, and social markers of Palestinians’ connections to, and possession of, the land.

During the British Mandate, the colonial forces produced an array of detailed surveys for military, political, social, and economic planning. The geographic distribution and activity of Palestine’s indigenous Arab inhabitants were rarely depicted on the maps. However, the geographic language was almost entirely comprised of transliterated Arabic names.

In the wake of the First Zionist Congress in Basel in 1897 and the first Aliyah, or wave of European Jewish immigration from 1881 to 1903, Zionist maps began to proliferate, many featuring topographic and religious markers designed to redraw the map in the image of a proposed Zionist state.

After the Nakba of 1948, the new state of Israel set out to transform the national map from Arabic to Hebrew as a way of Zionist nation-building. The Hebrew map continues to be an exercise in state formation, a living document of Zionist colonization where Zionist ideology is folded into the spatial practices of the Israeli state.

Today, legislation such as the Kyl-Bingaman Amendment (KBA), which restricts the availability of high-resolution satellite imagery by preventing US satellite operators and retailers from selling or disseminating images of Palestine-Israel at a resolution higher than that available on the non-US market, as well as the complicity of technology firms in privileging Israeli spatial control at the expense of Palestinians – such as how Google Maps routes are designed for Israelis and illegal Israeli settlers – represent a missed opportunity to use technological advancements to democratize mapping.

However, technology can serve as a tool to tangibly imagine the right of return. Detailed historical maps and uncensored, high-resolution images, for instance, allow Palestinians to catalogue the remnants of villages and towns destroyed during the Nakba. Such images not only provide substantial proof of the ongoing colonial encroachment into Palestinian land, but allow Palestinians to actively imagine an alternative reality.

For Palestinians living under martial law in the Occupied Palestinian Territory or under siege in the Gaza Strip, despite technology creating an opening for democratizing spatial practices, mainstream mapping applications fail to account for the walled-off reality on the ground and the restrictions and repercussions it has on Palestinian movement. Yet Palestinians and allies continue to subvert and resist colonial maps through counter-maps.

There are some other concrete steps forward:

- As recommended by 7amleh, the Arab Center for Social Media Advancement, Palestine should be named properly on Google Maps, in line with the UN General Assembly Resolution of November 2012.

- According to Resolution 181 of the UN General Assembly, the international status of Jerusalem should be correctly displayed on Google Maps. Google must also identify and correctly label illegal Israeli settlements on occupied land, according to Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention and Article 55 of the Hague Regulations.

- Google should clearly distinguish areas A, B, and C in the West Bank and account for all movement restrictions and restricted streets.

- Google should locate “unrecognized” Palestinian villages within Israel as well as Palestinian villages in Area C.

- The United States should dispose of the KBA, leveling the commercial playing field between US and non-US imagery providers. This would allow satellite operators to share high-resolution images of Palestine-Israel on widely-used open-access platforms. It would also enable archaeologists, researchers, and humanitarians to accurately document changes on the ground and allow for better accountability of the Israeli occupation.

- Palestinian civil society should encourage and promote the active use of counter-maps as an alternative to incomplete contemporary maps. Simultaneously, Palestinian civil society and allies should focus their efforts on pressuring (a) the US government to abolish the KBA and (b) Google to make the changes outlined above.

Overview

The practice of mapping in Palestine-Israel has long been an exercise in power, imperialism, and dispossession. From the British Mandate to the present day, Zionist (later Israeli) cartographers have used maps to obfuscate and eradicate physical, geographic, and social markers of Palestinians’ connections to, and possession of, the land.1

The advent of Global Positioning System (GPS) technology, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) software, and increasing numbers of remote sensing satellites over the past few decades enabled the accurate and comprehensive mapping of the Mandate territory of Palestine. Instead, publishers of satellite imagery, including Google, continue to erode the presence of Palestine either by publishing low-resolution imagery, suggesting incorrect route options for Palestinians, labeling inaccurate and/or Hebraicized place names, or simply leaving territories inhabited by Palestinians blank – a pixelated terra nullius.

This policy brief examines the varied ways that Palestinians have been excluded from maps of their own land, from the start of the British Mandate to the present day. It argues that poorly mapped localities alter the way that Palestinians understand space and alienate them from their homeland. It also explores alternative, subversive maps as ways of recognizing the past, appraising the present, and imagining the future. It concludes that maps, though intricately linked to both British and Israeli colonialism, and consistently used as vehicles of erasure, can be reclaimed as expressions of geographic imagination and a means of resistance.

Colonial Cartography

Despite their claims to a mathematical realism, modern maps do not simply reflect reality: They create and embed a particular perception of the earth we live on. Lines drawn on a map separate countries from oceans and each other. The area between the lines represents constructed socio-political entities of sovereign space: nation states. Despite the process of state formation and disintegration in places like Palestine, Sudan, and Tibet, nation states are accepted in the international order as fixed entities. In contemporary map projections, which represent Earth’s three-dimensional surface on a two-dimensional plane, nation states are portrayed as definitive, objective, and self-evident markers of political reality – a façade reinforced by users who interact with political maps as a perfect, scaled portrayal of space. Over the past few decades, globe projections, especially the ubiquitous Mercator cylindrical projection, have been criticized for their Eurocentrism. The standard world map places the northern hemisphere on top, with Europe firmly in the center. The Mercator projection, in particular, distorts the relative size of the continents, dramatically shrinking Africa and South America and making Europe, North America, Australia, and particularly Greenland appear much larger than they actually are. The world maps of today are still very much colonial and nationalist enterprises reflecting predominantly Western acquisition and control of territory. Maps intended as navigational tools quickly evolved into the means by which the Earth and its assets were artificially divided amongst the colonial powers. It was only by containing diversity in single, bounded areas that control could be first exercised, and then consolidated and maintained. As Paul Carter argues, maps were “the hieroglyph of imperialism’s intent to separate and classify the spread of the earth’s surface in order to occupy its territories and command its resources.”

Today’s world maps are still colonial and nationalist enterprises reflecting predominantly Western acquisition and control of territory Share on XThis is consistent with maps of the modern Middle East drawn during and shortly after the First World War by British and French imperial powers, epitomized by the Sykes-Picot agreement in 1917 and the San Remo conference in 1920. The new maps composed by European actors transformed a region formerly comprised of territorially fluid Ottoman administrative units into a disjointed set of territories marked by long, arrow-straight lines from which sprung the new protectorates of Iraq, Transjordan, Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria. These nations were endowed with newly-minted imperial monarchs and nested within a paternalistic mandate system.

British Colonial Maps in Mandatory Palestine

In Culture and Imperialism, Edward Said explains the “struggle over geography” as one “not only about soldiers and cannons but also about ideas, about forms, about images and imaginings.” In this vein, the latter half of the nineteenth century saw a flurry of orientalist explorations of Palestine by Europeans conducting historical, linguistic, geographic, and archaeological studies and surveys, especially in areas of biblical and religious significance. In contrast to medieval and early-modern religious maps typically featuring mythical creatures and biblical place names, modern European explorers-cum-cartographers based claims to the realism and accuracy of their maps on the “scientific” methods underlying them. While the British Mandate over Palestine came into full effect in 1922, the British government had been readying itself for domination over Palestine decades prior. From 1871-1877, Britain’s Palestine Exploration Fund carried out an extensive survey of western Palestine. Although the expedition was led by religious and academic figures, there was direct involvement from the government which, it is argued, used these benign associations “as a front to…collect intelligence on the region.” The survey produced was by far the most precise and technologically sophisticated to date, and was used as a military planning aid during the British invasion of Palestine in the First World War. Its scope focused on the territory between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, closely resembling the borders of British Mandate Palestine 50 years later.

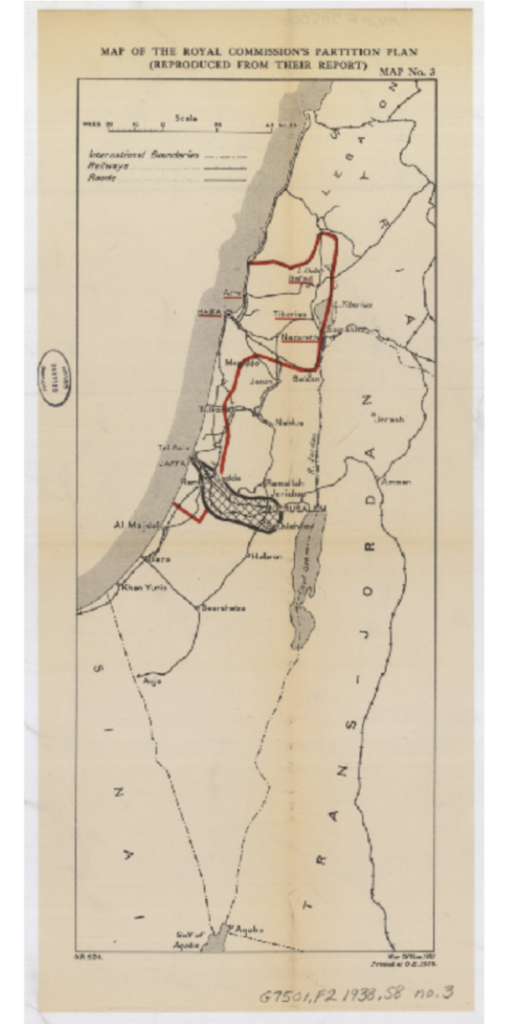

Figure 1: The Peel Commission Partition Plan, 1937

During the British Mandate, the colonial forces produced an array of detailed surveys for military, political, social, and economic planning. The geographic distribution and activity of Palestine’s indigenous Arab inhabitants were rarely depicted on the maps. For instance, following the Great Arab Revolt (1936-39) in Palestine, the Peel Commission – tasked with finding a “solution” to the unrest and for the first time recommending partitioning Palestine in 1937 – used maps to demonstrate different possible Arab/Jewish partition plans ignoring the demographic realities on the ground (Figure 1).

The geographic language of British maps was almost entirely comprised of transliterated Arabic names, especially in places significant to the Christian tradition. The British Mandatory Survey of Palestine prepared in the 1940s became the canonical map of Palestine depicted as a single administrative unit. In it, thousands of Arabic place names were used.2 This became a great source of tension with the Zionist leadership, who insisted on the inclusion of Hebrew place names (wherever they existed) alongside Arabic and/or English designations in official government publications. The elimination of Arabic names and their replacement with Hebrew names became the cornerstone of Zionist spatial policy after the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, and continues today.

Early Zionist Cartography

In the wake of the First Zionist Congress in Basel in 1897 and the first Aliyah, or wave of European Jewish immigration from 1881 to 1903, Zionist maps began to proliferate, many featuring topographic and religious markers designed to redraw the map in the image of a proposed Zionist state. In particular, the Keren Hayesod, the fundraising arm of the Zionist movement, and the Jewish National Fund (JNF), an organization dedicated to the acquisition and development of Palestinian land for exclusive Jewish settlement, used maps to advance the Zionist colonization of Palestine.

Figure 2: Keren Hayesod map, 1932

Figure 2 is a 1932 map that the Keren Hayesod used as a fundraising tool to solicit donations from the Jewish-American community. One side of the document boasts of the Keren Hayesod’s achievements, while the map on the reverse side depicts the Mediterranean coast and northern region in red to indicate what the key designates as “Jewish lands.” Jerusalem is marked by the Star of David, while Palestinian localities are limited to a handful of urban centers. The native population is depicted, in a clear example of orientalism, as four sketched figures riding on camelback superimposed over the desert. Other figures show hardworking Jewish laborers drawn beside new agricultural and industrial centers. This juxtaposition illustrates Ella Shohat’s claim that European Zionists understood themselves as the ones to “make history,” whilst the natives formed an “almost inorganic background.”

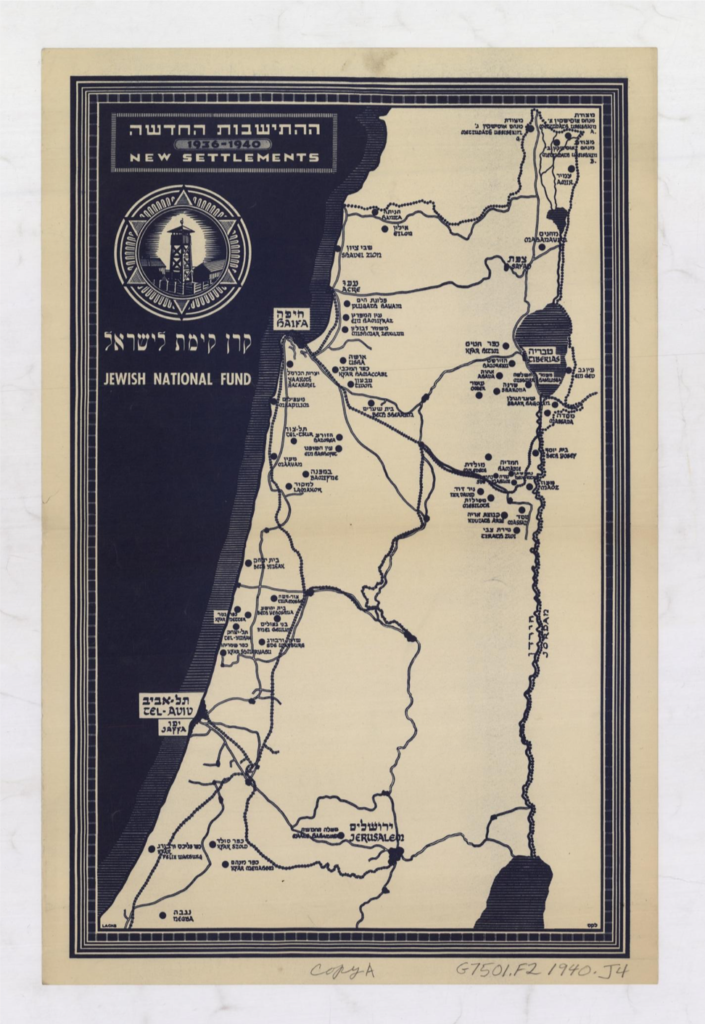

Figure 3 is a JNF map (one of many) depicting new Jewish settlements between 1936 and 1940 in Hebrew. The names of the pre-state settlements were selected according to Biblical/Talmudic references or in commemoration of Zionist figures, making biblical Jewish history integral to the geography of modern Zionist expansionism. The settlement patterns in coastal and northern regions resemble those in Figure 2 and again the map features almost no Palestinian localities. The thriving commercial and agricultural Palestinian centers in what is today referred to as the West Bank are vacant, with only Jerusalem and the Jerusalem-Jericho road indicating any life at all.

Figure 3: Jewish National Fund map, ~1940

The erasure of the indigenous Palestinian people from the land reinforced the infamous Zionist adage that Palestine was “a land without a people for a people without a land.” This was, of course, a fallacy. Palestine, by the end of the nineteenth century, had a population of about 600,000 and was agriculturally active and economically and politically engaged.

Creating the Hebrew Map

In the wake of the Nakba of 1948 – denoting the loss of the Palestinian homeland and the displacement of 750,000 Palestinians from their homes – the new state of Israel set out to transform the national map from Arabic to Hebrew as a way of Zionist nation-building. Hebrew names were affixed to all geographic features in order to fuse biblical Jewish history with territorial control. The ultimate goal was to render Hebrew the only language through which to understand the landscape, thereby erasing the experiences and histories of the original inhabitants. Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, understood that place names were not simply a linguistic choice but an expression of power relations, and in July 1949 he assembled a commission to “determine Hebrew names to all the places, mountains, valleys, springs, roads and the like in the area of the Negev.” Over an eight-month period, the Beer Sheba region in the south was transformed into the “Negev,” culminating in August 1950 with a Hebrew map of the area. This was done by gathering place names from British colonial maps, translating the existing Arabic names, and situating these names in a biblical/religious and historical context to lend them authenticity. Hebraicizing the Beer Sheba region was seen as an essential test case for strengthening Israeli sovereignty over the newly acquired territory. Ben-Gurion praised the commission:

You have banished the shame of foreignness and of an alien language from half of Israeli territory and completed the job begun by the Israeli Defense Forces: to liberate the Negev from foreign rule. I hope that you will continue your work until you will redeem the entire area of the Land of Israel from the rule of foreign language.

The Hebraicization of place names subsequently became a state-sponsored national project. The Governmental Names Commission was established in March 1951 to give “Hebrew names to all places with Arabic names” and assign names for newly-created places. A decade after the state was created, the commission had assigned some 3,000 new names whereasthe names of Palestinian villages were simultaneously removed from Israel’s official index. As the commission’s 1958 report stated: “As long as the names did not appear in maps, they cannot take possession in life.” Meanwhile Ben-Gurion and the commission drilled Hebrew place names into official and unofficial institutions, agencies, and organizations. The Israeli army was ordered to use and distribute the new names, and the Ministry of Education was instructed to affirm Hebrew names and discard Arabic ones in schools. The Hebrew names were also disseminated and promoted in various governmental agencies, such as the Public Works Department, as well as in media outlets. The Hebraicization of the map displays a paradoxical attitude toward the Arabic language. On the one hand, it was accused of being foreign and alien, while on the other, it was the undisputed marker of authenticity and indigeneity. Palestinians possessed an intimate relationship to and knowledge of the landscape due to their continued presence over centuries. Contemporary Arabic place names were therefore assumed to have preserved the ancient names and traditions of Biblical times. For the commission, they became a clue to the past, affecting how Hebrew names were chosen. The commission either directly translated the meaning of Arabic names or, if their sounds were similar to Hebrew, appropriated them with a Hebrew inflection. The Hebrew map is still being crafted beyond the Green Line (delineating the Armistice Line of 1949) in East Jerusalem, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and the occupied Syrian Golan. Despite the fact that settlements are in violation of Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, the Government Names Commission has determined monikers for illegal Jewish settlements since 1967 to ensure linguistic uniformity on both sides of the Green Line. This demonstrates the ongoing nature of the Israeli state-building project – a state that, since its inception, has sought to control the maximum amount of land with the minimum number of Palestinians.Today, maps of the West Bank portray a dizzying patchwork of political and military designations according to Oslo Accords-determined Areas A, B, and C. These are often superimposed with illegal settlements and Palestinian built-up areas as well as checkpoints and roadblocks. Maps produced by monitoring bodies such as the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs are multi-layered, convoluted, and often illegible to the layperson. Crucially, any map of the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT) is out of date almost as soon as it is issued, as Jewish-Israeli settlements increase, Palestinian lands are truncated, and barriers are expanded, collapsed, or relocated. While maps within the Green Line regularly portray Israel as a fixed and homogeneous geography entity, maps beyond it depict an unstable and unfinished geographic reality where Israel continues to manipulate, control, and annex land. Thus, the Hebrew map was, and continues to be, an exercise in state formation, a living document of Zionist colonization where Zionist ideology is folded into the spatial practices of the Israeli state. This is what Palestinian cartographer Salman Abu Sitta means when he says Palestinians have been “abolished from the map.”

Technology as a Missed Opportunity

Technological advances over the past two decades have radically altered how humans interact with space. Since the 1999 launch of the IKONOS satellite, the general public has been able to access detailed images of Earth, a privilege previously reserved for governments. The rapid democratization and proliferation of satellite imagery, both open source and commercial, including Google Earth, DigitalGlobe’s WorldView, and Planet, heralded a new era. High-resolution geospatial data is used for advocacy, accountability, and analysis in a myriad of different causes, from tracking climate breakdown to monitoring global poverty and conflict to facilitating disaster relief and preserving cultural heritage. Groups like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch as well as media outletsuse geospatial data to witness and assess human rights abuses internationally.

The Hebrew map was, and continues to be, an exercise in state formation, a living document of Zionist colonization where Zionist ideology is folded into the spatial practices of the Israeli state Share on XSatellite imagery is often portrayed as objective, precise, and authoritative – and is thus generally depoliticized and rarely challenged. However, just like printed maps, satellite images (and the uses to which they are put) are still vulnerable to cartographers’ social and political biases that can hinder their potentially progressive impact. This is especially apparent in the case of Google and its thorny relationship with Palestine.

A 2018 report by 7amleh, the Arab Center for Social Media Advancement, argues that Google Maps serves the interests of the Israeli government, facilitating its attempts to shirk its responsibilities toward occupied populations under international human rights frameworks. The report highlights that Google Maps routes are designed “only for Israelis and illegal Israeli settlers and can be dangerous for Palestinians.” The software automatically calculates routes under the assumption that the user is an Israeli ID holder able to use Israeli-only roads, and neglects the hundreds of checkpoints, roadblocks, and barriers that curtail Palestinian freedom of movement.

Labeling and naming is likewise a matter of contention. Despite never having declared its borders, Google gives Israel a label and boundary as if it were an uncontested block of territory, with Jerusalem marked as its capital, ignoring its internationally recognized status. Meanwhile, many Palestinian localities are de-emphasized or altogether erased, including Bedouin villages that remain unrecognized by the Israeli state, as well as Palestinian villages within Israel-controlled Area C of the West Bank. Significantly, the West Bank and Gaza Strip (excluding illegal Israeli settlements) do not appear as part of any country or state, since Palestine is not labeled as such. Indeed, Google was engulfed in a firestorm in 2016 over a bug that removed the names West Bank and Gaza Strip from its map, prompting a petition entitled “Google: Put Palestine On Your Maps!,” which has accrued over 615,000 signatures.

Google’s emphasis on Israeli localities, illegal or otherwise, also applies to Google Street View, which covers most of Israel and its illegal settlements, as well as the Israeli-occupied Old City of Jerusalem. Conversely, much of Palestine remains unavailable to view, with the exception of the Palestinian cities of Jericho, Bethlehem, and Ramallah and a few places in the Gaza Strip.

Moreover, as a direct consequence of US government policy, Google Earth is legally required to restrict access to images of Palestine-Israel. Bipartisan legislation passed by the US House of Representatives in 1997 limits the quality of satellite imagery of Palestine-Israel available to the public through US-based platforms like Google Earth and Bing Maps. The Kyl-Bingaman Amendment (KBA) to the US National Defense Authorization Act restricts the availability of high-resolution satellite imagery by preventing satellite operators and retailers in the US from selling or disseminating images of Palestine-Israel at a resolution higher than that available on the non-US market. While the KBA only applies to US companies, the hegemony they hold in the commercial market for satellite imagery had, until very recently, elevated the legislation to de facto institutionalization globally, affecting the access of campaigners, monitoring bodies, and researchers worldwide.

Though the law was implemented under the pretense of protecting Israel’s security, it is better characterized as censorship since images of Palestine-Israel are limited to a resolution of two meters. As Fradley and Zerbini demonstrate, by deliberately blurring satellite images of Palestine-Israel, the KBA hinders the work of archaeologists, environmentalists, geographers, and humanitarians. Indeed, lower-resolution imagery impedes humanitarian efforts to document human rights violations, such as Israeli land grabs, home demolitions, and settlement activities, and undermines Palestinian claims to land. It also hinders the assessment of damage from conflict in dense, hard-to-reach areas such as the Gaza Strip, most recently during the Great March of Return beginning in March 2018.

Palestinians have directly challenged this censorship by actively obtaining their own aerial images at a higher resolution than those offered by Google through “do-it-yourself” techniques, such as by attaching digital cameras to kites or balloons. This method was used to document the construction of a six-lane highway that cut through the Palestinian neighborhood of Beit Safafa in Jerusalem and its effects on the local population.

Damaging legislation such as the KBA, as well as the complicity of technology firms in privileging Israeli spatial control at the expense of Palestinians, represent a missed opportunity to use technological advancements to democratize mapping. Instead, it has created a “ubiquitous mechanism of censorship.”

Decolonial and Counter-Mapping

Decolonizing maps is a process that involves acknowledging the experience of the colonial subjects (Palestinians) on the one hand, and documenting and exposing the colonial systems and structures (Zionist expansionism) on the other. Decolonization requires what David Harvey calls “the geographical imagination” – linking social imagination with a spatial-material consciousness. Since 1948, Palestinians have held on to the memory of destroyed homes and villages through the creation of atlases, maps, memoirs, art, books, oral histories, and websites. The right of return for Palestinian refugees and internally displaced people is not just a political solution but the first step in a process of decolonization. Return, as a “counterpoint to exile,” raises critical and practical questions such as: What does return look like? What do we build where? Who will build what?

The complicity of technology firms in privileging Israeli spatial control represents a missed opportunity to use technological advancements to democratize mapping Share on XWhile there is valid criticism that counter-maps reproduce and embed existing exclusionary territorial and spatial practices, ongoing counter-mapping efforts demonstrate how Palestinians and allies are creating a decolonized cartography beyond simply (re)asserting lines on an existing map. Rather, these efforts put personal and collective memories in spatial terms and incorporate them into a legal and political framework. Walid Khalidi’s 1992 tome All that Remains charts each destroyed Palestinian village with images and demographic information. Similarly, Salman Abu Sitta, founder of the Palestine Land Society, has drawn up a comprehensive plan for return using maps, highlighting that many destroyed villages have not been repopulated and can therefore accommodate the return of their peoples. Additionally, his Atlas of Palestine (2010) is a historical record of pre-Nakba Palestine, methodically laid out using aerial imagery at a scale of 1:25,000.

Technology can serve as a tool to tangibly imagine the right of return. Detailed historical maps and uncensored, high-resolution images allow Palestinians to catalogue the remnants of villages and towns destroyed during the Nakba. Such images not only provide substantial proof of the ongoing colonial encroachment into Palestinian land, but allow Palestinians to actively imagine an alternative reality.

The Israeli NGO Zochrot seeks to raise awareness of the Palestinian Nakba among the broader Israeli public. One of its many projects is iNakba, an interactive smartphone app created in 2014 and downloaded by over 40,000 people to date. iNakba has catalogued over 600 Palestinian towns and villages that were destroyed during the Nakba by providing images, text—in Arabic, Hebrew, and English—and, crucially, Waze and Google Map coordinates to show users how to get there as well as add information themselves.

Creator of iNakba Raneen Jeries said the app is meant to commemorate Palestinian heritage and identity as well as assert the right of return: “We returned the Palestinian village to the map and now we seek to return the Palestinian refugee,” she said. “It’s powerful because it’s interactive…If you’re in the Ein El Hilwa [refugee] camp [in Lebanon], you can be updated about your village in Palestine. It’s brought back to life.”

Zochrot also facilitates projects around the right of return with those affected. For example, the 2010 Participatory Action Research project, Counter Mapping Return, envisioned the spatial possibilities and pitfalls of the Palestinian right of return to one destroyed village, Miska, in the Tulkarem region. Palestinians and Jewish participants created a comprehensive, multi-layered alternative map that dismantled current discriminatory policies. They identified the first step as acknowledgement of the personal and collective destruction caused by the Nakba.

The launch of Palestine Open Maps (a collaboration between Visualizing Palestine and Columbia University Studio-X Amman) in 2018 is the first open-source mapping project based around historical maps from the British Mandate period. The detailed, multi-layered maps narrate visual stories “that bring to life absent and hidden geographies” and allow users to search the pre-Nakba Palestinian landscape. Palestine Open Maps also carries out mapathons allowing users to extract data from Mandate maps (as do other organizations such as US-based NGO Rebuilding Alliance).

Simultaneously, Palestinians are using technology to create their own independent mapping services. Doroob Navigator, for one, which launched in the summer of 2019, crowd-sources road closures and traffic data from its users and allows Palestinian drivers in the OPT to track traffic at checkpoints and design routes they can take.

These projects, among others, including the Gaza War Map, Decolonizing Art and Architecture Residency, and Forensic Architecture, enable Palestinians to oppose and subvert the hegemonic discourse and assert an alternative vision of liberation and return in spatial and cartographic terms. These initiatives are often reinforced by, or juxtaposed with, Palestinian efforts to return to destroyed villages in reality. For instance, the internally displaced inhabitants of villages including Iqrit, Al-Walaja, and Al-Araqib returned decades after their initial expulsion despite the risk of state violence and demolition. More symbolic efforts, such as the Great March of Return in Gaza from 2018 to the present, are another example.

Challenging the Cartographic Gatekeepers

Cartography has long been another weapon in the colonizer’s arsenal: a tool used for the acquisition, control, and erasure of territory. As Israeli political scientist Meron Benvenisti states, “Cartographic knowledge is power: that is why this profession has such close links with the military and war.” In the case of Palestine, British and Zionist cartographic efforts have worked to remove Palestinian traces from the landscape. The decade after 1948 transformed the land, with a fully-formed Hebraicized map taking the place of hundreds of years of Palestinian life and history.

Technology can serve as a tool to tangibly imagine the Palestinian right of return Share on XFor Palestinian refugees, the majority of whom have no recourse to visit, let alone return to the land from which they or their ancestors were ejected, censorship cements their separation from their homeland and restricts it to the virtual sphere. For Palestinians living under martial law in the OPT or under siege in the Gaza Strip, despite technology creating an opening for democratizing spatial practices, mainstream mapping applications fail to account for the walled-off reality on the ground and the restrictions and repercussions it has on Palestinian movement.

However, Palestinians and allies continue to subvert and resist colonial maps through counter-maps. There are some other concrete steps forward:

- As recommended by 7amleh, Palestine should be named properly on Google Maps, in line with the UN General Assembly Resolution of November 2012.

- According to Resolution 181 of the UN General Assembly, the international status of Jerusalem should be correctly displayed on Google Maps. Google must also identify and correctly label illegal Israeli settlements on occupied land, according to Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention and Article 55 of the Hague Regulations.

- Google should clearly distinguish areas A, B, and C in the West Bank and account for all movement restrictions and restricted streets.

- Google should locate “unrecognized” Palestinian villages within Israel as well as Palestinian villages in Area C.

- The United States should dispose of the KBA, leveling the commercial playing field between US and non-US imagery providers. This would allow satellite operators to share high-resolution images of Palestine-Israel on widely-used open-access platforms. It would also enable archaeologists, researchers, and humanitarians to accurately document changes on the ground and allow for better accountability of the Israeli occupation.

- Palestinian civil society should encourage and promote the active use of counter-maps as an alternative to incomplete contemporary maps. Simultaneously, Palestinian civil society and allies should focus their efforts on pressuring (a) the US government to abolish the KBA and (b) Google to make the changes outlined above.

-

To read this piece in Spanish or French, please click here or here. Al-Shabaka is grateful for the efforts by human rights advocates to translate its pieces, but is not responsible for any change in meaning.

- See A Gazetteer of the Place Names Which Appear in the Small-Scale Maps of Palestine and Trans-Jordan, Jerusalem, 1941.