Executive Summary

Since 2021, a growing number of Israeli leaders have proposed new policies to manage their occupation of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and Gaza. These policies are rooted in the new concept of “shrinking the conflict,” an approach introduced by Israeli historian Micah Goodman in 2018 as a solution for reducing the growing rift between the so-called Israeli Left and the Israeli Right over what to do with the regime’s military occupation.

The approach, which is a revised version of Benjamin Netanyahu’s “economic peace” model, assumes that Israeli tools of oppression breed “unnecessary” daily frictions that increase the likelihood of Palestinian “waves of terror and violent clashes.” Therefore, Israel need not dismantle its occupation, but simply manage it differently—ostensibly less oppressively by granting Palestinians more freedom of movement within the West Bank and increasing their economic opportunities with Israel. In this way, the “shrinking the conflict” approach has altogether abandoned any serious discussion of the two-state solution and aims, instead, to entrench the Israeli regime’s military occupation in order to prevent the establishment of either a Palestinian state or a one-state reality.

This policy brief debunks Israel’s “shrinking the conflict” approach and the economic policies it entails. It argues that any proposals that fall short of total dismantlement of Israel’s systems of apartheid, occupation, and settler colonization would bring neither an improvement to Palestinians’ lives, nor their acceptance of the status quo.

The Israeli regime has long employed the economy to control and pacify Palestinians. The “shrinking the conflict” approach is designed to enable a review of the Paris Economic Protocol, including through joint economic collaboration between the Palestinians and Israeli regime. It also proposes additional economic facilities aimed at bringing about Palestinian political acquiescence. For example, Goodman supports gradually devoting additional lands in Area C for Palestinian-Israeli economic cooperation, including foreign investment and industrial parks that would remain under Israeli control.

Moreover, Goodman calls for the creation of “safe” logistic routes within the West Bank to ease the process of transferring Palestinian goods to Israeli markets—the so-called “Door-to-Door” policy—thus incentivizing more Palestinian merchants to strive to enter into economic agreements with the Israeli regime. He also calls for increasing and diversifying Palestinian laborers in 1948 territories, including from Gaza. While they may appear to benefit Palestinians, these two policies entrench Palestinian geographic and economic fragmentation, as well as economic dependence on Israel, in a state of perpetual de-development.

Fundamentally, the concept of “shrinking the conflict” presumes that a series of mainly economic Israeli policy shifts towards the West Bank and Gaza will eliminate the conditions that spur “clashes” between Palestinians and Israeli occupation forces. By supposedly alleviating the severity of Palestinians’ daily suffering, Israel’s military occupation thus becomes more manageable and sustainable. In other words, the question of Palestinian self-determination through statehood becomes obsolete, relieving Israeli leaders across the political spectrum of the perennial question of what to do with the Palestinians.

The approach hinges on a fallacy that Palestinians will be less likely to resist if they are made to believe that they can enjoy life under permanent settler-colonial occupation through fewer restrictions on mobility and more opportunities for economic collaboration with the Israeli regime. It is a distorted and racist assumption based on the long-standing Zionist misconception that Palestinians are an apolitical, violent mob — rather than a people demanding self-determination — that can be pacified if afforded so-called privileges.

Aspects of the “shrinking the conflict” approach have been invalidated with the victory of Netanyahu’s far right-wing coalition government in December 2022. On the one hand, the increased violent Israeli suppression of Palestinian resistance, especially in the northern West Bank, undermined the plan of eliminating the mechanisms that breed clashes. On the other hand, Netanyahu’s extremist coalition, which pushes for further Palestinian dispossession and displacement, is not likely to implement policies for supposedly “shrinking the conflict.” Nonetheless, it is likely that the economic measures put in place since 2021 will continue to shape Palestinian-Israeli economic relations in the coming years.

And while the new Israeli coalition government has yet to lay out its economic policies towards the West Bank and Gaza, its blatant commitment to deepening occupation will certainly worsen Palestinian suffering. Palestinians will never accept this reality, even if Israeli policymakers push for measures aimed at “improving” their lives through increased participation in the Israeli labor market or mobility within the West Bank. So long as Israeli settler colonialism, apartheid, and occupation persist, so, too, will Palestinian resistance.

Overview

Since 2021, a growing number of Israeli leaders have proposed new policies to manage their occupation of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and Gaza. These policies are rooted in the new concept of “shrinking the conflict” — an approach introduced in 2018 by Israeli historian Micah Goodman recommending the management of “the conflict below the threshold of war, while improving the fabric of life for the Palestinian population.” The approach, which is a revised version of Benjamin Netanyahu’s “economic peace” model, aims to entrench the Israeli regime’s military occupation in order to prevent the establishment of either a Palestinian state or a one-state reality. Unlike the “economic peace” strategy, the “shrinking the conflict” approach is designed to reduce Palestinian “waves of terror and violent clashes” by purportedly broadening Palestinians’ freedoms within Israel’s system of apartheid.This policy brief debunks Israel’s “shrinking the conflict” approach and the policy shifts it entails. It examines the government’s new economic decisions vis-a-vis the West Bank and Gaza, outlining their potential serious and irreversible implications for Palestinians. The brief argues that any amendments that fall short of total dismantlement of Israel’s systems of apartheid, occupation, and settler colonization would bring neither an improvement to Palestinians’ lives, nor their acquiescence to the status quo.1

Unpacking the Concept of “Shrinking the Conflict”

Goodman first introduced the concept of “shrinking the conflict” as a solution to the growing rift between the so-called Israeli Left, which has called for an end to the Israeli occupation to prevent a one-state apartheid reality, and the Israeli Right, which opposes any Israeli withdrawal from lands it occupied in 1967. The approach must be understood as a new iteration of the previous “managing the conflict” strategy through “economic peace.” Policies put forth through the “economic peace” strategy entrenched Palestinian economic dependence on the Israeli regime while also implementing oppressive military tactics against Palestinians. By contrast, the “shrinking the conflict” approach assumes that Israeli tools of oppression breed “unnecessary” daily frictions that increase the likelihood of Palestinian grievances, and thus, violent clashes. As part of this strategy, the Israeli regime need not dismantle its occupation, but simply manage it differently – ostensibly less oppressively. In this way, the “shrinking the conflict” approach has altogether abandoned any serious discussion of the two-state solution.The “shrinking the conflict” approach falsely assumes that Palestinian resistance is apolitical and unrelated to the struggle for liberation from Israeli apartheid and occupation Share on XIn other words, “economic peace” policies were introduced to further Palestinian economic dependence on Israel under the guise of two states in order to create a segment of Palestinian society complicit in the continuation of the status quo. Importantly, these policies created a compliant Palestinian economic elite that worked in tandem with Israeli occupation authorities to violently suppress a defiant Palestinian street. Relatedly, the “economic peace” approach did not include provisions for mitigating Palestinian suffering under Israeli military occupation. While the “shrinking the conflict” model continues with similar economic policies, it proposes ways through which the “Palestinian public desire for full civic rights” can be acknowledged without the need for Israel to end its occupation, and without the recognition of Palestinian sovereign borders. Accordingly, affording Palestinians economic facilities, as well as more mobility within the West Bank and access to the outside world, are part of a larger Israeli strategy to limit grievances about the occupation in order to sustain it. This is based on the racist assumption that Palestinians will acquiesce to Israeli settler-colonial occupation if its mechanisms of oppression are eased and made less visible. Fundamentally, the “shrinking the conflict” approach falsely assumes that Palestinian resistance is apolitical and unrelated to the struggle for liberation from Israeli apartheid and occupation. Instead, the framework is based on the belief that most violent confrontations between Palestinians and Israelis stem from the increasingly bitter conditions under which Palestinians live. In this way, the approach assumes that it is not the Israeli occupation per se that perpetuates the conflict, but the way it is managed through overt oppression of the Palestinians. Reconfiguring the occupation to make life “easier” for Palestinians may thus “shrink the conflict” — and a shrunken conflict means the continuation of occupation itself. Despite Goodman’s misguided attempts to bridge the Israeli political spectrum through this approach, the Israeli “Left” is rapidly disappearing and Israeli leadership is now arguably divided between a pragmatic right and an extreme right, both of which reject political negotiations and Palestinian statehood. Thus, any new Israeli measures to “shrink the conflict” — through softening oppressive military tactics or increasing economic opportunities for Palestinians — must be understood as a means of indefinitely extending the status quo of the Israeli regime’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza.

Creating the Illusion of Freedom

In 2019, a group of Israeli students and young politicians established the “Initiative for Shrinking the Conflict” based on Goodman’s eight recommendations for “improving” Palestinians’ lives in a way that also benefits Israel. Since then, the initiative has been part of almost every Knesset session during which the Palestinian economy, Area C of the West Bank, and Gaza are discussed. The “shrinking the conflict” approach also appears explicitly in the New Hope party’s electoral program, and was championed by right-wing Neftali Bennett and so-called centrist Yair Lapid alike. The first four of Goodman’s recommendations are meant to increase a sense of freedom among Palestinians under occupation. First, Goodman advocates for Israeli military plans to connect all Palestinian cantons in Areas A and B with new roads. The proposal is premised on the fact that limited mobility within the West Bank is one of the conditions making Palestinians’ lives particularly difficult, as they are continuously confronted with Israeli checkpoints, settlements, military patrols, and roadblocks. More efficient and linked Palestinian-only roads would help to conceal occupation infrastructure, theoretically giving Palestinians the sense that the occupation has somehow disappeared.Goodman also suggests transferring parts of Area C to Area A in order to better enable Palestinians to expand their housing according to need. However, this does not imply a gradual Israeli withdrawal from Area C; rather, it implies that Israel is willing to transfer limited portions of Area C to the Palestinians because they are adjacent to Palestinian villages and are unsuitable for settlement expansion. Moreover, Palestinians are quick to point out that these gestures are often linked to Israeli settlement expansion. In 2021, and for the first time in 20 years, the Israeli regime approved the construction of more than 1,000 housing units for Palestinians in Area C only days after it approved the construction of 2,200 Israeli settlement units, also in Area C. In this way, any transferral of parts of Area C to Area A for Palestinian housing development that is accompanied by Israeli settlement expansion would further Palestinian resistance.2The “shrinking the conflict” strategy also necessitates easing Palestinian connectivity to the outside world. To this end, Goodman proposes granting Palestinian access to Israeli airports. In 2022, the Israeli regime took a step toward this, permitting Palestinians from the West Bank to use Ramon airport, located in the southern Naqab, for travel. While seemingly beneficial on the surface, this step only exacerbates Israeli control over Palestinians. Indeed, to access Ramon airport, Palestinians need to rely on Israeli transportation infrastructure, which compels the Israeli regime to increase its surveillance mechanisms. Finally, Goodman paradoxically recommends that Israel support Palestinian diplomatic efforts to gain international recognition as a state, but not recognize the borders of a Palestinian state. While recognition of statehood would “increase the Palestinians’ sense of freedom and independence,” Goodman explains, without recognizing Palestinian borders, Israeli occupation forces’ incursions into the West Bank will continue to not be considered violations of sovereign territory — an important component of his original proposal in Hebrew that was omitted from the English translation. Regardless, support for Palestinian statehood is unlikely to occur under any Israeli regime, especially under Israel’s new extreme-right coalition government.

The Economic Components of “Shrinking the Conflict”

The Israeli regime has long employed the economy to control and pacify Palestinians. This is laid out in the 1994 Paris Economic Protocol (PEP), an agreement between Israel and the Palestinian Authority (PA) intended to give the illusion of Palestinian economic autonomy while paradoxically rendering Palestinians economically dependent on the Israeli regime. Over the course of the past five years, Israeli leadership has done little more than evolve Netanyahu’s “economic peace” model, which falls squarely within the PEP framework. Israel is insidiously ensuring the de-facto annexation of important hubs of Palestinian economic production, as well as silencing Palestinian dissent through offering them economic incentives Share on XCrucially, any new Israeli economic policies that offer Palestinian merchants and laborers opportunities for mobility and collaboration with Israel in order to supposedly raise their standard of living — and thus, “minimize” the conflict — are fundamentally erroneous and illogical. They must be understood as a way of entrenching Palestinian geographic and economic fragmentation, as well as economic dependence on Israel, in a state of perpetual de-development.

Goodman’s Take on Economic Relations

Goodman’s “shrinking the conflict” approach is designed to enable a review of the PEP, including through joint economic collaboration between the Palestinians and Israeli regime. As part of this approach, former Israeli Prime Minister Yair Lapid and Palestinian Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh attended a meeting in September 2022 sponsored by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the goal of which was to promote Palestinian state-building. The Ad Hoc Liaison Committee subsequently proposed to restructure financial relations between the Palestinians and Israelis, as well as the revival of the Joint Economic Committee, which was frozen after the Second Intifada. To date, neither of these proposals has advanced, and both will likely be altogether abandoned under Netanyahu’s sixth government. Goodman also proposes additional economic facilities — based on policy shifts recommended by the Institute for National Security Studies — aimed at bringing about Palestinian political acquiescence. For example, he supports gradually devoting additional lands in Area C for Palestinian-Israeli economic cooperation, including foreign investment and additional industrial parks that would remain under Israeli control. These would join existing projects, such as the Bethlehem Multidisciplinary Industrial Park (BMIP) and the Jericho Agro Industrial Park Company (JAIP Co.), neither of which have succeeded in their goals of supporting Palestinian economic growth. To be sure, Goodman’s proposal hinges on foreign investment — an important reminder that “shrinking the conflict” also serves the interests of stakeholders beyond colonized Palestine.Moreover, Goodman calls for the creation of “safe” logistic routes within the West Bank to ease the process of transferring Palestinian goods to Israeli markets, thus incentivizing more Palestinian merchants to strive to enter into the arrangement with the Israeli regime. He also calls for increasing and diversifying Palestinian laborers in 1948 territories. While they may appear to benefit Palestinians, these two policies only further their economic subjugation:

The Creation of “Safe” Logistic Routes

Since 2018, the Israeli Civil Administration, USAID, and the Quartet, alongside several Palestinian large-scale producers, have worked on a new model to export Palestinian goods to Israeli markets by enabling Israeli trucks to enter Area A and load goods directly from the doors of Palestinian factories. The new model, known as the “Door-to-Door” arrangement, significantly reduces time spent transferring products and streamlines the process of getting Palestinian merchandise into Israeli markets.The arrangement is promoted as financially beneficial to Palestinian large-scale producers who would be able to raise production and increase their profits after complying with Israeli conditions. However, it includes several requirements for Palestinians that revolve around security: 1) Palestinian factories must erect cement barriers and wire fences, supported by an alarm system connected directly to an Israeli military office at the nearest commercial gate; 2) Palestinian employees, trained by the Israeli military, must load the Palestinian cargo and report daily to their Israeli military supervisors; and 3) every freight truck must install a GPS tracking system that allows Israeli military agents to surveil shipments on the road through the West Bank. As of September 2022, 21 Palestinian companies in al-Khalil (Hebron), Ramallah, and Nablus have entered into the door-to-door arrangement.3 The total shipments using this method amounted to 61,880 between March 2018 and September 2022, reducing logistical costs by approximately $8.6 million. As with the “economic peace” model, this arrangement ensures that a portion of large-scale Palestinian producers are separated from the remainder of Palestinian exporters, who suffer as a result. Indeed, Israeli occupation authorities require that Palestinians entering into the door-to-door arrangement must exceed the volume of their trade with Israel by NIS 10 million annually — an output to which very few Palestinians can aspire. Beyond worsening the Palestinian wage gap across a fragmented geography, the door-to-door policy enables further Israeli encroachment upon Palestinian land and surveillance over their daily lives. The arrangement entails that the Israeli regime infiltrates Palestinian production sites in Area A, where factories are located, whenever it deems necessary. Israel also surveils these production sites, as well as the “safe” logistic routes reserved for the door-to-door freights, thereby significantly expanding its oppressive surveillance infrastructure over Palestinians. Israeli occupation forces have likewise intensified security background checks as part of their permit regime, ensuring that an increasing number of Palestinians are politically pacified in order to preserve their work permits and economic livelihoods. Altogether, such policies indicate that Israel is insidiously ensuring the de-facto annexation of important hubs of Palestinian economic production, as well as silencing Palestinian dissent through offering them economic incentives.

Deepening Economic Dependence through Labor

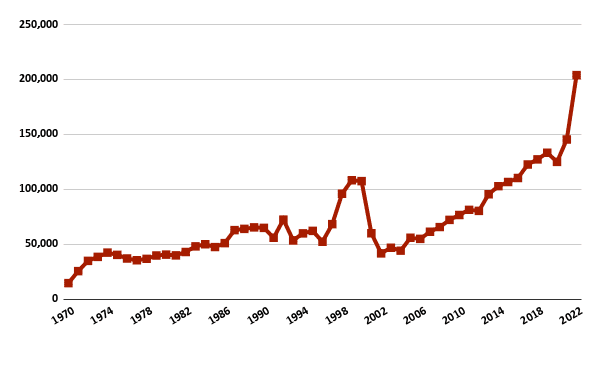

In late 2016, the Israeli regime issued a resolution calling for major “innovations” regarding both the volume of permitted Palestinian workers in 1948 territories, as well as the procedures for issuing worker permits. Since then, the government has legislated several resolutions to implement these “innovations.” As a result, the number of Palestinian workers in 1948 territories has increased from about 110,000 in 2016 to 204,000 in 2022. This shift aligns with Goodman’s fifth step toward “shrinking the conflict:” increasing the number of Palestinian workers in the Israeli labor market (with a cap of 400,000).

Figure 1: The number of Palestinian workers migrating to Israeli workplaces between 1967-2022. Source: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS).4

Likewise, in March 2022, Israel issued Decision 1328 to allow Palestinian workers from Gaza to enter 1948 territories for the first time since 2006. By the end of 2022, the number of permitted workers from Gaza was capped at 20,000. Understood within the context of “shrinking the conflict,” the Israeli regime’s approach towards Gaza in particular has shifted from “calmness for calmness” to “economy for calmness,” as Yair Lapid, then foreign minister, explicitly stated in September 2021. Importantly, apart from affording Palestinians from Gaza economic opportunities in 1948 territories, Gaza itself is altogether excluded from Goodman’s proposal.

While Israeli authorities argue that the increased income flow into the West Bank and Gaza will contribute to Palestinian economic growth — in 2021, it was estimated that the combined income of Palestinian workers in 1948 territories reached $5.5 billion (about 35% of Palestinian GDP) — a distinction must be made between such growth and economic development, especially under restrictive military occupation and siege. Instead, increasing Palestinian labor migration to the Israeli market fundamentally entrenches Palestinian dependence on Israel and, therefore, the Israeli occupation.

Even if Israeli policymakers push for measures aimed at “improving” Palestinians’ lives…the reality of Israeli settler colonialism, apartheid, and occupation will persist — as will Palestinian resistance to it Share on X

To make matters worse, the Israeli regime is no longer only interested in low-wage Palestinian labor. In recent years, it has diversified the Palestinian labor force in 1948 territories to include those in the fields of high technology, medicine, and engineering. It has also invested about NIS 300 million to train Palestinian workers in new professional skills. In this way, the expansion and diversification of Palestinian laborers does nothing more than increase the number of Palestinians who are economically dependent on the Israeli regime and the preservation of the political status quo.

Why “Shrinking the Conflict” will Fail

The concept of “shrinking the conflict” presumes that a series of Israeli policy shifts towards the West Bank and Gaza — namely economic — will eliminate the conditions that spur “clashes” between Palestinians and Israeli occupation forces. By supposedly alleviating the severity of Palestinians’ daily suffering, Israel’s military occupation thus becomes more manageable and sustainable. In other words, the question of Palestinian self-determination through statehood becomes obsolete, relieving Israeli leaders across the political spectrum of the perennial question of what to do with the Palestinian population. Ultimately, the “shrinking the conflict” framework reveals that the Israeli regime will continue to operate to its own benefit at the expense of the Palestinians, including sustaining the very structures of settler-colonial apartheid that are foundational to their ongoing suffering. Indeed, as Goodman himself argues, “shrinking the conflict” does not necessitate a formal agreement, the withdrawal of Israeli settlers or settlements from the West Bank, or the division of Jerusalem. In this way, Goodman’s eight steps hinge on a fallacy: Palestinians will be less likely to resist if they are made to believe that they can enjoy life under permanent settler-colonial occupation through fewer restrictions on mobility and more opportunities for economic collaboration with the Israeli regime. It is a distorted and racist assumption based on the long-standing Zionist misconception that Palestinians are an apolitical, violent mob — rather than a people demanding self-determination — that can be pacified if afforded so-called privileges. Aspects of the “shrinking the conflict” approach favored by the Israeli pragmatic right have been invalidated with the victory of Netanyahu’s far right-wing coalition government in December 2022. On the one hand, the increased violent Israeli suppression of Palestinian resistance, especially in the northern West Bank, undermined the plan of eliminating the mechanisms that breed clashes. On the other hand, Netanyahu’s extremist coalition, which pushes for further Palestinian dispossession and displacement, is not likely to follow Bennett and Lapid’s proposals for supposedly “shrinking the conflict.” Nonetheless, it is likely that the economic measures put in place since 2021 will continue to shape Palestinian-Israeli economic relations in the coming years. And while the new Israeli coalition government has yet to lay out its economic policies towards the West Bank and Gaza, its blatant commitment to deepening occupation will certainly worsen Palestinian suffering. Palestinians will never accept this reality, even with increased economic facilities. That is to say, even if Israeli policymakers push for measures aimed at “improving” Palestinians’ lives through increased participation in the Israeli labor market, mobility within the West Bank, or access to the outside world, the reality of Israeli settler colonialism, apartheid, and occupation will persist — as will Palestinian resistance to it.

- All translations of Arabic and Hebrew sources in this policy brief were completed by the author.

- It is highly unlikely that proposals for expanding Palestinian housing will continue under the new Israeli regime.

- Importantly, some Palestinian capitalists elected to enter into the door-to-door arrangement.

- The PCBS website only offers data since 1994. To access data between 1967 and 1993, the author consulted PCBS annual reports as well as Leila Farsakh’s book, Palestinian Labour Migration to Israel: Labour, Land and Occupation (Oxford: Routledge, 2005).