Executive Summary

- Palestinian farmers have always been on the frontlines of resistance and continue to defy settler encroachment.

- Oslo and its accompanying treaties slowly dismantled the popular structures created through anti-colonial organizing with the new pretext of “state-building.”

- The failure of the PA to challenge decades of de-development induced by the Israeli regime has left the Palestinian economy heavily segmented, characterized by high levels of unemployment.

- The mainstream approach to food security has traditionally focused on providing access to food through trade or food aid. This model tends to ignore the power dynamics that mediate food access.

- The notion of food sovereignty arose from a need to rethink the food security paradigm and address its shortcomings in the Global South.

- Food sovereignty is understood as “the right of Peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.”

- Food sovereignty can provide an alternative source of livelihood, which means more space for resistance and to act without fear of hunger.

- A successful shift to food sovereignty cannot be separated from a broader socio-political movement encouraging Palestinians to support their farmers, even when the price is relatively higher.

- The Palestinian community should take concrete steps to recenter food sovereignty—including creating a food sovereignty fund, developing trade and solidarity networks with Palestinian farmers, broadening boycotts of Israeli goods, investing in agrotechnology, and strengthening popular education on agroecology.

Introduction

In their struggle against Zionist settler colonialism, Palestinians have long worked towards establishing a resistance economy. Understood as a form of popular organizing such that economic institutions and activities serve the political aims of the Palestinian struggle, the notion of a resistance economy emerged organically during the early decades of the liberation struggle and later became a central pillar of the First Intifada. During this time, economic autonomy was regarded as a means to sustain the anti-colonial struggle.1

Today, food sovereignty constitutes a natural continuation of such modes of resistance, building upon the principles of agricultural self-sufficiency practiced throughout the history of the Palestinian revolution. Accordingly, this policy brief traces the origins of food sovereignty and the challenges Palestinians face to effectively put the framework into practice. The brief argues that doing so will help better recontextualize the resistance economy today, thus paving the way for establishing a more contentious economic order.

Agriculture and the Resistance Economy: Past and Present

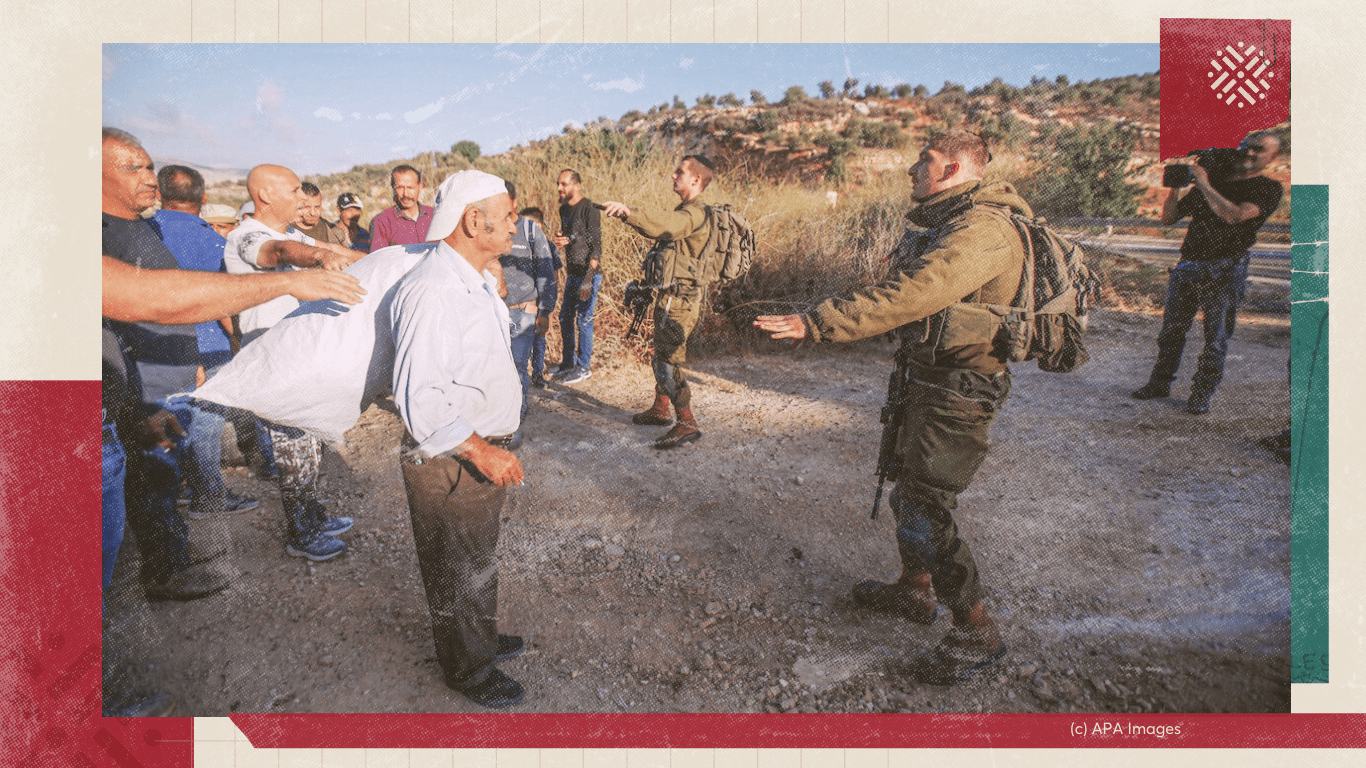

For Indigenous people resisting settler colonialism, control over land often means control over life. Palestinian farmers have always been on the frontlines of resistance and continue to defy settler encroachment.

Agriculture—specifically, agricultural cooperatives—was historically a core component of the Palestinian resistance economy. This mode of production faced a tremendous setback during the Nakba, with the loss of most Palestinian lands and the ethnic cleansing of nearly one million Palestinians. Consequently, agricultural cooperatives dropped by 87% within a few years of the Nakba. While they have never fully recovered, Palestinian farmers have made notable efforts to sustain agriculture as a key component of economic resistance.

Agriculture—specifically, agricultural cooperatives—was historically a core component of the Palestinian resistance economy Share on X

One such example is the “victory gardens” of the First Intifada. These gardens were grassroots initiatives focused on small-scale agriculture at the household and neighborhood levels. Cooperatives, such as “The Shed,” also emerged during this period. Based in Beit Sahour, the Shed provided seeds, tools, and insecticide at cost to Palestinians in the surrounding areas. As a result of these and similar projects, it is estimated that over 500,000 trees were planted across Palestine between 1987 and 1989. At the time, Yitzhak Rabin was so infuriated by these efforts that he instructed the army to impose curfews on Palestinian villages during harvest times so that their crops would rot in the field.

While agriculture’s economic role was crucial to the Palestinian resistance economy, its political and social dimensions should not be overlooked. These projects carried with them a rejection of the colonial condition. The communal emphasis on household and neighborhood production helped nurture collective and popular participation and solidarity. Despite some challenges and setbacks, this production and consumption model successfully drew engagement from wide segments of society.

Settler Colonialism and De-Development

Colonial authorities also understood the link between economics and politics. From its inception, the Zionist settler enterprise sought to expropriate Palestinian land and resources and render Palestinians dependent on the Israeli economy. General Moshe Dayan once commented that controlling infrastructure and utilities is more effective than “a thousand curfews and riot-dispersals.”

One way that Israel has sought to achieve this dependency is through the process of de-development. Prior to the signing of the Oslo Agreement, the Israeli regime pursued de-development through the fragmentation and isolation of Palestinian population centers and the expropriation of their lands and resources. After Oslo, these policies continued with an added layer: the Protocol on Economic Relations (Paris Protocol), which institutionalized de-development under the guise of “transitional negotiated agreements.” The protocol included the devastating, one-sided customs union, as well as bodies such as the “Joint Water Committee,” which continues to divert fresh water to illegal settlers and hold Palestinians hostage to a system of racist military permits to this day. The Paris Protocol was a formalization of the same colonial systems of expropriation that existed prior but now came coated with a sheen of legitimacy, rubber-stamped by the supposed representatives of the Palestinian people. It was the selling of domination as cooperation.

Oslo and its accompanying treaties slowly dismantled the popular structures created through anti-colonial organizing with the new pretext of “state-building.” Today, the Palestinian Authority (PA) dedicates less than 1% of its budget to agriculture. Economic development has long since been decoupled from any emancipatory political program and now serves as a litmus test to prove to the international community that Palestinians are “ready” for statehood.

The failure of the PA to challenge decades of de-development induced by the Israeli regime has left the Palestinian economy heavily segmented, characterized by high levels of unemployment, especially among the youth, with levels reaching as high as 48%. The stagnant job market, the Israeli settler-colonial restrictions, and the atomization of Palestinian urban centers have made working in Israeli settlements and in the 1948 lands one of the only remaining options for Palestinians to feed their families. As much as 10% of the Palestinian workforce in the West Bank depends on labor in illegal colonies and in the colonial economy more broadly.

All imports and exports are dependent on the Israeli regime’s whims, while movement restrictions cost the Palestinian economy an estimated $274 million and 60 million working hours annually. Vast fertile lands are cordoned off for settlement expansion; most Palestinian farmers struggle to reach their lands and do not have the resources to develop them. Combined with the PA’s neglect of this sector, these factors have contributed to agriculture’s gradual erosion and abandonment, which has declined from 53% of GDP in 1967 to less than 7% in 2021.

The majority of those who still practice farming today do so as a secondary activity. Barely 26% of Palestinian farmers report farming as their main income-generating activity. Farming land has gradually shrunk and become more fragmented. Between 2004 and 2010, the average agricultural landholding dropped from 18.6 dunums to 10.8—a 42% decrease over just six years. Three-quarters of agricultural holdings in Palestine are less than 10 dunums; however, they make up only 20% of farming land. Hence, extreme contrast defines agriculture in Palestine—a sector caught between the smallholder majority, growing for subsistence, and the for-profit minority that controls most of the land.

Food Security Under De-Development

Globally, the mainstream approach to achieving food security is based on the 1996 Rome declaration and has traditionally focused on providing access to food, mostly through trade or food aid. This model, however, tends to ignore the power dynamics that mediate food access. Critically, reliance on trade makes Palestinians vulnerable to exogenous shocks. The initial years of the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted this risk, when the disruption of international trade and food imports exacerbated food insecurity. The economy’s shutdown caused many to lose their income and, consequently, the ability to afford food. Food security also brings with it the risk of dependency on the whims of the international community and its stipulations.

In a context where Israeli settler colonialism polices every action, the mainstream food security paradigm is simply inadequate Share on X

In a context where Israeli settler colonialism polices every action, the mainstream food security paradigm is simply inadequate. For instance, donor states championed the Amoro mushroom farm in the West Bank as an example of innovative entrepreneurial thinking to alleviate Palestinian economic woes. But while the farm sought to break the monopoly of Israeli mushrooms in the Palestinian market, the Israeli response was swift. Indeed, Israeli forces threatened grocers who switched to the Palestinian product and purposefully delayed the delivery of the imported spores needed to grow the mushrooms at its port until they expired. This suppression effectively shut down the farm’s production, ending the project.

In Gaza, the Israeli regime has historically dictated everything that may enter the besieged strip. Using herbicidal warfare, Israel likewise determines how much food Palestinians in Gaza are allowed to produce by making large swaths of agricultural land unusable. Even more dire, the genocide unfolding since October 7th, 2023, shows that the Israeli regime has been actively using thirst and mass starvation as a weapon of war against Palestinians. These actions can only be understood as an attack on the infrastructure of Palestinian life itself.

Meanwhile, in the West Bank, whatever illusion of economic stability offered in return for obedience has been dispelled since October 2023, with the closure and isolation of cities and revocation of work permits within 1948 Palestine, as well as withholding PA tax returns. These measures underscore the West Bank economy’s vulnerability and severe dependency on Israeli approval.

Food Sovereignty and Palestine

The notion of food sovereignty arose from a need to rethink the food security paradigm and address its shortcomings in the Global South, especially in the context of World Bank and IMF-imposed structural adjustment programs that encouraged the commodification of food. Tracing its origins to agrarian peasant movements in Latin America, food sovereignty is understood as “the right of Peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.”

A leading voice in the food sovereignty movement is La Via Campesina (The International Peasant Movement), a global coalition including hundreds of peasant groups worldwide that oppose the top-down organization of food production systems and work to reclaim land and resources from the exploitation of capital. La Via Campesina promotes agroecology principles and stresses preserving local ecosystems in lieu of destructive industrial farming practices. Although each country in the peasant movement has its context-specific struggles, they are all threatened by the exploitation of land, labor, and resources. In this context, members from all over the world exchange knowledge and experiences towards achieving food sovereignty.

Importantly, food sovereignty as a concept is broader than food security. It centers on small-scale farmers and seeks to build sustainable local food production. In contrast to the food security paradigm, this approach focuses on reclaiming land and resources, creating communally organized production, and building the infrastructure needed to support a resistance economy. This perspective starkly contrasts with the cash-crop export orientation strategy currently employed, in which impoverished and hungry Palestinians are encouraged to grow flowers to export to European markets instead of achieving a basic level of self-sufficiency.

Palestinian farmers have embraced the movement: Palestine is notably the first Arab member of La Via Campesina. This membership was the culmination of decades of work by the Union of Agricultural Work Committees and the Palestinian Agricultural Relief Committees, among other organizations. Their activities and support for agricultural committees in hundreds of villages during the First Intifada helped to solidify resilience among farmers and emphasized the importance of agricultural independence and self-sufficiency.

Towards Food Sovereignty Today

The struggle for food sovereignty in Palestine is a major battlefield against Zionist settler colonialism, as it contains within it multiple facets of social, economic, and political resistance. A Palestinian return to tending land, organized through participatory and collaborative democratic principles, would reduce food insecurity and increase society’s capacity for resistance. It would reaffirm the role of farmers as stewards of the soil and resistance, and the continuous utilization of land would make their confiscation or theft by settlers more difficult.

An additional benefit is that it would make Palestinian communities more resistant to closures. Focusing on local inputs, flora, and fauna means that the endeavors would be more sustainable, enabling them to also blunt the destabilizing impacts of global shocks.

The struggle for food sovereignty in Palestine is a major battlefield against Zionist settler colonialism, as it contains within it multiple facets of social, economic, and political resistance Share on X

As it stands, Israel and its accomplices have engineered Palestinian livelihood to be heavily dependent on Israeli control and approval. This has the effect of domesticating Palestinians and discouraging any form of resistance through deploying various schemes. For instance, the overwhelming majority of Palestinians in the West Bank now live either in cities or refugee camps, with only 22% remaining in rural areas. These same rural areas provide the largest source of exploitable Palestinian labor within the colonial economy. Necessarily, the move to food sovereignty must contend with the enforced proletarianization of Palestinian farmers. Any advancements will require disentangling Palestinian workers from the grip of Israeli capital— and, consequently, complicit Palestinian capital.

Food sovereignty can provide an alternative source of livelihood, which means more space for resistance and to act without fear of hunger. But this raises uncomfortable questions that Palestinians must be able to answer: Who will cover these costs and bear the burdens of this approach? How will the rest come together to support those who cultivate the land? What sacrifices are Palestinians willing to make to ensure the success of a resistance economy? After all, many abandon their lands and flock to work in the colonial economy because agricultural production, on average, cannot provide a similar income level. This is exacerbated by the dominance of Israeli fruit and vegetables in the Palestinian market, as Israeli control over land, water, resources, and transportation means that Palestinian farmers cannot hope to compete against Israeli products on a pure price-to-price basis.

Thus, a successful shift to food sovereignty cannot be separated from a broader socio-political movement encouraging Palestinians to support their farmers, even when the price is relatively higher. Locally produced food should not be seen as mere sustenance but also as an investment in a more contentious economic order and a step toward a more dignified future. This approach is especially key for strategic crops, such as wheat, which are often cheaper to procure from abroad. Those who can return to the land should be encouraged to do so; those who can’t have a duty to support them and help share their burden, be that through subsidies or collaboration.

Therefore, if food sovereignty is to be the base of a resistance economy, more substantive change beyond consumption habits is required. It necessitates regenerating our relationship with the land and transforming our methods of production and consumption.

Food Sovereignty Under Genocide?

Until October 2023, Gaza was heavily dominated by urban sprawl, with few accessible rural areas available for agriculture. Gaza’s ability to produce 44% of its food in a mostly urban setting was remarkable, as urban environments rarely meet their food or water needs without a large rural countryside, even under normal circumstances. Without the ingenuity of Palestinians in Gaza, such as extracting gas and fertilizer from waste streams and utilizing their rooftops for growing crops, food insecurity within the territory would have been much worse.

Nonetheless, the limits of advocating for a food sovereignty approach while genocide and open warfare continue must be acknowledged. For instance, regenerative agricultural practices that aim to rehabilitate soils and create increased fertility are not able to take root, as Israeli forces routinely bombard the precious few agricultural zones in Gaza. By June 2024, the Israeli genocide had already destroyed 75% of agricultural zones in Gaza. While the destruction of trees and orchards also occurs in the West Bank, the scale of the genocide in Gaza and the wanton destruction has reached unparalleled levels.

Hence, food sovereignty cannot be viewed as a cure-all to counteract every facet of settler colonialism. Rather, its role is to spur the conditions to make resistance and confrontation possible and mitigate the subsequent damage.

Conclusion

Political opportunities can arise when least expected, and challenges to the status quo can ignite widespread change. Palestinians must accordingly lay the groundwork to better support the rise of a resistance economy. We must do so not in mere anticipation of political opportunity, but with the mindset of actively creating these conditions in the present. This need not mean formulating a comprehensive blueprint for a resistance economy; after all, it was only after the First Intifada that the victory gardens emerged. Systemic change at this level will result from a thousand small battles preceding, during, and after the inevitable outbreak of the next Intifada.

Now more than ever, it is critical to our survival as a people to build dual power and food sovereignty to bolster our steadfastness and resistance. History has shown that this change will not come from above and that such endeavors are at odds with the PA’s strategy. Palestinians cannot expect any protection or support from their officials, especially in the face of unprecedented settler aggression. Therefore, we must plan accordingly and collectively on communal and grassroots levels to create the conditions necessary for resistance.

Recommendations

The Palestinian community, including those across colonized Palestine and those in the diaspora, should coordinate to implement the following actions to recenter food sovereignty within a resistance economy:

- Create a food sovereignty fund—potentially financed by the Palestinian diaspora—to reduce reliance on foreign aid and help establish agricultural resistance initiatives and projects.

-

- This would have the added benefit of steering development away from a purely entrepreneurial approach, as is often a feature of foreign development aid. The fund would need to be democratically controlled, with the highest levels of transparency. The Palestinian Social Fund could serve as a basic model to build upon.

- Support the development of Palestinian trade and solidarity networks connecting Palestinians wherever they are with farmers.

- The purchase of goods at a premium price, especially by Palestinians in the diaspora and within the green line, could help facilitate the transfer of wealth to local farmers. Such networks may also help subsidize less profitable yet important strategic crops, such as wheat.

- Broaden socially-backed boycotts of Israeli goods, stigmatize consumption of Israeli products, and prioritize purchasing Palestinian products.

- Invest in agrotechnology to maximize the efficiency of available resources.

-

- While expanding the land utilized for agriculture is important, studies show that well-maintained and irrigated smallholdings can be up to 28 times more productive (per dunum) than purely rainfed holdings. Given the theft of Palestinian water sources by Zionist settler colonialism, focusing on maximizing the efficiency of the meager available resources could have a more productive effect overall. Simple technologies—such as wicking beds— provide a water-efficient irrigation method and reduce the amount of farming labor. High-density trellising can be used to double or even triple the yields of fruit tree production compared to traditional orchards, in addition to reducing labor, water, land, and fertilizer needs. Such measures require higher establishment costs and special training for farmers, but would be much more resilient and productive in the medium to long-term.

- Utilize waste streams that are typically discarded, such as manures and organic and market waste, to produce fertilizers, biogas, or components for animal feed.

- Internalize the lessons of peasant movements in the Global South and embrace Indigenous fauna and flora in agricultural endeavors.

-

- For example, animal husbandry in Palestine can be prohibitively costly in terms of water and feed, and the main dairy companies focus exclusively on cow milk. A shift to browsers (camels and goats) instead of cattle could reduce water consumption by up to 50% and feed consumption by up to 35% per liter of milk produced. An additional benefit would be that browsers are more flexible with their feed composition and more resilient than cows if faced with drought or hunger. Furthermore, they produce less manure, reducing their environmental footprint and the chance of tainting groundwater sources.

- Educate local populations on agroecology to dispel the notion that it is an imported idea with no practical benefits beyond procuring foreign funding. Work to shift Palestinian mindsets to align with traditional farming principles, promoting a return to the agriculture of our grandparents, who did not rely on imports or environmental destruction.

-

- One ancient Palestinian farming technique that could be revived is using mist to water plants with mist catchers in areas with suitable humidity levels.

- Calculate the feasibility of any project involving strategic resources or staple crops, emphasizing strategic or political utility over pure economic performance.

-

- For example, growing our own wheat might be more costly under the current circumstances, but uninterrupted and locally controlled access to its production is crucial for resilience.

- Encourage the establishment of stockpiles of strategic goods that are easy to access in case of emergency or blockade.

- Encourage the establishment of a comprehensive network of complementary cooperatives to produce, process, and sell food.

-

- Once established, agricultural cooperatives should become active parts of their respective communities and perform a positive social function to attract more Palestinians to this model. They could form a core model to challenge neoliberal economic policy and its focus on individualistic notions of success.

- To read this piece in French, please click here. Al-Shabaka is grateful for the efforts by human rights advocates to translate its pieces, but is not responsible for any change in meaning.

Fathi Nimer is Al-Shabaka’s Palestine policy fellow. He previously worked as a research associate with the Arab World for Research and Development, a teaching fellow at Birzeit University, and a program officer with the Ramallah Center for Human Rights Studies. Fathi holds a master’s degree in political science from Heidelberg University and is the co-founder of DecolonizePalestine.com, a knowledge repository for the Palestinian question. Fathi’s research revolves around political economy and contentious politics. His current focus is on food sovereignty, agroecology, and the resistance economy in Palestine.