Executive Summary

The Israeli occupation has distorted Palestine’s economic structure by crippling its productive sectors, including agriculture, construction, and manufacturing, leaving them unable to contribute to Palestinian GDP and employment. This has led to the dominance of internal trade in the Palestinian economy, which is the retail and wholesale buying and selling of goods, including with Israel. The dominance of internal trade in the Palestinian economy is a direct result of Israel’s military occupation, which has led to Palestine’s economic dependence on Israel since 1967.

This brief examines internal trade as a microcosm of the Palestinian economy as a whole, highlighting the futility of international and donor support for development under occupation. It calls on international financial institutions and the international community to support Palestinian economic self-determination by empowering independent, transparent, accountable, and collective Palestinian policy-making outside of the Palestinian Authority’s failed leadership.

Data from PCBS National Accounts show that internal trade has played an increasingly key role in contributing to total Palestinian value-added (i.e. GDP). In 2018, internal trade accounted for 22% of the total Palestinian GDP ($3.6 billion in 2018). This reality reflects the ongoing dependency relationship of the Palestinian economy on Israel, a relationship which has been exacerbated since the 2nd Intifada (2000-2005) after which almost all Palestinian economic sectors were curtailed.

In addition, since the private credit boom in 2008, internal trade has been the largest economic sector granted credit facilities and loans, comprising between 20-25% of total private sector credit. The amount of credit supplied for internal trade activities increased from roughly $300 million in 2008 to $1,350 million in 2019, a near 350% increase in ten years. This indicates a serious blow to Palestinian productive sectors. Understanding how this reality came to be requires an examination of Palestinian economic history that relays the structural distortions created by the Israeli occupation, and the dependency relationship resulting from Israeli colonial economic policies implemented since it occupied Palestine in 1967.

Over the course of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem, natural resources (such as land, water, and minerals), unfinished goods, and human resources (labor) moved from the periphery-Palestinian to the center-Israeli economy, while final goods moved from the Israeli to the Palestinian economy. This reflects the entrenched dependency of the Palestinian economy on Israel which did not change after the establishment of the PA in 1994. On the contrary, fueled by international aid and the availability of credit following the 2nd Intifada, the trade deficit reached a peak of $5.5 billion in 2019, with more than half (55%) of that deficit attributed to trade with Israel. On average, since the establishment of the PA, Palestinian trade has been dependent on Israel for 75% of its imports and 80% of its exports.

These trends evince another reality: trade in Israeli goods has slowly become the main economic activity in the West Bank and Gaza, a reality which was deliberately designed by the Israeli regime. Indeed, some of the first military orders issued by Israel were economic in nature, the result of which was to shut down all banks operating in the West Bank and Gaza, and to impose a complex web of administrative procedures and permit restrictions that remain in place to this today. These restrictions have made it virtually impossible for Palestinians to start a business or import new machinery, including for construction. Yet this has not stopped owners of large economic establishments and heads of chambers of commerce in Palestinian cities to reap fortunes from the occupation.

The dominance of internal trade in the Palestinian economy has led to a shift away from production activity, and toward activities that provide less room for economic development and transformation. However, this trend is not irreversible. International financial institutions, including the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, as well as the international community and aid agencies in general, must do the following in order to support Palestinian economic self-determination:

- Recognize that the relationship between the Palestinian and Israeli economies has destroyed any viable development for the Palestinian economy.

- Provide direct international aid to support Palestinian farmers in areas that are facing the threat of annexation.

- Pressure the Israeli regime to facilitate licenses in Area C, including building permits for residential and business structures.

- Empower independent Palestinian policy-making by supporting independent research centers and scholars, labor unions, and representatives of groups normally absent from decision-making, including women, youth, and refugees.

- Exert pressure on the Israeli government to end its occupation in order for Palestinians to have control over their own economic policy.

- Recognize that ending the Israeli occupation will also lead to the Palestinian private sector flourishing and thriving.

Overview

The Israeli occupation has consistently inflicted disastrous economic costs on the Palestinians, costs that economists have examined for decades. One dimension that has been missing in these examinations, however, relates to the distortions in the structure of the Palestinian economy, and the detrimental impacts of these distortions. The term economic structure refers to the contribution of different economic sectors, including agriculture, manufacturing, construction, and trade, to the key macroeconomic variables of output (GDP) and employment. Whereas a comprehensive study of these structural distortions is beyond the scope of this brief, we zoom in on one particular economic sector that has been playing an increasingly dominant role in the Palestinian economy: internal trade. Briefly, internal trade refers to the retail and wholesale buying and selling of goods, including trade with Israel. The increased relevance of the contribution of internal trade to total economic activity in Palestine is part of an ongoing shift away from productive sectors, such as agriculture and manufacturing, towards services, trade, and construction.This brief argues that the dominance of internal trade at the expense of productive sectors is neither a result of a conscious policy effort by the Palestinian Authority (PA) nor an outcome of “laissez faire” market governance. Rather, it is a byproduct of Israeli occupation policies, and a clear consequence of the Palestinian economy’s dependence on the Israeli economy since 1967. The brief argues that internal trade is a microcosm of the Palestinian economy as a whole, highlighting the futility of international and donor support for development under occupation. Rather, what is needed involves empowering independent, transparent, accountable, and collective Palestinian policy-making, a quality of leadership and governance that the Palestinian leadership of the last 25 years cannot lead or carry out.

The Dominance of Internal Trade in Palestine

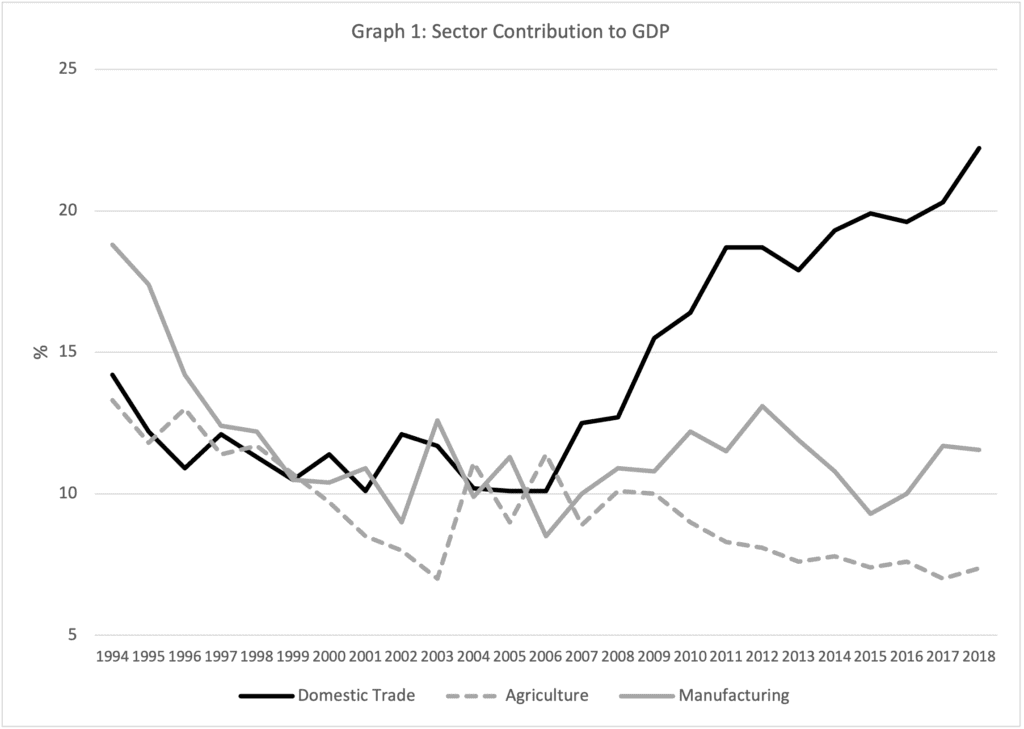

Before delving into the data that demonstrates the current dominance of internal trade in the Palestinian economy, it is useful to familiarize ourselves with the economic activities and subsectors that fall under this larger category. According to the most recent International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC-4), and according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), the official title for the sector of internal trade is: “Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles.” This general classification includes 43 different subsectors. According to the PCBS 2017 establishment census, the three most prevalent subsectors, which formed 50% of all economic establishments in Palestinian internal trade, were: “Retail sale in non-specialized stores with food, beverages or tobacco predominating,” “Retail sale of food in specialized stores,” and “Retail sale of clothing, footwear and leather articles in specialized stores.” In other words, half of all the economic units in the largest sector in the Palestinian economy were convenience shops, otherwise known as “al-dakakin,” as well as food and clothing retail shops. Data from PCBS National Accounts show that internal trade has played an increasingly key role in terms of its contribution to total Palestinian value-added (i.e. GDP). In 2018, internal trade accounted for 22% of the total Palestinian GDP ($3.6 billion in 2018). This exceeds the contribution of any other economic sector, namely agriculture (7.5%), manufacturing (11.5%), and the broader services sector (20%), which includes education, health, real estate, and other services. Within the private sector alone, internal trade accounts for around 40% of value-added. The fact that internal trade accounts for almost a quarter of total economic activity is not something natural to the Palestinian economy or representative of the skills of its labor force. As graph 1 below shows, the early days of the PA in the mid-1990s witnessed a short-lived period of heightened confidence that contributed to a relatively strong role for manufacturing. However, the years of the 2nd Intifada (2000-2005) curtailed almost all economic sectors except that of public administration, reflecting the increased aid to the public-sector wage bill as a last resort for employment.

Source: PCBS. National Accounts at Current and Constant Prices, multiple years. Ramallah – Palestine.

Source: PCBS. National Accounts at Current and Constant Prices, multiple years. Ramallah – Palestine.

After the 2nd Intifada, a clear pattern started to emerge in 2006 around the neoliberal turn and increased access to credit. Yet despite the neoliberal turn, Palestinian productive sectors either remained stagnant or have declined, while the internal trade contribution more than doubled within 10 years (10% in 2008 to 22% in 2018). This is not surprising given that the neoliberal turn reinforced the primacy of “occupation-circumventing” economic activities that have worked to bypass Israeli obstacles with very little accountability towards the Palestinian people. Productive sectors do not do so since they challenge the status quo of Israeli control over land and borders, which are crucial for agriculture and manufacturing. Still, the contribution to GDP is only one sign of the dominance of internal trade. Since 1997, the PCBS has conducted an overarching census every ten years that has included an establishment census. The census provides data on the number of domestic economic establishments, as well as the number of workers in each of the various sectors and subsectors. Because of its nature, the census does not cover certain economic activities including work in Israel and self-employment. However, the exclusion of Palestinian labor in Israel allows the census to offer a better estimate of the employment created by the domestic private sector. The trends evidenced by the census are revealing. The number of establishments operating in internal trade increased from 39,600 in 1997, to 56,993 and 81,260 in 2007 and 2017, respectively. On average, those figures account for 53% of all economic establishments operating in the Palestinian economy. As mentioned above, and as explained in table 1, three subsectors account for half of that number.

Table 1: The Top Palestinian Subsectors

| Sub-sectors | Number of Establishments | Share of Internal Trade Establishments | Share of all Economic Establishments |

| Convenience shops “al-dakakin” | 17309 | 21% | 11% |

| Food retail shops | 10567 | 13% | 6.7% |

| Clothing retail shops | 10364 | 12.7% | 6.5% |

| Hairdressers and beauty treatment | 8629 | Not part of internal trade sector | 5.5% |

Source: PCBS, 2018. Population, Housing and Establishments Census 2017, Final Results- Establishments Report. Ramallah – Palestine.

As for employment, on average, 37% of all workers covered in the census were employed in the internal trade sector, the highest out of all economic sectors by far, followed by manufacturing (22%). Moreover, the sector was the second highest employer of women (18%), exceeded only by education-related establishments, which employed 26% of all women workers covered in the census. It is noteworthy however, that representation of women in the internal trade sector understates overall participation of women. For example, the 2017 establishment census indicates that while women represented 24% of the total labor force (compared to 76% for men), the internal trade labor force was roughly divided 91% to 9% in favor of men.It is also worth noting that since the private credit boom in 2008, internal trade has been the largest economic sector granted credit facilities and loans, comprising between 20-25% of total private sector credit.1 The amount of credit supplied for internal trade activities increased from roughly $300 million in 2008 to $1,350 million in 2019, a near 350% increase in ten years. The closest sector in 2019 was “residential real estate” loans with roughly $1,050 million. To put this in context, productive sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing made up merely $93 million and $452 million respectively.In addition, Palestinian labor in Israel, which reached more than 40% of the total Palestinian labor force in 1987, has had a dual impact on the demise of productive sectors and the rise of trade-related activities in the Palestinian economy. First, while these Palestinian migrant laborers were paid up to 50% less wages than Israeli workers, their wages were still higher than the average Palestinian salary within the domestic economy. This attracted workers to the Israeli market and artificially pushed domestic wages higher, increasing costs on Palestinian producers. Second, work in Israel created what UNCTAD refers to as the “gap between domestic production and income.” In other words, the income of Palestinian workers in Israel created substantial purchasing power that outpaced domestic productive sectors. The additional income was channeled either to construction or to an ever-increasing level of imports, and the latter led to an unprecedented level of trade deficit.It is clear from the above that internal trade is a leading sector in its contribution to economic output, employment, and personal debt in the Palestinian economy. This indicates a serious blow to Palestinian productive sectors. Understanding how this reality came to be requires an examination of Palestinian economic history that relays the structural distortions created by the Israeli occupation, and the dependency relationship resulting from Israeli colonial economic policies implemented since it occupied Palestine in 1967.

Dependency and Trade in the Palestinian-Israeli Context

Scholars in Latin America were the first to propose dependency theories. One distinct observation they made was that resources, including human resources, natural resources, and other primary goods, were exported from periphery countries in the Global South to center countries in the Global North, while final goods moved in the other direction. As a result, not only did the majority of value-added extraction occur in the center, but also, the economic structure of the periphery was transformed in order to satisfy the needs of the center rather than its own long-term development. This dependency locked periphery economies in a cycle of stunted development whereby they were unable to develop a strong productive base, their trade deficits skyrocketed, and they remained dependent on the labor and goods markets of center economies. In Marxian terms, the center made use of the “reserve army of labor” from the periphery to ensure low costs of production, and opened up the periphery’s markets to its goods in order to guarantee there was no crisis of “overproduction,” whereby firms are unable to sell their commodities because their supply far outstrips existing demand.

Since the establishment of the PA, Palestinian trade has been dependent on Israel for 75% of its imports and 80% of its exports Share on XWith dependency understood in this context, the relationship between the Palestinian and Israeli economies since 1967 offers a textbook example. On the one hand, natural resources (such as land, water, and minerals), unfinished goods, and human resources (labor) moved from the periphery-Palestinian to the center-Israeli economy, while final goods moved from the Israeli to the Palestinian economy.

In the first 20 years of the Israeli occupation, the overall external trade deficit in the Palestinian economy increased from $34 million to $657 million. Moreover, that trade deficit was predominantly the result of trade with Israel, which increased from $100 million to $1.44 billion in those first 20 years. Palestinians exported light manufactured goods and certain types of agricultural produce to Israel, while they imported final consumer goods like durables, which are goods that are not consumed immediately but over a number of years.

This trend did not change after the establishment of the PA in 1994. On the contrary, fueled by international aid and the availability of credit following the 2nd Intifada, the trade deficit reached a peak of $5.5 billion in 2019, with more than half (55%) of that deficit attributed to trade with Israel. As early as the 1980s, more than two thirds of all Palestinian trade was tied to Israel. On average, since the establishment of the PA, Palestinian trade has been dependent on Israel for 75% of its imports and 80% of its exports.

Both imports and exports tell a story of dependency. In many instances, Palestinian imports from Israel were previously produced domestically, including garments, footwear, soft drinks, furniture, and even construction and pharmaceutical goods. Moreover, exports tell a story of entrenched dependency. Since the onset of the occupation in 1967, Israel not only tapped into cheap migrant Palestinian labor, it also exploited Palestinian labor within the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem, including women.

That is, Israeli business people would send raw textiles to subcontracted Palestinian employers who would then hire Palestinian women, paying them low wages. The final products would then be returned to the Israeli business people who would often sell them in Palestinian markets. As a result, many of the items considered to be Palestinian exports to Israel were actually Israeli-connected intermediate output that were later sold back in the Palestinian market as finished and packed goods, in order for Israeli capitalists to gain from the final part of the value chain. In other words, dependency was so entrenched that even the act of exporting was not the outcome of a thriving productive sector, but a result of the power imbalance imposed by Israel on the Palestinian economy, with the vast majority of fruits gained by the Israeli regime.

The Economic Costs of Israel’s Military Occupation

The dynamics outlined above do not only show Palestinians’ entrenched dependency on Israel’s goods and labor market, they also explain how the trade in goods, particularly Israeli goods, slowly became the main economic activity in the West Bank and Gaza. This was partly due to the influx of income from workers in Israel and remittances from Palestinians working in the Gulf, and partly because of the weakening of the productive sectors. However, it was not only these underlying dependency dynamics that boosted internal trade and diminished productive sectors. There was also a concerted effort on the part of the Israeli regime to stifle Palestinian economic activity, while empowering Palestinian traders and merchants. The efforts to curtail Palestinian manufacturing were documented in official Israeli reports. For example, the 1991 report of the Sadan Committee stated that: “No priority was given to the promotion of the local entrepreneurship and business sector,” and that “the authorities discouraged such initiatives whenever they threatened to compete in the Israeli market with existing Israeli firms.”

Since the onset of the occupation in 1967, Israel not only tapped into cheap migrant Palestinian labor, it also exploited Palestinian labor within the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem, including women Share on XIndeed, some of the first military orders issued by Israel were economic in nature, the result of which was to shut down all banks operating in the West Bank and Gaza, and to impose a complex web of administrative procedures and permit restrictions that remain in place to this today. These restrictions have made it virtually impossible for Palestinians to start a business or import new machinery, including for construction. Between 2016 and 2018, the Israeli military authorities approved a mere 3% of construction permits in Area C, which comprises more than 60% of the West Bank. Furthermore, the blockade imposed on Gaza since 2007 has diminished the capacity of Gazan businesses and severely hit its productive sectors, ultimately costing the economy more than $16 billion for the period between 2007 and 2018.

Israel has also controlled Palestinian trade since 1967. While it has allowed some crops and light manufactured goods to enter Israeli markets, these items have been necessary for Israeli manufacturing and food processing, including sesame, tobacco, and cotton. A key part of Israel’s economic strategy has been the “open bridges” policy, which allows unconstrained movement of goods between the east and west banks of the Jordan River. This has been used to “empty” the Palestinian market from certain Palestinian goods to make way for Israeli products, which could not be exported to Arab countries because of the Arab boycott of Israel.

Gradually, the wholesale and retail trade of Israeli products has played a major role in economic activity in the West Bank and Gaza. Since its establishment in 1981, the Israeli military’s “Civil Administration,” which was the sole governing body in the West Bank and Gaza until 1994, and which still maintains control in Area C, has offered cash incentives and bonuses to Palestinian businesses and merchants who agree to export certain products. This not only emptied the Palestinian markets of those products, but was also key for Israel’s foreign currency reserves, as one condition of these incentives was to deposit Jordanian dinar payments in Israeli banks. The “open bridges” policy shifted Palestinian production from satisfying local needs to the production and farming of crops and goods that were intended for outside markets.

By hollowing out the Palestinian market and allowing the unconstrained movement of Israeli goods, the “open bridges” policy created both production and consumption dependencies on Israeli products while bolstering the role of trade among wealthy Palestinian capitalist merchants. Indeed, the owners of large economic establishments and heads of chambers of commerce in Palestinian cities have made fortunes from the occupation. Some of these merchants even acquired franchises and began marketing Israeli goods. Because their interests align with those of Israeli merchants, and as a result of their tendency to appease and negotiate with the occupation regime, they are seen as “the first social class to become linked to the Israeli economy.”

Post-Oslo and the Ongoing Capitulation of Independent Policymaking

The first 25 years of the Israeli occupation hampered the development of Palestinian productive sectors, and focused economic activity on buying and selling imported goods, the vast majority of which were Israeli. After the establishment of the PA in 1994, very little changed in the structure of the economy. Signed agreements, including the Paris Protocol, gave the PA nominal control over fiscal revenues; however, the agreement merely formalized the existing iniquitous customs union between the two economies. Asymmetric price levels continued to hurt both Palestinian producers and consumers since they forced the Palestinian economy to operate under Israel’s high-cost structure, despite the huge disparity in income levels between the two economies. More importantly, the control over borders, resources, and licensing in most agrarian Palestinian land – and land suitable for manufacturing purposes – remains under Israeli control. Productive sectors continue to dwindle and internal trade has become more significant than ever. The Palestinian economic elite have also steered away from productive economic activity that would require challenging the status quo, opting instead to invest in services, finance, and importing. The economic power of the Palestinian capitalists with ties to Gulf countries did not originate in production-related activities. Rather, their profits were “drawn from the exclusive import rights on Israeli goods, and control over large monopolies.”International plans after the 2ndIntifada have fared similarly, including RAND Corporation’s “The Arc” project, John Kerry and the Quartet’s plan in 2014, and, most recently, Jared Kushner’s 2019 plan. While these plans vary in the level of Palestinian involvement and in their sensitivity toward the political situation, they adopt versions of market fundamentalism as opposed to a more nuanced approach to the role of the public sector. For example, the Kushner plan reeks of conservative economic ideologies such as the so-called pro-growth tax structure. It also relies on the principles of the “law and economics” doctrine that drives judicial review of legislation to give priority to orthodox economic ideology over and above moral and legal considerations.

The owners of large economic establishments and heads of chambers of commerce in Palestinian cities have made fortunes from the occupation Share on XTo sum up, the rise in internal trade has led to a shift away from production activity, and toward activities that provide less room for economic development and transformation. There are, however, other social concerns beyond adverse production trends. Women are underrepresented in this segment of the workforce, and the preponderance of internal trade leads to negative distributional impacts within Palestinian society.

One measure of the resultant income inequality can be gauged by the evolution of the wage share, which is the share of total income that is generated from labor, as opposed to the share of total income generated from capital (profit, rent, and interest). While no official series of the wage share exist, one simple measure is to divide the compensation of employees in a sector by the gross value added, signaling a distribution between workers and capitalists. Using this method, internal trade performs worst compared to other sectors, averaging 15% in the last ten years, compared with an average of 27% for all economic sectors.

Conclusion and Recommendations for Ways Forward

There is no one-size-fits-all policy recommendation to remedy the structural distortions in the Palestinian economy that have moved it away from productive sectors. However, the growth of productive sectors should be incubated in a larger frame of developmental economic policy. Fadle Naqib, an expert on the political economy of Palestine, summarizes his three recommendations for the economic sector as follows: Reviving the agricultural sector, expanding the manufacturing sector, and adopting a national strategy for technological development. However, the political realities impacting Palestinian economic development must also be considered. Indeed, in 2010, the World Bank recognizedthat “the long-term development effectiveness of its support is heavily dependent on the Israeli Palestinian political framework,” and, as such, it must “rethink its mandate, role, and scope of activities in the West Bank and Gaza.” The following are recommendations for international financial institutions, including the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, as well as the international community and aid agencies in general, to support Palestinian economic self-determination:

- Recognize that the relationship between the Palestinian and Israeli economies has destroyed any viable development for the Palestinian economy. Indeed, to assume that the dynamics that govern the relationship between the two economies are those of a free market is erroneous and absurd.

- Provide direct international aid to support Palestinian farmers in areas that are facing the threat of annexation, including in areas affected by Israeli settlements and the Wall.

- Pressure the Israeli regime to facilitate licenses in Area C, including building permits for residential and business structures.

- Empower independent Palestinian policy-making by supporting independent research centers and scholars, labor unions, and representatives of groups normally absent from decision-making, including women, youth, and refugees. This must be done with a transparent, accountable, and collective process that includes all Palestinian stakeholders.

- Exert pressure on the Israeli government to end its occupation in order for Palestinians to have control over their own economic policy.

- Recognize that ending the Israeli occupation will also lead to the Palestinian private sector flourishing and thriving.

- This data is from the Palestinian Monetary Authority (PMA) website.

Al-Shabaka policy analyst, Ibrahim Shikaki, is assistant professor of economics at Trinity College, Hartford, CT. He earned his PhD from the New School for Social Research (NSSR) in New York, and held teaching positions at NSSR, The International University College of Turin, Birzeit, and Al-Quds universities. He also held research positions at the Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) in Ramallah and Diakonia’s IHL Research Center in East Jerusalem. His recent writings include an upcoming chapter on the political economy of dependency and class formation in Palestine, and a brief on the economic aspects of Kushner’s Bahrain Plan.