Over recent years, Israel’s impunity has fueled intensifying violence against Palestinians. Israelis killed more Palestinians in 2022 than in any year prior since 2006, and the election of a far-right Israeli governing coalition has led to open and intensifying calls for ethnic cleansing. Meanwhile, the unprecedented expansion of illegal Israeli settlements, skyrocketing attacks by settlers, suffocating blockade of Gaza, and ongoing displacement of Palestinians have continued unabated.1

As the Israeli regime escalates its apartheid and settler colonial practices in Palestine, calls for accountability are mounting. Among these demands are growing calls for sanctions. Still, questions around this tactic remain – both in terms of their ethics and efficacy.

Al-Shabaka spoke with Khaled Elgindy and Nada Elia for further insight on sanctions against Israel. Together, they detail the varied forms that sanctions may take, their potential to affect meaningful change, and distinguish how sanctions targeting the Israeli regime would differ from those wielded by Western powers in other contexts.

The interview below is an abbreviated version of a longer conversation, hosted by US Policy Fellow Tariq Kenney-Shawa in May of 2023. The discussion may be viewed in full here.

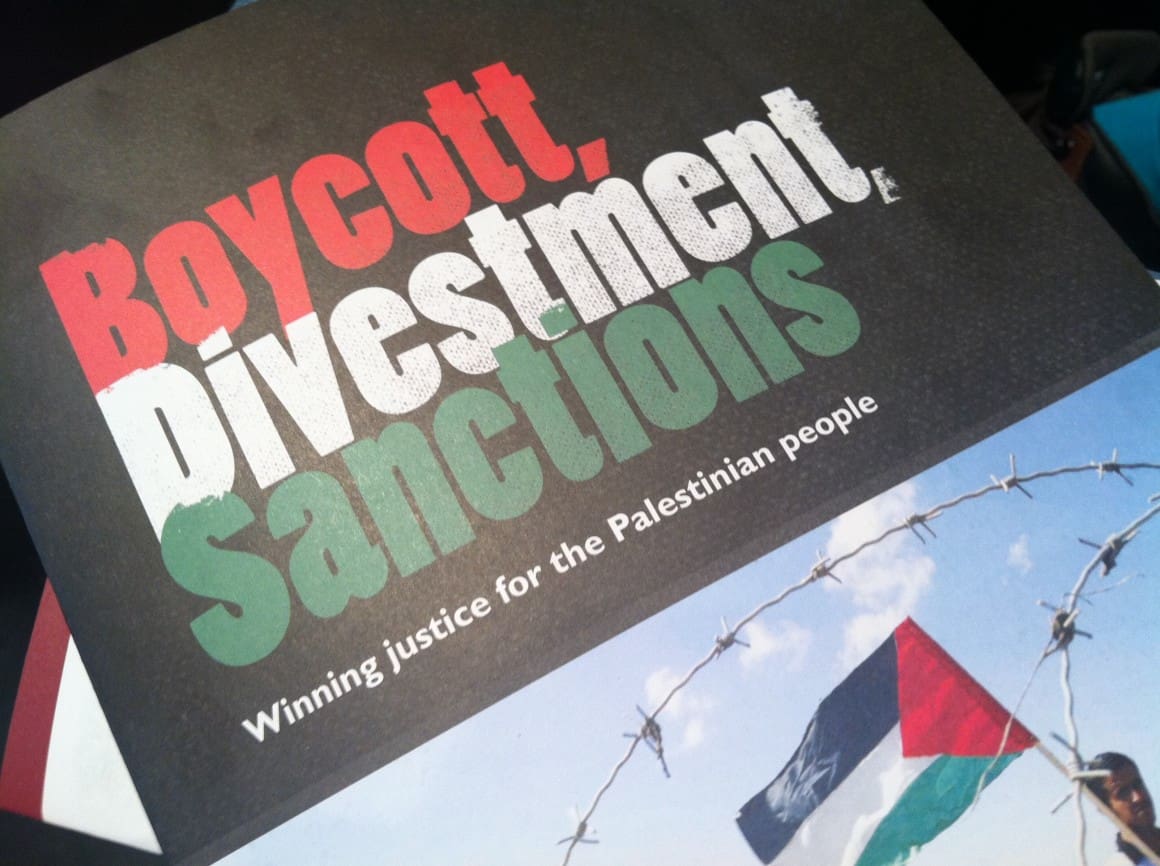

We often discuss sanctions in blanket terms that can obscure their varied forms and application. Nada, when we’re talking about sanctions as a tactic of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) Movement, what exactly would they entail?

Nada Elia

The BDS movement has not specified what type of sanctions should be used against Israel–and rightly so. As a call for global solidarity, it has essentially left the decision up to local organizers to determine what works best, because contexts vary; what makes sense in the US may be different from what makes sense in Italy, for example.

In the US context, sanctions like those imposed on Iraq or on Iran are simply not going to happen. When we think of punitive sanctions and the question of collective punishment, it’s important to understand that sanctions against Israel would not be the same as those we’ve seen in other contexts.

The sanctions against Iraq, for example, were very strict. They were comprehensive economic and trade sanctions that practically banned everything except for humanitarian aid. I cannot imagine the US imposing such sanctions on Israel in either the near or long-term future, even in light of growing recognition of Israel as an apartheid state.

In speaking about sanctions on Israel, we also need to talk about relieving some of the punitive measures, in place for decades, against the Palestinians. Otherwise it's an incomplete discussion Share on X

So, what could US sanctions on Israel look like in practice? I think, realistically speaking, sanctions would include a demand for greater accountability from Israel in how it uses weapons purchased with the $3.8 billion provided in annual US aid. Such a demand would not be insignificant, given that roughly 75% of US aid to Israel is earmarked specifically for weapons purchases.

It’s worth noting that US laws already exist to prohibit the use of military aid by forces engaged in gross human rights violations. It is really a matter of enforcing policies that are already in place. Doing so would send the message that the US is willing to hold Israel accountable for its rights violations. This is a very ethical form of targeted sanctions, distinct from other cases of broad sanctions that are largely ineffective and inhumane. In the context of aid to Israel, it is simply about ensuring that conditions already in place are met.

Public opinion on Palestine is shifting, and the majority of US Democrats now sympathize more with Palestinians than they do with Israelis. There are likewise growing calls for tangible US foreign policy change–including from sitting members of Congress–and many of these calls include conditioning US aid to Israel.

Khaled, do you see the possibility of shifting public support from simply conditioning aid to wider-reaching economic sanctions? If not, what are the political obstacles preventing sanctions from becoming an actual foreign policy reality?

Khaled Elgindy

We are in a very limited realm of what is politically feasible when we talk about any type of sanctions against Israel, perhaps consisting of some aid conditionality and other restrictions.

It is important to point out that, from a policy perspective, official government sanctions on an ally or “friend” of the US are rare. Think about Egypt, for example, and its human rights record. There has been a push by members of Congress, from both parties, for tougher stances on Egypt and other American allies in the region, and it is very, very difficult to get those kinds of sanctions passed. Another example would be Saudi Arabia. After the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, there were many calls for accountability and sanctions. Nonetheless, that special relationship between the US and Saudi Arabia remains almost completely unaffected by his murder.

When we talk about Israel, we’re at a different level of exceptionalism. Israel is the largest US aid recipient in the world. This aid is a central feature of the US-Israel relationship, and it is void of restrictions, conditions, or even scrutiny, in any meaningful way, of the aid that US taxpayers give to Israel on an annual basis. Israel is the only country in the world that receives completely unconditional aid.

Not only is the aid entirely unconditional, but Israel likewise receives a host of special privileges along with it. For example, unlike other military aid recipients, which are obligated to spend US aid on US equipment purchases, aid to Israel may be spent on Israel’s own military industry. This is, of course, in addition to the range of special and exceptional treatments that Israel gets at the economic, political, and diplomatic levels, such as the US veto power at the UN Security Council.

Thus, when we talk about sanctions in relation to Israel, simply withholding any of this special treatment would be considered a sanction. Withholding the US veto at the UN could be a sanction, as could any other action that departs from the current exceptional treatment Israel receives.

The main obstacle to why we haven’t seen any movement, even the most limited type of scrutiny, is that there is a consensus in Washington – in Congress, in the Biden administration, and among most of the analyst community – that is completely opposed to any type of meaningful sanctions on Israel. There isn’t even meaningful oversight, for example through Congressional hearings, on how US aid is being used, on Israel’s human rights record, or on US charities funneling money into Israeli settlements – there is no scrutiny on any of these issues, let alone subsequent action.

In this sense, there is a lot of space in terms of the kinds of policy measures that may be taken, particularly in enforcing existing US laws, such as the Leahy laws and the Arms Export Control Act. These are laws that limit how US military hardware, training, and other types of assistance can be used. Even just applying our own laws, which isn’t being done, can go a very long way in terms of modifying Israeli behavior and achieving some minimal accountability.

There is growing public support in the US for shining a light on Israel’s behavior, given the direction it is moving both in terms of its treatment of Palestinians, as well as in the domestic realm. There’s a lot of trepidation, particularly among rank-and-file Democrats, about this “blank check” that Israel has had for so long.

Still, public opinion is one thing, and politics is another. If public opinion were to dictate politics, we would expect half of Democrats in Congress to support Palestinian rights, but we don’t even see 10%. So, there’s a long way to go in terms of translating public opinion, firstly, into political change, and then into concrete policy change.

Critics of sanctions often argue that they can amount to a form of collective punishment. Is there weight to this critique in the context of Israel? Are there any ethical risks that we should be considering when we call for sanctions?

Nada Elia

No, in my mind there’s a very clear distinction. As Khaled just outlined, none of the possible sanctions the US may take would actually harm the Israeli people. The question is then, should we be concerned about the comfort of our oppressors?

Moreover, there’s a very clear distinction between sanctions imposed upon a people who are already oppressed by their leaders, such as Iran or Iraq, and sanctions imposed upon a country that has repeatedly elected its leaders and supported their policies. In the case of Israel, we see a country – and a people – that has been at ease with the oppression of the indigenous population since its foundation 75 years ago. Imposing the kind of sanctions that we are talking about is simply a form of accountability, a form of consequences. It’s not collective punishment; it does not penalize the people as much as hold them accountable for their political decisions.

Imposing sanctions on a people that support and perpetuate apartheid is a step toward accountability, not collective punishment. It is a step to end Israeli exceptionalism.

Khaled Elgindy

It’s true that sanctions regimes, like those used on Iraq or Iran, are very blunt instruments, and their negative effects tend to go far beyond their ostensible targets. So yes, I think sanctions regimes can be very harmful – and ineffective. In the case of Israel, however, we’re not talking about anything like those kinds of broad-sweeping sanctions, so the question of collective punishment is a moot point.

The irony here is that the only party in this arrangement that is subjected to broad sweeping sanctions by the US are the Palestinians, at every level. The PLO embassy was shut down, as was the US mission to the Palestinians. The US eliminated nearly all forms of aid, thanks to the Taylor Force Act and new laws like the Anti-Terrorism Clarification Act. And of course there are all sorts of other Congressional restrictions on Palestinians, not least of which is representation here in Washington.

Hence, in speaking about sanctions on Israel, we also need to talk about relieving some of the punitive measures, in place for decades, against the Palestinians. Otherwise it’s an incomplete discussion.

What impact would sanctions have on actually affecting Israel’s calculations? Are we expecting too much when it comes to the prospect of coercing Israeli behavior through BDS and calls for aid conditionality?

Khaled Elgindy

Not necessarily. Firstly, it’s important to recall that we’re talking about enforcing existing US laws, not passing new ones. As Nada rightly said, let’s de-exceptionalize Israel. The reality is that going from a place of privilege and exceptionalism to a place of normal normalcy is itself seen as a sanction, as punitive. If you’re accustomed to impunity and special treatment, any retreat from that can feel like a form of oppression.

There are some plausible political steps that the US could take in the coming years. These may include congressional hearings on Israeli policies, the use of US military assistance, official investigations into the murders of US citizens, and merely offering public condemnation of Israel’s human rights abuses. These are all common practices in cases of US support to other nations, and ones that could significantly impact Israel’s behavior.

At the level of the UN, the US could likewise cease its excessive use of its veto power on Israel’s behalf. The US consistently blocks UN Security Council resolutions, even when there’s unanimity otherwise, particularly during Israel’s repeated assaults on Gaza. Withholding that veto could go a long way towards quelling some of the violence.

These actions may not end Israel’s colonial regime in its entirety, but they can mitigate some of the worst aspects on the ground. Blanket impunity from the US matters a great deal to Israel, so I wouldn’t underestimate what the US could do in terms of modifying Israeli behavior.

Nada Elia

It’s important to note as well that calls for sanctions, and BDS more broadly, play a critical role at the grassroots level. BDS is a form of economic activism, yes, but the ultimate goal is not only about making a dent in Israel’s economy. It’s also about shifting public perception.

When we demand sanctions, it is the most direct popular expression of our disapproval of Israel's criminal practices Share on X

When we demand sanctions, it is the most direct popular expression of our disapproval of Israel’s criminal practices. These calls may not impact Israel’s economy, but they can push our representatives to speak out in greater numbers and take action. Political change starts from the grassroots and rises up the ranks of power, so that’s what we’re hoping to achieve with BDS.

Is there a risk to labeling calls for basic accountability and scrutiny as “sanctions”? Might that turn some people away from supporting our struggle?

Khaled Elgindy

I think people – particularly policymakers – are more amenable to positive language versus negative language. I think calls for sanctions and punitive measures generally will turn people off, especially when it comes to Israel.

Conversely, I think talking about accountability is something that resonates with a lot of people. It’s a term that even the Biden administration uses, including in the case of Shireen Abu Akleh’s murder. It’s really the crux of the issue, as sanctions are ultimately about seeking accountability. The core idea is that, when there are consequences for certain behaviors, those who engage in those behaviors will think twice about them. This is the fundamental principle behind accountability, and it’s one that belongs in US foreign policy.

We need to have greater accountability not just of our adversaries, but especially of US allies, starting with Israel. We simply cannot continue to give Israel a blank check and expect its behavior to change. The European Union can and should take similar steps, of course, as should the Arab states now normalizing relations with Israel. There are lots of actions these governments could take to promote baseline accountability with significant effects on the ground.

Nada Elia

I worry that calls for accountability in lieu of sanctions may work to further Israel’s exceptionalization. BDS is a demand for accountability, yes, as well as for de-exceptionalism and the realization of Palestinians’ fundamental rights. Calls for accountability alone may not go far enough, and be used to encourage “constructive engagement” between the US and Israel’s apartheid regime.

At the grassroots level, I believe it is our role to push policymakers to action through rigorous demands and language, and to fully express our censure of Israel’s egregious crimes. We have to be forceful. If the government is going to be cautious about using the term “sanctions,” it is our responsibility to push them forward. So, I still believe in calling for sanctions explicitly, and that doing so will actually help – not hurt – the cause.

- To read this piece in French, please click here. Al-Shabaka is grateful for the efforts by human rights advocates to translate its pieces, but is not responsible for any change in meaning.