- Topics

-

Topics

See our analysis on civil society and how it shapes culture, politics, and policies

Read our insights on the shifting political landscape and what it means for Palestine

Learn more about the policies and practices shaping the Palestinian economy

Strengthen your understanding of the unique conditions for Palestinian refugees across the Middle East

-

- Analysis

-

Analysis

In-depth analysis on existing or potential policies that impact possibilities for Palestinian liberation.

Insights and perspectives on social, political, and economic questions related to Palestine and Palestinians globally.

Concise analysis into a specific policy, its background and implications.

Commentary that brings together insights from multiple analysts.

Compilations of past Al-Shabaka works surrounding a specific theme.

Longer-form, ad hoc projects that seek to confront research questions outside the scope of our regular analysis.

A policy-driven research initiative by Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network.

Our monthly webinar series that brings together Palestinian experts.

Featured

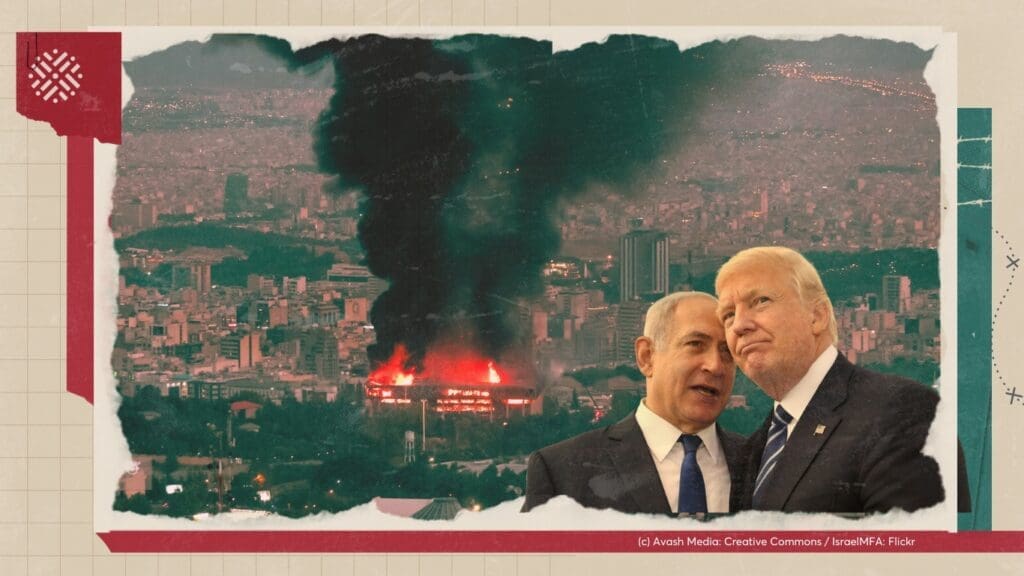

On Thursday, June 19, 2025, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu stood in front of the aftermath of an Iranian strike near Bir al-Saba’ and told journalists: “It really reminds me of the British people during the Blitz. We are going through a Blitz.” The Blitz refers to the sustained bombing campaign carried out by Nazi Germany against the UK, particularly London, between September 1940 and May 1941. With this dramatic comparison, Netanyahu sought to elicit Western sympathy and secure unconditional support for his government’s latest act of military escalation and violation of international law: the unprovoked bombing of Iran. This rhetorical move is far from new; it has become an enduring trope in Israeli political discourse—one that casts Israel as the perennial victim and frames its opponents as modern-day Nazis. Netanyahu has long harbored ambitions of striking Iran with direct US support, but timing has always been central. This moment, then, should not be viewed merely as opportunistic aggression, but as part of a broader, calculated strategy. His actions are shaped by a convergence of unprecedented impunity, shifting regional dynamics, and deepening domestic political fragility. This commentary examines the latest escalation in that context and discusses the broader political forces driving it. Yara Hawari· Jun 26, 2025Launched on May 26, 2025, and secured by US private contractors, the new Israeli-backed aid distribution system in Gaza has resulted in over 100 Palestinian deaths, as civilians navigated dangerous conditions at hubs positioned near military outposts along the Rafah border. These fatalities raise grave concerns about the safety of the aid model and the role of US contractors operating under Israeli oversight. This policy memo argues that the privatization of aid and security in Gaza violates humanitarian norms by turning aid into a tool of control, ethnic cleansing, and colonization. It threatens Palestinian life by conditioning life-saving aid, facilitating forced displacement, and shielding the Israeli regime from legal and moral responsibility. It additionally erodes local and international institutions, especially UNRWA, which has been working in Gaza for decades.

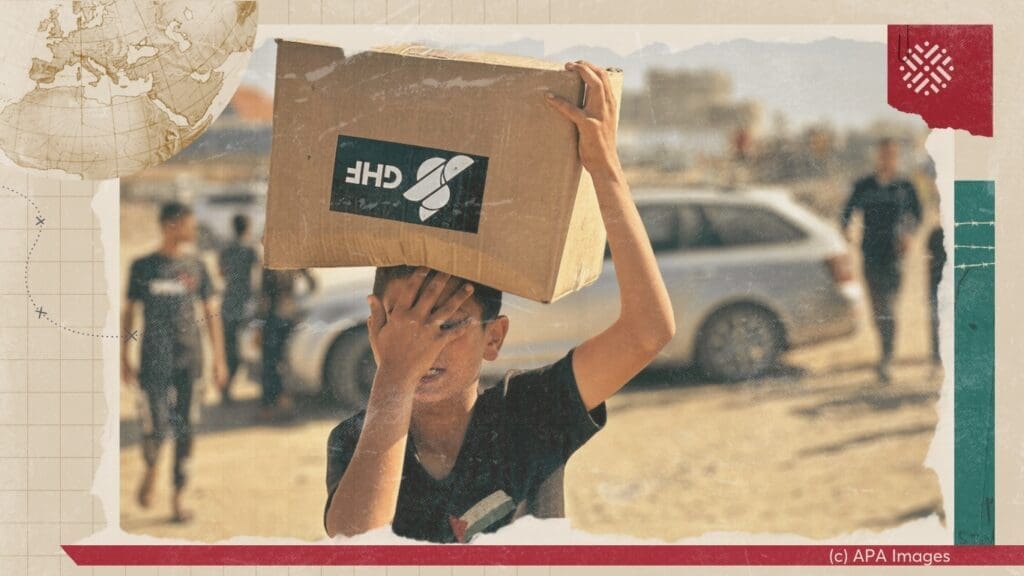

Yara Hawari· Jun 26, 2025Launched on May 26, 2025, and secured by US private contractors, the new Israeli-backed aid distribution system in Gaza has resulted in over 100 Palestinian deaths, as civilians navigated dangerous conditions at hubs positioned near military outposts along the Rafah border. These fatalities raise grave concerns about the safety of the aid model and the role of US contractors operating under Israeli oversight. This policy memo argues that the privatization of aid and security in Gaza violates humanitarian norms by turning aid into a tool of control, ethnic cleansing, and colonization. It threatens Palestinian life by conditioning life-saving aid, facilitating forced displacement, and shielding the Israeli regime from legal and moral responsibility. It additionally erodes local and international institutions, especially UNRWA, which has been working in Gaza for decades. Safa Joudeh· Jun 10, 2025In this policy lab, Mariam Barghouti and Sharif Abdel Kouddous join host Tariq Kenney-Shawa to discuss Israel’s targeted assassination campaign against Palestinian journalists, the complicity of Western media in normalizing these crimes, and how this silence allows Israel to get away with genocide.

Safa Joudeh· Jun 10, 2025In this policy lab, Mariam Barghouti and Sharif Abdel Kouddous join host Tariq Kenney-Shawa to discuss Israel’s targeted assassination campaign against Palestinian journalists, the complicity of Western media in normalizing these crimes, and how this silence allows Israel to get away with genocide. Mariam Barghouti· May 28, 2025

Mariam Barghouti· May 28, 2025

-

- Resources

- Media & Outreach

- The Network

Social Media, Self-Expression, and Self-Determination in Gaza

Introduction

Leadership is a focal point for Palestinians in Gaza who have been living through the division in Palestinian politics since 2007. Palestinian leaders in Fatah and Hamas continue to operate in tandem with the Israeli settler-colonial project to fragment the Palestinian polity, leaving Palestinians in Gaza and elsewhere in colonized Palestine little hope for liberation through the political establishment. Still, youth in Gaza are gaining political awareness through digital activism, particularly on social media platforms.1

This commentary examines the participation of Gaza’s youth in the technological revolution. It offers a critical reading into how this phenomenon has impacted notions of perseverance, social cohesion, and leadership among Palestinians in Gaza. Through an analysis of social media posts on platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, as well as interviews with activists and digital media experts, the commentary highlights the different means through which Palestinians in Gaza express their right to self-determination, to organize, and to restore their political representation in the context of ongoing siege and corrupt leadership.

Gaza’s Technological Revolution

In 2019, the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) reported that less than 1% of Palestinian decision-making positions were held by youth between the ages of 18 and 29. This lack of formal political participation, compounded by repercussions of the Hamas-Fatah division and the Israeli regime’s ongoing siege, has prompted Palestinians in Gaza to begin sharing political views critically and satirically in the digital sphere, and especially on social media platforms.

Palestinian society is young, with one-third of its population under the age of 15. In 2021, 41% of Palestinians in Gaza fell between the ages of zero and 14. Moreover, PCBS reported that 28.7% of Palestinian households in Gaza have a computer, 97.3% have a minimum of one cell phone, and 72.7% have internet access. Ownership of computers, cell phones, and internet services is continually on the rise across colonized Palestine, as are the different skills of digital users. In this upward trend, it is evident that young Palestinians in Gaza are increasingly taking to technology to express themselves and develop digital skills, especially via social media platforms.

Digital Mobilization

Notable political movements and social initiatives that have emerged in Gaza through online campaigns in recent years include the March 15 Movement, the We Want to Live movement, the Ihsan campaign, and the Think of Others initiative:

The March 15 Movement2

The uprisings that spread through the Middle East and North Africa, starting in 2011, inspired Gaza’s youth to call for the end of the division in Palestinian leadership. A group of young digital activists organized a movement named “March 15,” commemorating the date when organizers called on the public to peacefully demonstrate in public squares. The goal of the movement was to end the division and compel Fatah and Hamas to dialogue. However, only one day into the protest, Hamas security forces in Gaza dispersed the crowds, arrested several activists, and surrounded many of their homes.

Social media platforms have enforced political polarization among different segments of Palestinian society and cemented the state of internal political division Share on X

According to the coordinator of the March 15 Movement, more than 90% of their mobilization took place through social media platforms, which was unprecedented at the time. And while political leaders infantilized them, for example, by referring to organizers as “the youth of Facebook and hair gel,” it is undeniable that the movement had significant social impacts in Gaza. Indeed, more than 300,000 demonstrators joined the March 15 protest in Gaza City’s central square.

The We Want to Live Movement

In October 2014, a group of young activists in Gaza launched the We Want to Live Facebook page, with a statement calling on Palestinians in Gaza to take to the streets and demonstrate with kitchenware to express the fundamental nature and objective of the movement: to live. The response was widespread in city squares, villages, and refugee camps, and was bolstered by rising food prices and youth unemployment, which worsened following the Israeli regime’s war on Gaza in the preceding summer. According to activists in the movement, Hamas security forces not only arrested demonstrators in the streets but also activists who were posting on social media.

We Want to Live embodied a qualitative shift in social movements in Gaza in the aftermath of Palestinian political division. The movement formed and developed on social media, with activists exchanging news updates at an unprecedented speed, providing them with the means to express themselves and protest the detention campaign to which demonstrators were subjected. Digital communication likewise allowed for better safety monitoring among campaign activists. Indeed, the online tools became such a perceived danger to the status quo that security forces reportedly threatened to ban Facebook in Gaza, and conditioned detained activists’ release on erasing posts regarding the movement and general living conditions in Gaza.

Voluntary Social Initiatives3

Since the Hamas-Fatah division in 2007, and the subsequent Israeli siege and successive Israeli attacks on Gaza, several voluntary initiatives have emerged with growing impact. Youth-based humanitarian initiatives in Gaza are active through social media accounts, responding to appeals for help on Facebook, for example, through the provision of food parcels or monetary assistance. These initiatives serve marginalized communities, most of which do not benefit from government or civil society assistance programs, according to those in charge of the initiatives.

The Ihsan campaign is a voluntary civil society initiative in Gaza that provides food packages, clothing donations, and school supplies, among other items, to communities in need. Launched in 2011 by a team of young volunteers through social media channels, this campaign operates across Gaza and has a strictly non-partisan platform, including in its sources of funding. Think About Others is a similar initiative that helps poverty-stricken communities, especially with food distributions. However, according to activists, these and several other initiatives face obstacles, notably the lack of funding and the dearth of donations from within colonized Palestine and abroad.

Technology and Social and Political Action in Gaza4

Interviews with researchers, journalists, and media experts indicate three overarching repercussions of the technological revolution in Gaza on youth activism:

1. The extent to which social media platforms can be used for political organization and leadership, as well as a tool for self-determination, remains questionable.

While there are examples of successful organizing through social media, such as the solidarity campaigns with Sheikh Jarrah and groups like the al-Habd Electronic Army, which target anti-Palestinian and Zionist posts on social media, this type of organizing is often circumstantial, improvised, and temporary, responding to events occurring on the ground. As such, if new and more concerted campaigns emerge, previous ones fade away. More sustained, transformational organizing necessitates substantive coordination and mass communication.

Furthermore, much of the engagement that these movements make through their digital presence remains limited to the provision of information rather than active mobilization of new audiences, limiting their ability to expand. As a result, many of these campaigns do not last, and therefore cannot be envisioned as tools for achieving self-determination.

2. The degree to which social media can strengthen Palestinian social fabric is unknown.

Social media can play a positive role in promoting social cohesion by facilitating communication between Palestinians across colonized Palestine and beyond. Many of these platforms have enabled Palestinians to come together at crucial times to protest, for example, the Israeli regime’s assaults on Gaza, and to express solidarity with the Palestinian residents of Sheikh Jarrah, among others. Moreover, social media platforms provide Palestinians with the space to circulate critical content about their leadership, albeit not without risk.

Palestinians in Gaza will continue to suffer under their leadership unless technological advancement is coupled with collective social and political mobilization, especially among younger generations Share on X

Still, aggression is on the rise among Palestinians on social media, especially between those in Gaza and the West Bank. Social media platforms have enforced political polarization among different segments of Palestinian society and cemented the state of internal political division. By extension, they have exacerbated the differences between activists to extreme degrees. Indeed, these channels are widely used to slander influential individuals, driving many political figures to monitor their opponents online. This has resulted in further social and political fragmentation, and increased online harassment. Some attribute this situation to a lack of regulations that limit cybercrimes and sexual harassment. How can one expect social rapprochement while political positions are fundamentally divided?

3. Despite hardships, Palestinians continue to seek their right to engage politically. But how beneficial is individual expression on social media?

Social media platforms have provided ample space for political engagement, enabling Palestinians in Gaza to express themselves despite many obstacles and security threats, including the potential of being held legally accountable by the de facto government for criticizing the political or economic status quo. But for the most part, youth in Gaza use social media to reflect on their daily lives, and to express their sense of loneliness and despair in the face of oppressive leadership and the Israeli regime’s suffocating siege.

Indeed, a close read of social media posts among Palestinians in Gaza indicates that youth have been using social media to express the uniqueness of their daily lives in isolation from the overarching Palestinian cause. This is evidenced by the extensive use of the terms “Gazan” and “West Banker” as opposed to Palestinian. However, this does not necessarily indicate that Palestinians in Gaza are separating themselves from the larger Palestinian national identity. Rather, instances of distinguishing between Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank should be understood as a way to highlight to the world the specific and ongoing injustice to which Palestinians in Gaza are subjected on a daily basis.

Conclusion

As Palestinians in Gaza continue to lose hope in the prospect of political change at the level of their leadership, digital protest has given them a new venue for social and political expression. Indeed, the March 15 and We Want to Live movements have garnered local and international attention among Palestinians and their allies, in great part due to their existence in the digital sphere.

But the technological revolution has also allowed for a type of individualism that hampers collective social and political action. While different initiatives like the Ihsan and Think About Others campaigns have been relatively successful in providing services to marginalized communities, and while social media enabled these and other initiatives to reach across Gaza and beyond, they also lack the power and persuasiveness that direct, personal engagement possesses.

Thus, it remains difficult to determine the role that social media can play within the Palestinian struggle for liberation from Israeli colonization and from corrupt leadership. What is clear is that Palestinians in Gaza will continue to suffer under their leadership unless technological advancement is coupled with collective social and political mobilization, especially among younger generations.

Ali Abdel-Wahab

Latest Analysis

Timed for Impunity: Israel’s War on Iran

Outsourcing Occupation: US Private Contractors in Gaza

Israel’s War on Palestinian Journalists

We’re building a network for liberation.

As the only global Palestinian think tank, we’re working hard to respond to rapid developments affecting Palestinians, while remaining committed to shedding light on issues that may otherwise be overlooked.