- Topics

-

Topics

See our analysis on civil society and how it shapes culture, politics, and policies

Read our insights on the shifting political landscape and what it means for Palestine

Learn more about the policies and practices shaping the Palestinian economy

Strengthen your understanding of the unique conditions for Palestinian refugees across the Middle East

-

- Analysis

-

Analysis

In-depth analysis on existing or potential policies that impact possibilities for Palestinian liberation.

Insights and perspectives on social, political, and economic questions related to Palestine and Palestinians globally.

Concise analysis into a specific policy, its background and implications.

Commentary that brings together insights from multiple analysts.

Compilations of past Al-Shabaka works surrounding a specific theme.

Longer-form, ad hoc projects that seek to confront research questions outside the scope of our regular analysis.

A policy-driven research initiative by Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network.

Our monthly webinar series that brings together Palestinian experts.

Featured

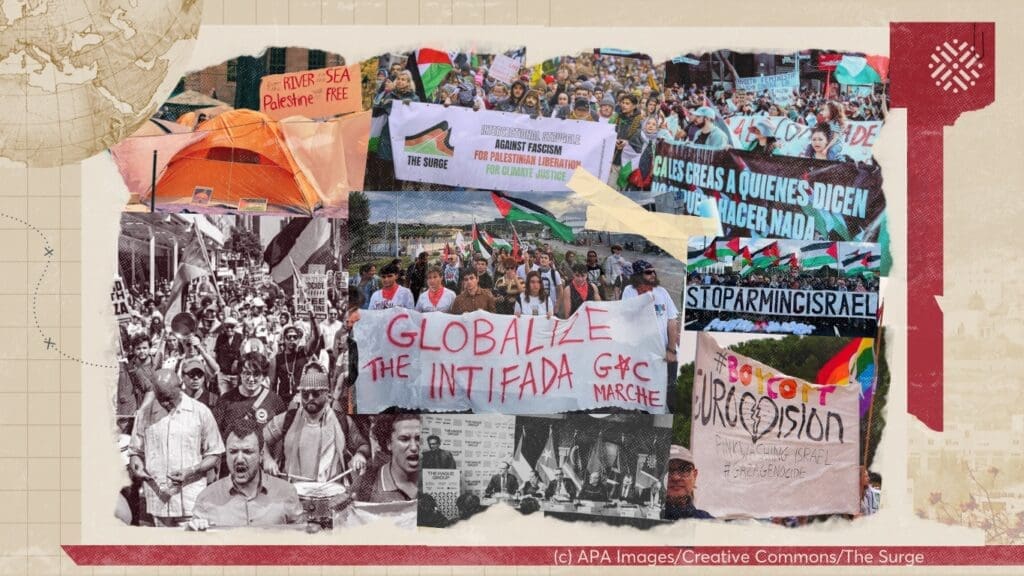

The global reckoning that followed October 7, 2023, marked a profound rupture in how Palestine is understood worldwide. The Gaza genocide exposed how Israeli mass violence is not exceptional or reactive, but foundational to the Zionist project. What was once framed as a “conflict” to be managed is now widely recognized as a system of domination to be dismantled. It ushered in a shift away from the technocratic language of peace processes and toward an honest confrontation with the structural realities Palestinians have long named: settler colonialism, apartheid, and the ongoing Nakba. The commentary argues that the Israeli genocidal campaign in Gaza has radicalized the world. When crowds march through global capitals demanding a free Palestine, they simultaneously articulate demands for the abolition of racial capitalism, extractive regimes, climate injustice, and all forms of contemporary fascism. In this moment of radical clarity, Palestine becomes a lens through which the underlying architecture of global domination is laid bare—and through which new horizons of collective freedom emerge. Tareq Baconi· Dec 21, 2025Inès Abdel Razek and Munir Nuseibah joined Al-Shabaka for a conversation on the politics behind the UNSC resolution, the implementability of the US-Israeli plan, and the scenarios now being advanced for Gaza and for Palestine more broadly.

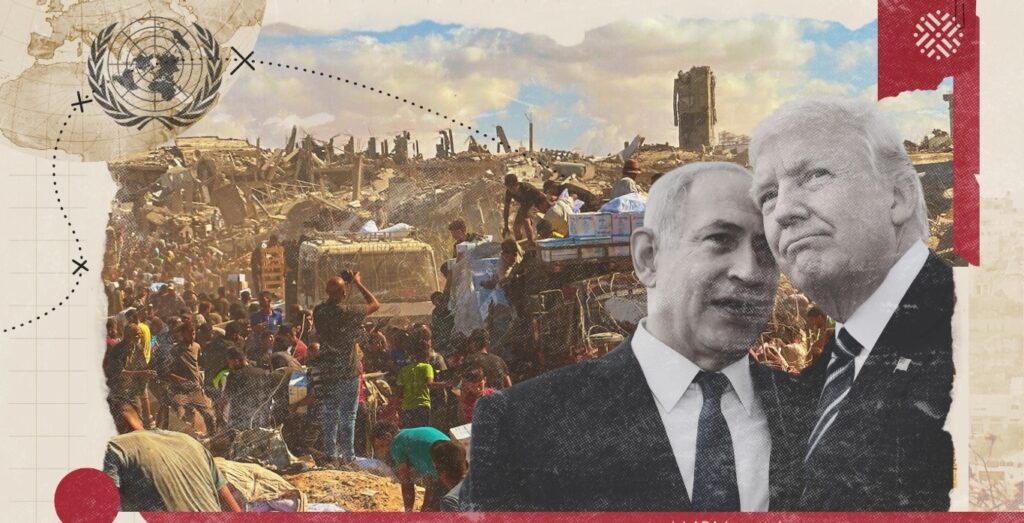

Tareq Baconi· Dec 21, 2025Inès Abdel Razek and Munir Nuseibah joined Al-Shabaka for a conversation on the politics behind the UNSC resolution, the implementability of the US-Israeli plan, and the scenarios now being advanced for Gaza and for Palestine more broadly.

European empires used Christian missions to legitimize conquest in Africa and advance imperial interests, laying the groundwork for a political form of Christian Zionism. British evangelicals were central in transforming Christian Zionism from a theological belief into an imperial strategy by promoting Jewish resettlement in Palestine as a means of extending British influence. This fusion of religious ideology and imperial ambition endures in contemporary Christian Zionist movements, which frame modern Israel as the fulfillment of biblical prophecy and recast Palestinian presence as an impediment to a divinely ordained order. This policy brief shows how these narratives and their policy effects have taken root in the Global South, including in South Africa. In this context, Israeli efforts increasingly rely on Christian Zionist networks to weaken longstanding solidarity with Palestinians and cultivate support for Israeli occupation.

European empires used Christian missions to legitimize conquest in Africa and advance imperial interests, laying the groundwork for a political form of Christian Zionism. British evangelicals were central in transforming Christian Zionism from a theological belief into an imperial strategy by promoting Jewish resettlement in Palestine as a means of extending British influence. This fusion of religious ideology and imperial ambition endures in contemporary Christian Zionist movements, which frame modern Israel as the fulfillment of biblical prophecy and recast Palestinian presence as an impediment to a divinely ordained order. This policy brief shows how these narratives and their policy effects have taken root in the Global South, including in South Africa. In this context, Israeli efforts increasingly rely on Christian Zionist networks to weaken longstanding solidarity with Palestinians and cultivate support for Israeli occupation. Fathi Nimer· Dec 7, 2025

Fathi Nimer· Dec 7, 2025

-

- Resources

- Media & Outreach

- The Network

PA Industrial Zones: Cementing Statehood or Occupation?

The Palestinian Authority (PA) began to establish export-oriented industrial zones when it was created some two decades ago, partly in response to donor recommendations and partly in line with the neoliberal policies it was introducing. Thus, Palestinians have been hearing for years about Turkish-German, Japanese and French industrial parks in Jenin, Jericho and Bethlehem, respectively, but, tellingly, they have rarely heard these described as Palestinian.

The debate about the zones, also known as parks, is polarized. The PA, its international sponsors, and the PA-dependent private sector see the industrial zones as a pillar of the state-building effort that will bolster the Palestinian economy and achieve sustainable development.

The zones’ critics argue that they reinforce and legitimize the occupation by making the Palestinians even more subservient to Israel given that the PA has to rely on the occupiers’ good will for access, movement and for transfer of tax revenues. In addition, the zones give Israeli companies a legal way to penetrate the Palestinian economy.

Moreover, the zones distort the Palestinian economy by ignoring its natural advantages, such as tourism and its related industries, as Sam Bahour describes in a compelling piece. They also override the imperative of resisting the occupation to win self-determination, freedom, justice, and equality. This imperative requires an entirely different kind of economic policy, one that is less vulnerable to Israeli control by being based on small-scale agriculture and industry targeted primarily at the local market and by fostering economic steadfastness rather than export-led growth. Al-Shabaka has argued for this approach in pieces on farming, growth, the resistance economy, and alternative approaches to aid, among others.

The Jericho Agro-Industrial Park (JAIP) initiated in 2006 and supported by the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) to the tune of $47.7 million is a stark illustration of the problems with industrial zones. A full discussion of the issues is set out in a study published by the Bisan Center for Research and Development in September 2012, as well as in a position paper by this author published by Bisan in December 2012. This commentary, which draws on the fuller study, takes forward two themes, the lack of public accountability and the role of donor-driven aid.

The Palestinian Industrial Estate and Free Zone Authority (PIEFZA) sets out the official purpose of the JAIP project. It is to “enhance the philosophy of steadfastness and defiance” based on a simple economic philosophy of attracting foreign investment, exporting manufactured products, creating local job opportunities, and improving the GDP.[fn]Interview with the author September 30, 2012[/fn]

However, these official claims paper over several issues that cry out for public accountability. For example, there are major problems with the feasibility studies which have been criticized by many sources, including PIEFZA project managers, and which include inaccurate and exaggerated numbers and no clear and transparent financial reports or budgets.[fn]These conclusions are based on interviews conducted by the author with the Japanese official responsible for the project as well as with PIEFZA staff and former staff between September 30 and October 2.[/fn]

According to the official view, JAIP differs from other Oslo-designed projects because it is located deep inside Palestinian land rather than on the border with Israel, as was the case, for example, with the now defunct Erez Industrial Zone. But this is naive, to say the least. How can one refer to something as being deep inside Palestinian territory when Israel controls Palestinian borders and is, furthermore, rapidly colonizing the Jordan Valley?

Much more problematically, a report by Stop the Wall quoted a preliminary JICA document that appeared to propose providing direct support to and benefiting from the Israeli settlements in the Jordan Valley – euphemistically described as “Israeli migrant firms” – despite the flagrant illegality of Israel’s settlement enterprise. The JICA project did not even comply with the Oslo Accords, Paris Protocol, and Agreement on Movement and Access – bad as these agreements were for the Palestinian people – according to the Negotiations Support Unit advising the Palestine Liberation Organization, which opposed the project, according to the Palestine Papers.

The Guardian describes the Japanese purpose in launching their “corridor for peace and prosperity” in the Jordan Valley as to encourage cooperation between Israel, the PA, and Jordan.

This goes directly to the heart of the problem: How can there be cooperation between the occupier and the occupied until the occupation is over and the Palestinians are able to exercise sovereignty? The fact that there is no agreement yet on the third phase of the project, which is supposed to be located in areas classified as “C” under the Oslo accords, underscores this point. As is well known, Israel is also rapidly colonizing and depopulating Area C, which covers over 60% of the West Bank, and not only preventing but also destroying donor and PA projects there.

Even at the most basic level, public accountability is missing in this initiative. The feasibility studies, reports, important strategic papers, and financial records are not publicly available in Arabic, and the Arabic website simply contains some brief progress reports. The availability of materials in the national language is a minimum for national ownership of a donor-supported project, as recommended by the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, to which Japan and the PA say they subscribe.

Publicly accessible information is not only important for the Palestinian public. It is also important to justify this aid to Japanese taxpayers so that they know whether their contributions are actually good for the Palestinian people or not. One would assume that the Japanese public would be concerned about the fact that the initiative for the project came from Japan despite the mixed record, to put it mildly, of development assistance in the OPT and particularly industrial zones, and the fact that the project is still struggling after six years of work, largely due to the obstacles Israel has put in its way.

Besides, JICA is one of the “cooperation agencies” that often retains its funds for itself or funnels them back to Japan directly and indirectly by using Japanese experts, goods, and services. For example, the extensive solar system installed in the project is Japanese from A to Z: donor, contractor, consultant, provider, and installer. It would actually be more correct to describe Japanese funds as investment, rather than aid. The purpose here is not to single out Japan for criticism but to draw attention to the problems with much of the donor aid to the OPT.

Beyond the issues specific to the Palestinian context, there are problems with industrial zones in the region and around the globe, which include exploitation of workers, pollution, and siphoning of funds away from the national economy. These should also be the subject of public debate in the OPT. Bahour’s study gives as an example the Jordan Qualified Industrial Zones established after the Israeli-Jordanian peace agreement in 1994. Not only did that initiative, promoted by the United States in both Jordan and Egypt to “promote” peace, open doors to Israeli penetration of the Jordanian and Arab economies, the zones barely created jobs for Jordanians: 75% of the jobs are carried out by foreign workers.

The bottom line is clear. JAIP is yet another example of avoiding the roots of the problem facing the Palestinian people. It was not built to challenge the occupation and colonization and decades-long denial of rights, but rather to impose an economic peace between the colonizer and the colonized. This reality cannot be masked by talking of profits, economic efficiency, and other technical jargon.

Palestinian civil society must advocate for a national consensus regarding Israel’s role in projects such as JAIP. To state the obvious, it makes no sense to deal with Israel as both a partner and colonizer and the intricate joint network of businesses and relationships with Israel must be dismantled as soon as possible. There is also a pressing need for Palestinian civil society to demand accountability for both individual projects and the overall development approach.

There is an important role for the Palestinian youth movement to play here in collaboration with independent civil society organizations. Such a role should not only challenge the glaring mistakes of the past, but also go beyond these to redefine development in the Palestinian context as a process that leads to freedom and rights.

No one is arguing against the need to support the Palestinian ability to survive and develop under occupation until they can achieve self-determination. But it is becoming ever more evident that if Palestinians do not ensure dignity in their development no one else will do it for them. The Palestinian people must always keep in view Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s powerful words, “I am not interested in picking up crumbs of compassion thrown from the table of someone who considers himself my master. I want the full menu of rights.”

For further information on this subject, see the position paper that Alaa Tartir prepared for the Bisan Center for Research and Development, Jericho Agro-Industrial Park: A Corridor for Peace or Perpetuation of Occupation? (PDF).

Alaa Tartir

Latest Analysis

The World Radicalized by the Gaza Genocide

Legitimizing Genocide: The Israel-Trump Plan and Gaza’s Future

Christian Zionism in the Global South: The Case of South Africa

We’re building a network for liberation.

As the only global Palestinian think tank, we’re working hard to respond to rapid developments affecting Palestinians, while remaining committed to shedding light on issues that may otherwise be overlooked.