About This Episode

Episode Transcript

The transcript below has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

Tareq Baconi 0:00

I think the Palestinian struggle is also ongoing — in the sense that its understanding now, in this 21st-century reality we’re living in, that there are new forms of mobilization that can reshape an alternative phase of Palestinian liberation that is rooted in the power of the people. And the Great March of Return, for me, is the biggest example of that.

Yara Hawari 0:27

This is Rethinking Palestine, a podcast from Al-Shabaka, the Palestinian Policy Network. We are a virtual think tank that aims to foster public debate on Palestinian human rights and self-determination. We draw upon the vast knowledge and experience of the Palestinian people, whether in Palestine or in exile, to put forward strong and diverse Palestinian policy voices. In this podcast, we will be bringing these voices to you so that you can listen to Palestinians sharing their analysis wherever you are in the world.

This has been quite a year globally, and in particular for vulnerable and oppressed peoples. In Palestine in particular, beyond the pandemic, we’ve seen further entrenchment of Israeli domination over Palestinian lives, with a huge boost from US foreign policy, as we discussed in our last episode.

But we also saw, yet again, a failure from the Palestinian leadership to provide a challenge to the Israeli regime on the ground and in the international arena, and to unite an increasingly socially, geographically, and politically fragmented people.

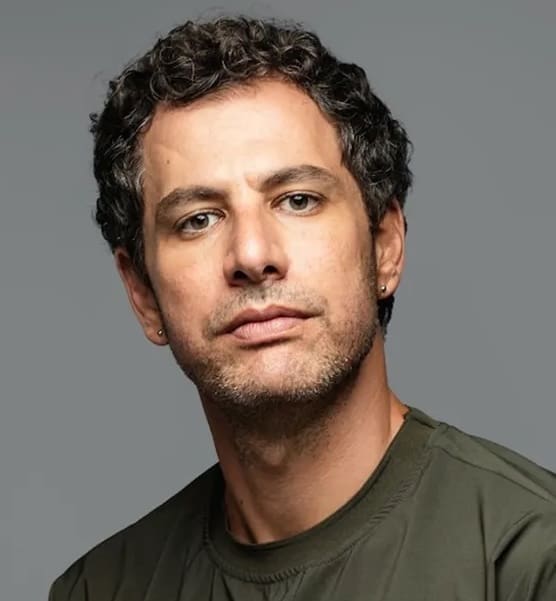

To discuss all this and more, I’m joined by Dr. Tareq Baconi, board member for Al-Shabaka and author of the book Hamas Contained: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance. Tareq, thank you for joining us.

Tareq Baconi 1:49

Thank you for having me.

Yara Hawari 1:50

Perhaps we should start with COVID-19 as the defining global event of 2020. What did COVID-19 highlight in Palestine, particularly vis-à-vis the Palestinian leadership and the Palestinian people themselves?

Tareq Baconi 2:03

Well, it was actually quite an interesting development, in the sense that it showed many of the observers that are watching this space something that many Palestinians have been arguing for some time, which is that Palestinians are living in a one-state reality in this space that’s officially, or often referred to as, “Israel-Palestine.”

The reality is that, even though many international observers look at this space as one where there’s an Israeli state and a State of Palestine that’s under Israeli occupation, what COVID-19 and the pandemic showed us is that actually this idea that the State of Palestine — or the Palestinian Authority specifically in the West Bank — is the embryo of a future state was really dismantled and deconstructed. And the reality that we saw is one where the Palestinians were, in every way, subject to Israeli sovereignty.

And I’m going to unpack that so that I explain a bit more what I mean. So, when the pandemic obviously hit different countries all around the world, sovereign governments took measures that are related to whether their populations are able to travel, socialize, come in and out of the country, how the health sector was able to respond to the crisis that was unfolding, whether the country would be able to get a testing kit — all of those decisions were made on the level of governments.

In Israel-Palestine, even though ostensibly the Palestinian Authority would be the body that would be making some of these health decisions, the reality was that the Palestinian response to the pandemic was limited to Israeli sovereign decisions. So what determined what kind of medical supplies and equipment were able to enter into the Palestinian Territories, who was able to enter into the Palestinian Territories, who was able to leave — all of those sovereign questions were made by the Israeli government, with no input from the Palestinian leadership.

In the early days of the pandemic, we saw all forms of engagement between the Israelis and the Palestinians being celebrated by UN observers and other international observers as a form of cooperation. But rather than cooperation, which denotes this idea that there are two sides cooperating on an equal footing, the reality was that the Palestinians were demoted to ensuring the implementation of Israeli policies — whether with regards to travel or even lockdown — within the Palestinian Territories, subject to Israeli sovereign decisions.

And I’m just going to give a couple of examples here. So, for example, with the epicenter of the pandemic being in Bethlehem in the West Bank, the policies that prevented people from mixing or interacting within Bethlehem were subject to monitoring by the Palestinian Authority. But outside of Bethlehem — let’s say, travel between Bethlehem and other cities in the West Bank, including Ramallah — all of that, under the control of Israeli security forces in Area C, was all subject to Israeli decisions, in terms of determining the mobility of people throughout the West Bank.

And more importantly, in terms of the entry of medical supplies and testing equipment, that was all subject to Israeli decision-making. And we see that, obviously to an extreme, in the Gaza Strip, where all forms of medical supplies are subject to Israeli whims. At present, we see that in vaccines — that Israel is able to get loads of vaccines delivered to its doorstep and to its citizens, and those are only given to Israeli citizens and not to the Palestinians under their control.

So in summary, what the COVID-19 pandemic has shown is that there is only one sovereign, one decision-making body within Israel-Palestine, and that’s the state of Israel. And the Palestinians, even with their pseudo-institutions of state — what the international community views as the embryo of a state — is actually just a glorified municipality working under Israeli authority.

Yara Hawari 6:03

Thank you, Tareq, for that. I think that COVID-19 not only highlighted this issue of sovereignty, or lack of Palestinian sovereignty, but also the fragmentation aspect. Palestinians really have never been more fragmented — geographically, socially, politically, etc.: the West Bank, which in itself is divided into Areas A, B, and C; Gaza, which is totally cut off; the Palestinian citizens of Israel; the Palestinian refugees and those in diaspora.

And I think it’s important to note that this is by design. If you fragment a people from one another physically and geographically, it’s easier to divide them socially and politically. And indeed, the infamous ESCWA report, compiled by Richard Falk and Virginia Tilley, notes that this is one of the main mechanisms by which Israeli apartheid is maintained. And of course, Palestinians are also divided along lines of class and gender.

How has all of this fragmentation affected the Palestinian struggle for liberation?

Tareq Baconi 7:08

Well, predominantly by completely undermining its capacity to speak in a single voice and undermining the capacity of Palestinians writ large to view their struggle as being one against a single foe, which is Israeli settler colonialism in the land of historic Palestine — or what we would think of as the manifestation of Zionism in the land of historic Palestine.

That fragmentation has prevented Palestinians from understanding their struggle as being a single struggle encompassing all different forms of Palestinianness, whether by class or gender or geography, as actually being part of a single struggle against a single foe. And instead, what it’s done is created bubbles of local struggle, where Palestinians are focused on immediate concerns or immediate life-threatening realities, rather than understanding and mobilizing in a way that presents their struggle against Israeli control.

And so, for example, a Palestinian in the Gaza Strip is worried about whether they are able to ever leave the Gaza Strip, is worried about living in an enclosed space under Israeli military assault. Someone in the West Bank might not be able to even begin to associate with what that fear looks like, with what that kind of enclosure on one’s life feels like. And so the reality becomes that someone in the West Bank and someone in the Gaza Strip are living in almost completely different universes, and each one of them would think of their struggle in different ways.

For someone in the West Bank, they’re worried about being caught at a checkpoint, or having their home demolished, or having to face an Israeli incursion into their city or their village or their refugee camp. The Palestinians living in Yarmouk in Syria had their existential crisis of living in what became a war zone and having to live another generation of exile and dispossession.

And so the reality that’s been created is that each Palestinian community, or each Palestinian identity, becomes enshrined in its own existential struggle. And that overrides that single struggle that unites all of us against Israeli settler colonialism.

And unfortunately, because of the decisions that the Palestinian leadership has taken historically, beginning with the acceptance of the idea of partition of the land of historic Palestine, that fragmentation into ever-smaller enclosures and ever-smaller struggles continues and continues. So now the Palestinian struggle is really operating on the terms of debate set by Israel and by Zionist settler colonialism, rather than by the Palestinian terms of debate, which is the right of return, and the right for decolonization of historic Palestine, and the right to go back to a reality where Palestinians are not under military occupation.

So I think the reality of fragmentation is one that all Palestinians feel, and I think that it manifests maybe most clearly physically, in that Palestinians are all over the world and, even in the West Bank, living in different enclaves. But it also represents itself in terms of identity. A Palestinian in the West Bank might view themselves as different from Palestinians in Gaza, because they can’t quite relate to the vastly different experiences they live in. And that has longstanding implications for our understanding as a people.

Yara Hawari 10:55

Tareq, I want to return to Gaza, because I know you’ve written much about Gaza and indeed a lot of your academic research focuses on this particular part of Palestine.

Now, we consistently see plans presented to Palestinians where their fundamental rights are totally disregarded in exchange for what is called “Israeli security,” and this was epitomized this last year by the Trump plan. But we also see consistently Gaza being siphoned off, ignored, and essentially being treated as separate to the rest of Palestine.

Why is this, and what has it meant for the role of Gaza in the Palestinian struggle?

Tareq Baconi 11:37

I think that’s an excellent question. And I think that, as Palestinians and as academics and scholars and policymakers engaged in this space, our mission is to always ensure that Gaza is brought back into the conversation on Israel-Palestine. Because you’re absolutely right, in the sense that it’s often marginalized or exceptionalized, held in a space of exception as if it’s separate from the Palestinian question.

To my mind, and in all of my academic work and my writing, I’ve actually come to the realization that Gaza is the linchpin of Palestine. It is exactly the core that needs to be liberated and decolonized in order for the Palestinian question to also reach a stage of justice and freedom. And the reason I say that is because the reality that is the Gaza Strip today, as I see it, is the extreme function — it’s the endpoint — of where Israeli settler colonialism in the land of historic Palestine is going. It shows the endpoint of that trajectory.

So what do I mean by that? First of all, we need to understand that the reason for Gaza’s isolation is predominantly demographic. The two million Palestinian inhabitants of that strip of land would jeopardize the Jewish majority that is seen between the river and the sea, if it were to be encompassed into that discussion of Israel-Palestine. So almost existentially, for those who declare Israel to be a Jewish state, the Gaza Strip has to be removed for Israel to continue maintaining its Jewish majority without giving up its control over the West Bank.

The second reason that Gaza has to be marginalized is because of the fact that the majority of these inhabitants are refugees. So the right of return there is something that is felt and real. And the combination of those two realities is how Gaza has historically also been the source of resistance — the bedrock of Palestinian resistance to Israeli domination in this land, beginning from 1948 onwards, and even before 1948.

The scholar Jean-Pierre Filiu has talked about how, since 1948, Israel has waged more than twelve wars on the Gaza Strip in order to try to subjugate or remove this ember of resistance from the Gaza Strip. And of course, the blockade and the military assaults that Israel continues to carry out on the Gaza Strip is the most contemporary manifestation of that effort to pacify the Gaza Strip.

Often we hear this — in the policymaking community certainly — that this blockade is a response to Hamas, that it’s a security reality. When actually, this is a continuation of Israeli policies that stretch back to the earliest days of the state, and the blockade itself actually also predated Hamas. In some ways, as I argue in my own work, Hamas is the faculty that justifies Israeli policies.

So the way that I view the Gaza Strip is to see it as the extreme manifestation of different urban enclaves where Palestinians are enclosed throughout the land of historic Palestine. So to my mind, the Gaza Strip is the extreme of any Area A in the West Bank; it’s the extreme of East Jerusalem; it is the extreme version of Palestinian communities being hemmed in by Israeli systems of control and surrounded either by Israeli territory or Israeli-controlled territory, such as Area C in the West Bank.

So the Gaza Strip, if it’s taken as that standalone bubble — rather than a state of exception, it’s actually exactly what the endpoint of Israeli settler colonialism looks like in historic Palestine, which is Palestinians enclosed in urban communities surrounded and controlled by Israeli territory and Israeli settlements. We see it in the Galilee and we see it in the Gaza Strip. And obviously there are different modes of what that system of control looks like, but fundamentally the structure of control is the same, which is that Palestinians are unable to move in and out of those territories outside of Israeli will.

So what we have in the Gaza Strip, I think, is the blueprint for us to see what Israel intends to do in terms of the trajectory of its settler colonialism in the land of historic Palestine. And in that way, it’s not an exception. So we need to, in our own thinking and in our own writing, resist this fragmentation — that the Gaza Strip is a state of exception — and actually understand it as a linchpin of Palestine.

Yara Hawari 16:31

If you’re enjoying this podcast, please visit our website, al-shabaka.org, where you’ll find more Palestinian policy analysis, and where you can join our mailing list and donate to support our work.

Tareq, thank you for that call to resist the exceptionalization of Gaza. I think that’s incredibly important. Indeed, Gaza seems to be defined by Hamas — certainly by the international policy world — but in reality, as you said, Hamas is a fig leaf that justifies the Israeli blockade and siege, and it enables the international community to justify what Israel is doing to Gaza.

And that brings me on to my next question, on reconciliation between the two main political parties, Fatah and Hamas. Now, as you mentioned, since the victory of Hamas in 2006 in the Palestinian Legislative Council elections — which really was a reaction to the untenable situation created by the Oslo regime — and the rejection of these elections by the international community and Fatah, which resulted in Israel laying siege to the Strip, there’s been this pretty impregnable divide between the two main parties. Over the many years since, there have been various attempts to reconcile them — attempts led by the international community and also internal pressure from Palestinian activists, namely in 2011. And this year we saw the PA once again engage in so-called “reconciliation talks,” but they broke down. And with the election of Biden to the White House, this seems no longer to be a priority, if indeed it ever was one.

Can you talk to us about the internal dynamics of reconciliation?

Tareq Baconi 18:20

I think there can be a lot of work done to explore, in each of these reconciliation efforts, what went wrong and why the parties were unable to convene. But I think the reason for that, and as I see it in my own writing, is that there’s a fundamental refusal by both parties to concede that there is, at a minimum, a plurality in how the Palestinian struggle should be waged. Each faction views its own ideology as the only ideology that is capable of liberating Palestine, and they view any kind of concession around that ideology as one that undermines not only the faction, but also the Palestinian struggle writ large.

So Hamas, for example, believes that the idea of negotiations from a position of weakness or negotiations without armed struggle is fundamentally defeatist, and therefore views any kind of concession to the PA — which is obviously dominated by Fatah — as something that would undermine the Palestinian struggle. And equally, Fatah — or the PA — would view any kind of resort to armed struggle, or even any kind of Islamist ideology, as something that would fundamentally marginalize the Palestinian struggle from the international community, and therefore something that should be avoided at all costs.

What this dynamic creates is a zero-sum game, where each faction begins to view the other faction as almost a bigger enemy than Israeli domination and control, because they view that that kind of concession would end up undermining the Palestinian struggle in all shapes and forms.

So I think that we’ve reached a situation where the factions now — each of the two factions, Hamas and Fatah — are actually more interested in maintaining their factional power over the Palestinian Authority and the institutions of governance under Israeli occupation, rather than in recreating institutions of liberation that can hold a plurality of Palestinian visions and a plurality of Palestinian ideologies that can all be harnessed in an effort to resist Israeli occupation.

So right now, unfortunately — and this is how we see the reality unfolding on the ground — the Palestinian institutions of liberation, embodied of course by the PLO, have become subsumed into the political structures of governance that the Oslo Accords have created, and that by design are meant to sustain and maintain Palestinian wellbeing under Israeli domination — so to sustain livelihood under unyielding Israeli control.

And I think both factions, both Hamas and Fatah, have in their own ways, in their own rhetoric, in their own ideologies, embraced that and accepted that political reality at the expense of reconciling around a broader vision that might hold different ideologies and allow for a more pluralistic, more representative, more inclusive form of Palestinian liberation.

Yara Hawari 21:47

And meanwhile, in this zero-sum game where they’re more interested in consolidating their power, they’re becoming increasingly authoritarian — both Fatah and Hamas — and a lot of Palestinians have been calling to clean house rather than focus all energies on holding onto the crumbs of international support that’s left.

What would you think about this?

Tareq Baconi 22:12

I think it’s absolutely essential that Palestinians clean up their house, in the sense that they stop playing by the rules of the game that are dictated by Israel and by its allies globally. I think Palestinian leadership has a responsibility to be, first and foremost, accountable to the people that they’re trying to lead into liberation.

And in that sense — I mean, I have a lot of thoughts around this term, “cleaning up the house” — but if I’m being kind in interpreting that call, it’s fundamentally to say that the Palestinian leadership needs to start being accountable to the Palestinian people, who are all calling for freedom, equality, and justice. Those are the demands that are coming up from the people, whether they’re under occupation or elsewhere. They’re calling for return, and they’re calling for the end of the ongoing colonization that began before the Nakba, and obviously that culminated in the Nakba in ’48.

The political institutions that lead the Palestinian struggle need to heed that call. So it’s no longer about dividing up ministries, or forming a Palestinian Authority that’s representative through elections, or about negotiating land swaps and the borders of partition in future negotiations. That’s not where the Palestinian people are at, that’s not what they’re calling for, and limiting the Palestinian struggle to those kinds of debates and those kinds of discussions is accepting, again, the terms of debate that have been imposed on Palestinians by Israel.

For the Palestinian struggle to be effective, I think it’s a prerequisite for the Palestinian leadership to shift the terms of debate and to start actually taking their mandate from the Palestinian people, who are calling for fundamentally different things, who are calling for a much broader vision of liberation and recreating institutions of power — whether it’s the PLO or other institutions — that are able to overcome the fragmentation that we’ve talked about in this episode and reunite the Palestinian people in a single vision of liberation. That’s what is the responsibility of the Palestinian leadership today, as I see it. And until that happens, until the Palestinians and the Palestinian leadership are able to overcome this divisiveness that’s imposed on them by the Israeli government and start declaring their own goals of liberation, defining a vision that can unite all the people in a single unit against Israeli settler colonialism — if that’s what we mean by “cleaning up the house,” then yes, I think that’s a prerequisite.

And I think it’s incumbent on the leadership to do this, especially at a time when the biggest power that we still have in our capacity as Palestinians is the people, and the fact that the people are still standing steadfast on the land and still resisting expulsion and dispossession. Given that even our closest allies in the region are beginning to normalize with Israel, the leadership really has no cards left other than to turn to the people and their popular allies globally. And I think that recrafting the liberation struggle to take that into account is an imperative.

Yara Hawari 25:43

Thank you, Tareq. I think normalization is a topic for another podcast, perhaps. But I think it really hammers home that many of these regimes, which have normalized with Israel — or rather, officialized their longstanding relations with the state of Israel — were never on the side of the Palestinian struggle or really ever cared about Palestinian liberation. And I think it’s very demonstrative in the way that they treat their own populations and political dissidents.

But all that you mentioned really is quite a formidable challenge, and I think it can be quite overwhelming. So in light of all of this, I was hoping that you could talk to us a bit about any kind of new or revived framings that we’re sort of seeing coming into the picture that might be useful to the Palestinian struggle for liberation.

Tareq Baconi 26:08

Absolutely. I think it’s absolutely overwhelming and formidable challenges. And I don’t say some of these things lightly. I speak to a lot of Palestinian leaders through my job who talk about the fear of giving up on political institutions like the Palestinian Authority, because those decisions for many might be existential — Palestinians take their livelihood from these institutions.

So that kind of reformulation — the breaking out of the stranglehold of the Oslo Accords and recreating institutions of liberation that are effective — are going to be met with incredible backlash from the Israelis, of course, but also from the international community that has a vested interest in maintaining the status quo and maintaining this facade of a peace process that does nothing other than sustain Israeli control over the Palestinian territory. So any kind of reformulation to the effect of what I’m talking about is fundamentally disruptive to the reality on the ground and is going to be met with extreme resistance.

At the same time, we are living in a world where we are seeing examples of what that kind of popular mobilization could yield. Obviously there are movements around the world — whether it’s Black Lives Matter or feminist movements or climate change’s Extinction Rebellion or whatever the case might be — that are forcing conversations, that are forcing systems of oppression to at least take stock of the reality of their oppression. I’m not naive or idealist in the sense that I don’t think that any of these movements have received the justice they deserve, but they have been capable of disrupting and of forcing at least the contours of conversations to begin changing.

And I think those movements hold a lot of inspiration for Palestinians, the same way that the ANC in South Africa or the civil rights movement in the US or anti-colonialism elsewhere are sources of inspiration for the Palestinian movement. The more contemporary manifestations of movements that are calling for justice and for dismantling structures of domination are also sources of inspiration for Palestinians, and there’s a lot for us to learn from.

And we actually don’t need to look far afield. We can turn to the revolutions that happened in the Arab world as an example of what mass mobilization can mean in terms of facing authoritarianism and dictatorship. And of course, listeners will be thinking, “Well, the Arab revolutions ended up actually in more authoritarianism and in more oppression.” And that’s true, and that’s the reality we’re living in. But the way I see it, at least, is that a barrier of fear was broken through those revolutions — that a barrier of believing that the sitting dictators will never be removed or will never be dismantled — and I think there’s no turning back from the recognition that the power of the street can actually lead to that change.

And just like I believe the Arab revolutions are ongoing, I think the Palestinian struggle is also ongoing, in the sense that its understanding now — in this 21st-century reality we’re living in — that there are new forms of mobilization that can reshape an alternative phase of Palestinian liberation that is rooted in the power of the people.

And to take the conversation back to Gaza, the Great March of Return, for me, is the biggest example of that. Even though, again, it wasn’t met with real change and it was met with immense loss of life because of Israel’s use of live fire against unarmed civilians. But that was an example, for me, of what the future holds in terms of Palestinian mobilization. And this builds on a whole history of mobilization, from the intifadas in the 1920s onwards. But I think an expansion of that — an expansion of alliances with global movements and more strategic direction of these popular mobilizations — is in our future.

Yara Hawari 31:10

Tareq, that’s a brilliant point to end on. The time really just flew by. I could continue talking and chatting to you forever, but I’m afraid we don’t have time and we’re going to have to stop there. So thank you so much for joining me for this episode of Rethinking Palestine.

Tareq Baconi 31:27

Thank you for having me. It’s great.

Yara Hawari 31:33

Thank you for listening to Rethinking Palestine. Don’t forget to subscribe and leave us a review. For more policy analysis and to donate to support our work, please visit our website, al-shabaka.org. You can also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Tareq Baconi serves as the president of the board of Al-Shabaka. He was Al-Shabaka’s US Policy Fellow from 2016 – 2017. Tareq is the former senior analyst for Israel/Palestine and Economics of Conflict at the International Crisis Group, based in Ramallah, and the author of Hamas Contained: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance (Stanford University Press, 2018). Tareq’s writing has appeared in the London Review of Books, the New York Review of Books, the Washington Post, among others, and he is a frequent commentator in regional and international media. He is the book review editor for the Journal of Palestine Studies.

Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network is an independent, non-partisan, and non-profit organization whose mission is to convene a multidisciplinary, global network of Palestinian analysts to produce critical policy analysis and collectively imagine a new policymaking paradigm for Palestine and Palestinians worldwide.