Overview

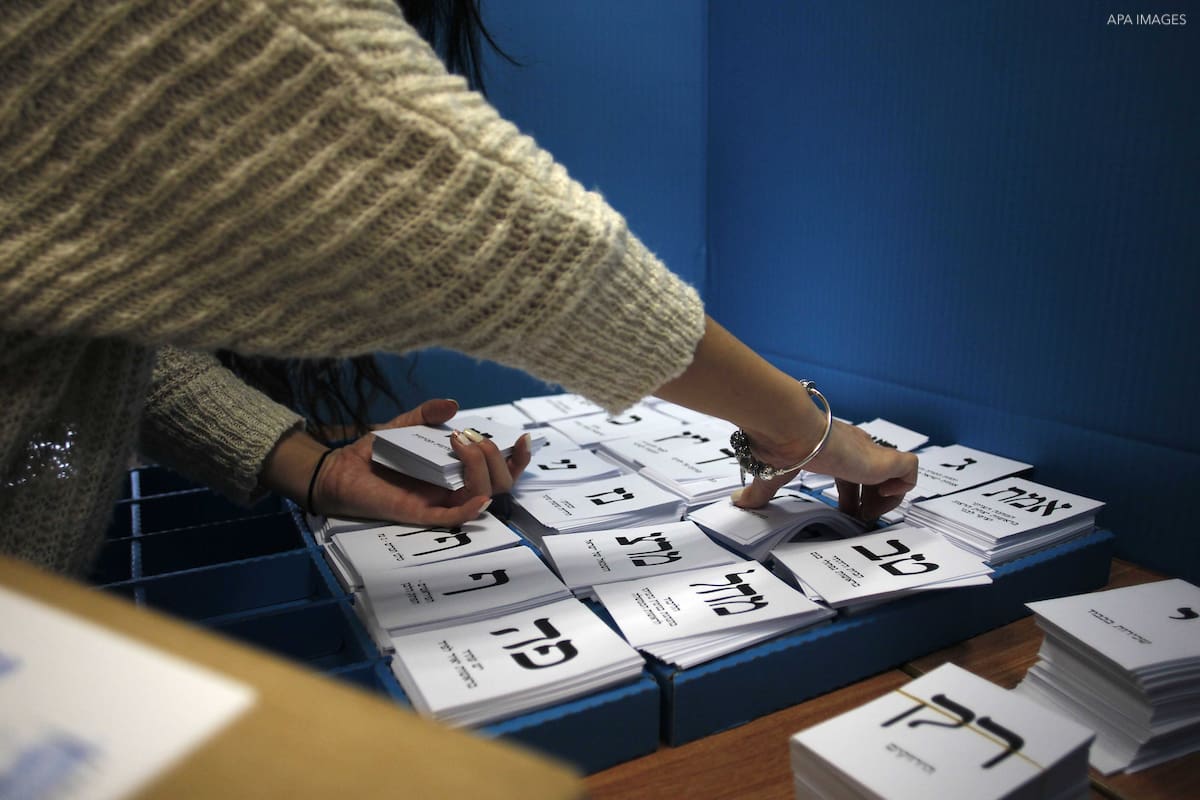

Palestinian citizens of Israel earlier this year organized a campaign to boycott the April Knesset elections. Under the banner of the “Popular Campaign for the Boycott of the Zionist Elections,” the campaign called on Palestinians to refuse participation in the Israeli general elections so as not to recognize the Knesset as a legitimate entity.

As a result – and also due to disillusionment with the Arab Joint List, which had split from four united parties into two competing pairings – Palestinian voter turnout dropped below 50 percent. (Such turnout had been, for instance, 63 percent in 2015). In the run-up to the September 17 elections, the Joint List has again fused, with the hope for a larger Palestinian turnout. Whether the move succeeds remains to be seen, but for those who advocate for a boycott of the elections, the status of the Joint List has little bearing on the argument for non-participation.

On the occasion of the imminent elections, Al-Shabaka is recirculating this roundtable debate, first published in April 2019, in which Al-Shabaka Policy Analyst Nijmeh Ali and Al-Shabaka Palestine Policy Fellow Yara Hawari argue against and for boycotting Knesset elections, respectively.

What do Palestinian citizens of Israel gain by participating in the Israeli elections? By boycotting them?

Nijmeh Ali: Participating in the elections allows Palestinians to organize themselves internally, conduct political debates, and lobby for their civic and national rights in Israel and beyond. Participation should not be viewed as a position of principle, but rather as a tactic to use until opportunities arise to adopt more far-reaching strategies. Essentially, Palestinians must ensure that suitable political ground is created, as the act of rejection without constructing a solid alternative establishes a political passivity that is dangerous for a colonized, occupied, and oppressed people.

For instance, boycotting the elections could result in the dwindling of the Arab parties, which would lead to a leadership vacuum. Despite criticism and frustrations, parties still operate as the main organizing mechanism for political, social, civil, and national issues. Weakened parties would likely lead to the strengthening of familial and sectarian communities and their political organizing mechanisms, such as the hamula (clan) and mukhtars (elders). These mechanisms have historically been vulnerable to co-optation by the Israeli regime and encourage fragmentation.

The leadership vacuum could also be filled by Palestinians who operate within Zionist parties. These figures, who have been active since 1948, polish Israel’s democratic image without presenting challenges to it. With the state’s support they would be poised to take on more prominence: 16.8% of Palestinians already voted for Zionist parties in the last elections – the lowest percentage since 1948.

Electoral rejection without constructing a solid alternative establishes a political passivity that is dangerous for a colonized, occupied, and oppressed people Share on XThe elections are therefore not simply an electoral battle, but one over Palestinian representation more broadly. With the strengthening of familial and sectarian mechanisms and the “Arab Zionist” model of leadership likely results of a successful boycott, it is more important than ever for Palestinians to maintain electoral participation.

Yara Hawari: Far from being a sign of apathy, election boycotts are a political tool used to convey an electorate’s dissatisfaction and disaffection. Indeed, other colonized, oppressed, or marginalized groups have used abstention or casting blank ballots as an expression of rejection. For instance, Sinn Fein – the largest republican party in Northern Ireland – takes part in the British elections but refuses to sit in the British House of Commons or vote on any bills in rejection of the centuries-old British claim of sovereignty over Northern Ireland. Black South Africans fighting for liberation from colonial apartheid also did not seek inclusion within the system, but rather sought to dismantle it and create a new, just, and fair one. In this way, they directed their energies toward a political alternative rather than “patching up” a broken system.

Boycotting the Israeli Knesset elections follows a similar ideological stance in that it refuses the legitimacy of the colonial political institution. It explains that the elections serve to bolster the image of Israel as a democracy, while in fact at least 65 laws indirectly or directly discriminate against and target Palestinians in all areas of life, including the Nakba Law, which allows the Israeli finance minister to reduce or withdraw funding from any institution that marks Israeli Independence Day as a day of mourning. Moreover, Israeli electoral law does not allow for the participation of those that question the Jewish character of the state of Israel, meaning that Knesset members cannot challenge Israel’s definition of being both Jewish and democratic.

How does the historical context of Palestinian political participation inform your stance?

Nijmeh Ali: Historically, Palestinian citizens of Israel have been willing to participate in the political process, even in moments of tension and alienation. From 1949 to 1973, average voter turnout among Palestinians in Israel was 86%, though this was mainly due to the military rule imposed on them between 1948 and 1966. The dominant Israeli Labor Party, Mapai, maintained its hegemony for 30 years and controlled the Palestinian vote by creating affiliated Arab lists headed by co-opted leaders who would guarantee the party virtually all Palestinian votes.

After the end of military rule and the events of Land Day (March 30, 1976), Palestinians’ political awareness increased, and the average voter turnout remained high at 72%. While voter turnout declined during the 1990s and after the Second Intifada, it rose again in 2015 with the creation of the Joint Arab list. Turnout in those elections rose to 64%, with the vast majority (82%) casting their ballots for the list. This history signals Palestinians’ embrace of the political process, which should be capitalized on rather than stifled.

Further, the government of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was able to move the peace process forward in the 1990s because of Arab parties, which had five seats in the Knesset and helped maintain Rabin’s small coalition of 58 seats, which needed the minimum of 61 to pass any law. This example demonstrates how Palestinian citizens of Israel can use political power effectively when the circumstances allow it – either by bolstering or blocking a coalition’s influence.

The massive efforts of the right wing to marginalize the Palestinians aims to prevent them from practicing this power. This was clear in 2014 when the Knesset voted to increase the electoral threshold to 3.25%, with the aim of excluding small parties from the Knesset. The Arabs’ response was the formation of the Arab Joint list, which was comprised of four small parties. Legal actions also continue to marginalize Arab parties, including attempts to ban political lists and candidates from election participation.1

Yara Hawari: The Palestinian citizens of Israel have always been a politically active community. In the 1950s and 1960s, voter turnout reached as high as 90%, with the aim of making as many political gains as possible in the hope that full and equal citizenship could be achieved. In the 1990s the Abnaa al Balad movement began organizing calls to boycott the Knesset elections in response to Israel’s military attacks in southern Lebanon.2 The 2001 prime minister election saw Palestinian voter turnout plunge to only 18%, and of those, a third cast blank ballots. This was in response to the events of October 2000, when Israeli soldiers gunned down 13 Palestinians in the streets, 12 of whom were Israeli citizens, who were protesting in solidarity with demonstrators in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Far from being a sign of apathy, election boycotts are a well-used political tool Share on XYet history also shows that regardless of electoral participation the Palestinian citizens of Israel have not made any significant gains within the Israeli political system. This is particularly demonstrated through land and space, as no new Arab towns or villages have been built since 1948, and building permits are frequently denied. In contrast, the Israeli government is constantly building new Jewish-only neighborhoods and settlements. This has resulted in overcrowding of Palestinian Arab areas, with many Palestinians resorting to building without “permission.” Palestinian Arabs are also not permitted to buy property in most of the country and are even prevented from residing in certain communities by admissions committees that can deem their ethnicity or religion “unsuitable.” And while some Palestinians have achieved senior positions in Israeli institutions, including a judge on the Supreme Court and an ambassador, their cases are exceptions that prove the rule. Thus, the Israeli system does not allow for non-Jewish equity. As a result its glass ceiling cannot be broken within the current political framework.

How do recent events such as the passing of the nation-state law and the dissolution of the Arab Joint List come into play?

Nijmeh Ali: The nation-state law embedded Jewish supremacy and Palestinian inferiority by defining Israel as a state for Jews only. It does this through privileging Jewish citizens over non-Jewish citizens legally, symbolically, and politically – turning the reality of segregated life into an official apartheid state. It also reflects the political reality in Israel, which has seen the rise of the right and the inability of the Arab Joint List to counter this rise alone. It is crucial to reconsider broad coalitions and to push for structural change in Israeli politics.

However, the Joint List did succeed in creating public awareness of the implications of the law as well as a significant political debate. Thousands of Palestinians and progressive Jewish citizens took to the streets in Tel Aviv to protest the law, led by various Palestinian political leaders. Apartheid terminology is now consistently deployed in Israeli political debates at an institutional level. Though the dissolution of the Joint List was disappointing it was not surprising because the list was constructed mainly for electoral reasons. The most obvious implications of its demise will be the likely loss of voters and Knesset seats. After the election, if both Arab lists (Hadash-Ta’al and Balad-United Arab List) pass the threshold, they are likely to work together as they did during the multi-parties era.

Palestinian citizens of Israel can act when circumstances guarantee mass support politically and on the ground Share on XYara Hawari: The passing of the nation-state law in 2018 and comments by Netanyahu affirm that Israel is a state for Jews alone. Unlike the international community, many Palestinians were not shocked by the law or Netanyahu’s comments, as they simply confirmed what is already in place in order to appease the growing Israeli right. However, the law and the commentary about it did highlight more than ever that Palestinians will never be considered equal citizens of the state, particularly while Israel’s separation between citizenship and nationality allows for discrimination against non-Jews.

The nation-state law also highlighted a failure of the political representation of the Palestinian community inside Israel. The Arab Joint List failed to muster a strong response. Several of the Palestinian Knesset members boycotted the parliament for a short period, and others led the rally against the law in Tel Aviv, but they did not present a collective strategy. They could have, for example, collectively refused to sit in the Knesset but continued to run in the elections to maintain their electoral mandate (similar to Sinn Fein, as discussed above). Earlier this year the Joint List dissolved, a reflection of an internal struggle of egos within the various parties. In this context, it is clearer than ever that Palestinians must pursue political mobilization outside the Israeli system.

What role does voting or boycotting have in the continuous and future struggle for Palestinian liberation?

Nijmeh Ali: Participation in the elections is a double-edged sword. Israel uses its Palestinian presence to prove that it is a democracy, at least rhetorically. However, what really threatens Israel is a Palestinian who is a producer at all levels, who is economically independent and pays the bills every month without relying on Israeli national insurance. This is the model that can break the hierarchical relationship between master and slave and rearrange the boundaries of the political game. The greater the strength and influence of the Palestinians in Israel – through their presence as consumers, taxpayers, and a core component of the labor force – the greater the impact of their protests in the future (and the more racism they will be targeted with). Thus change that can bolster the Palestinian citizens of Israel should involve establishing an internal financial support system related to a strategic plan of protest.

Maintaining political parties and engagement in the political system, such as voting, should also be a priority, at least in the short to medium term. It would be risky to demand a change in the political mechanism today. Leaving the Knesset cannot be done without planning. In the context of an exhausted society that lacks confidence in its leadership, a strategic political plan, and regional and international support, change must be considered carefully.

Palestinian citizens of Israel must set aside the romantic notion of sumud (steadfastness) in order to politicize and mobilize their masses, establishing links between daily needs and national demands, between the private and the public, and between the civil and the political.

With economic and political mechanisms in place, Palestinians can act when circumstances guarantee mass support politically and on the ground. Otherwise, Palestinians will fall into a trap of political passivity and chaos.

Yara Hawari: Recent political maneuvers in Israel do not reveal anything new; rather, they reaffirm the state’s position, which sees Palestinians as a fifth column to be tolerated only if they remain segregated, ghettoized, and passive. It has never been timelier for Palestinian citizens to reject this structure and to demand that their political leadership do so as well.

Boycotting the Knesset elections must be a tactic that is part of an overall vision for the Palestinian citizens of Israel Share on XYet boycotting the Knesset elections does not, on its own, qualify as a strategy. Rather, it must be a tactic that is part of an overall vision for the Palestinian citizens of Israel. Those wanting to help create a new Palestinian political strategy must harness the momentum gained from boycotting to develop alternative political spaces outside of Israeli institutional politics. One practical way to do this is for people to organize meetings on the day of the elections to discuss the revival of a collective strategy and the steps needed to implement it. All of this, however, must also be done in the larger political context of the Palestinian people and their fragmented communities.

The Palestinian citizens of Israel must reaffirm their place in the Palestinian project for sovereignty, asserting that they are part of the struggle and not simply an internal Israeli affair. Their intimate experience with Israel places them in a strong position to take a leading role in discussions about new political models and leadership structures. In this way, they could radically contribute to changing the discourse on who and what is Palestine, paving the way for Palestinians across all geographies to unite and demand the fulfillment of their quest for self-determination and human rights.

- The Central Elections Committee disqualified the Arab joint slate Balad-United Arab List and Ofer Cassif, a member of political alliance Hadash-Ta’al, from running in the April 2019 elections. The decision was referred to the Supreme Court for approval. On March 17, 2019, the Supreme Court reversed the Central Elections Committee decision.

- Abnaa al Balad is a Palestinian political movement established by university students in the 1970s. The movement called for the end of the occupation of the 1967 territories, the return of Palestine’s refugees, and the establishment of one secular and democratic entity in historic Palestine that would not be based on ethno-religious rights. Ideologically, Abnaa al Balad is close to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.

Yara Hawari is Al-Shabaka’s co-director. She previously served as the Palestine policy fellow and senior analyst. Yara completed her PhD in Middle East Politics at the University of Exeter, where she taught various undergraduate courses and continues to be an honorary research fellow. In addition to her academic work, which focused on indigenous studies and oral history, she is a frequent political commentator writing for various media outlets including The Guardian, Foreign Policy, and Al Jazeera English.

Dr. Nijmeh Ali is a Fellow at the National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies (NCPCS), University of Otago and a lecturer in the GDCR program at Otago Polytechnic. Her research focuses on resistance and activism within oppressed groups, particularly among Palestinian activists in Israel. Her research provides a critical perspective on studying resistance and revolution in non-western societies and challenges the classic liberal framework of citizenship. It also deals with exposing strategies used by oppressed and marginalized groups in resisting their subjugation; therefore, it applies to women, minorities, refugees, and migrants.