Introduction

Lebanese officials have revived calls to disarm Palestinian factions inside refugee camps, presenting it as part of efforts to curb “illicit weapons” and reinforce state sovereignty. Yet for many Palestinians and regional observers, the refugee-camp disarmament initiative signifies an attempt to recalibrate the region’s security landscape. It also revives traumatic collective memories of earlier disarmament campaigns that left camps exposed to massacres.

The renewed call for disarmament unfolds amid overlapping local and regional dynamics that inform the policy: domestic political deadlock and external pressure to quell resistance and contain Hezbollah and other armed actors amid continuing Israeli assaults and the occupation of the Shebaa Farms and Ghajar in southern Lebanon. For many observers, it echoes recent attempts by the Palestinian Authority (PA) to reassert control over Jenin, one of the West Bank’s refugee camps, under the banner of “law and order”—a move that ultimately left the camp vulnerable to Israeli assault.

Against this backdrop, Jaber Suleiman and Wesam Sabaaneh explore what is new about the current disarmament push, what it reveals about Lebanon’s governance of Palestinian refugee camps in the country, and how a rights-based approach could chart a safer future for all. Together, they demonstrate how the refugee question remains at the heart of the Palestinian struggle, arguing for re-centering legal rights as the only durable path toward stability in Lebanon and the wider region.

The interview below is an edited version of a longer conversation held in August 2025 through our Policy Lab program. The discussion, available in Arabic, may be viewed in full here.

How does the disarmament policy fit within the legal and institutional frameworks governing Palestinian life in Lebanon?

Jaber Suleiman

To understand the debate over weapons in the camps, we must first situate it in the broader legal and institutional context that has governed Palestinian refugees for decades. Lebanon has no specific legislation for Palestinian refugees. Legally, the Lebanese state treats us as foreigners, and at times as a special category of foreigners who are denied rights that even other non-citizens enjoy. Palestinians cannot own property, face restrictions in dozens of professions, and are barred from social security benefits.

This creates what I have long described as institutionalized discrimination: a web of legal, administrative, and social exclusions that entrench and reproduce the marginalization of Palestinian refugees. The General Directorate for Palestinian Refugee Affairs, established in 1959, functions essentially as a civil registry, limited to recording births and deaths and issuing identity cards. It was initially created during the Shihabist era (1958–70), extending from President Fouad Shihab’s tenure into that of his successor—a period marked by the tightening of security control over the Palestinian camps by Lebanese military intelligence.

In 2005, following the withdrawal of Syrian forces, the Lebanese government established the Lebanese-Palestinian Dialogue Committee (LPDC), which operates under the authority of the prime minister. It is an advisory body with no executive powers. Although its primary mandate includes addressing social, economic, legal, and security issues in the camps—among them the management of arms both inside and outside the camps—the security perspective has dominated its work, especially in the current period. This reflects Lebanon’s broader policy orientation: treating the Palestinian presence primarily as a security threat rather than a rights issue.

Palestinian refugees in Lebanon have long endured various forms of discrimination, including spatial marginalization. The Lebanese state treats refugee camps as zones of insecurity and criminality, surrounding them with military checkpoints and restricting the movement of their inhabitants. Unless this framework is fundamentally reformed, any attempt at disarmament will only deepen exclusion rather than strengthen the rule of law.

Wesam Sabaaneh

Indeed, the relationship between the Lebanese state and Palestinian refugee camps is defined by a security logic rather than social responsibility. In Lebanon, the agency responsible for dealing with Palestinian refugees reports to the Ministry of Interior, whereas in Syria, it falls under the Ministry of Social Affairs. That distinction is telling of how the Lebanese state views the camps as potential threats, not communities with rights.

As a result, camps are surrounded by checkpoints, and residents require permits even to bring in construction materials. This state of siege isolates refugees physically and psychologically. It also leaves the camps without adequate law enforcement. The Lebanese army does not enter the camps, and the police have no jurisdiction, so internal security falls to popular committees and factions.

The danger is that disarmament becomes a slogan masking Lebanon’s refusal to address Palestinian refugees’ civil and economic rights Share on XThe Cairo Agreement of 1969—signed in Egypt between the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Lebanese army under former President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s auspices—formally acknowledged Palestinians’ right to bear arms in the liberation struggle and granted them limited self-administration inside the refugee camps. When the agreement was annulled in 1987, no alternative framework was established to replace it. The result is that the camps are blamed for a lack of security, yet Palestinians are denied the legal tools to maintain order.

Moreover, one must ask what kinds of weapons could realistically exist within a besieged refugee camp today. Given the intense securitization and external control surrounding these camps, the weapons found there are more likely to be small arms, not heavy weaponry.

The debate should not be about disarmament but about enforcing security through legitimate, accountable structures that include the community. The danger is that disarmament becomes a slogan masking Lebanon’s refusal to address refugees’ civil and economic rights. Without those rights, no amount of disarmament will bring about stability.

How are Palestinian actors navigating disarmament within Lebanon’s broader efforts to reassert state sovereignty?

Wesam Sabaaneh

The internal Palestinian divide between the mainstream PLO factions, led by Fatah, and the resistance movements, such as Hamas and Islamic Jihad, continues to shape life within Lebanon’s camps. In September 2023, the Battle of Ain al-Hilweh, marked by fierce intra-Palestinian clashes that devastated parts of the camp, left the community deeply traumatized. In May 2025, President Mahmoud Abbas visited Lebanon in what was framed as a step toward “reasserting order,” publicly pledging to support efforts to disarm armed groups in the camps.

However, this announcement was made without consultation with local leaders, popular committees, or civil society. Many Palestinians in Lebanon saw it as an imposed agenda meant to appease Lebanese and international partners. Even within Fatah, there was resistance: local commanders feared being scapegoated if violence were to recur.

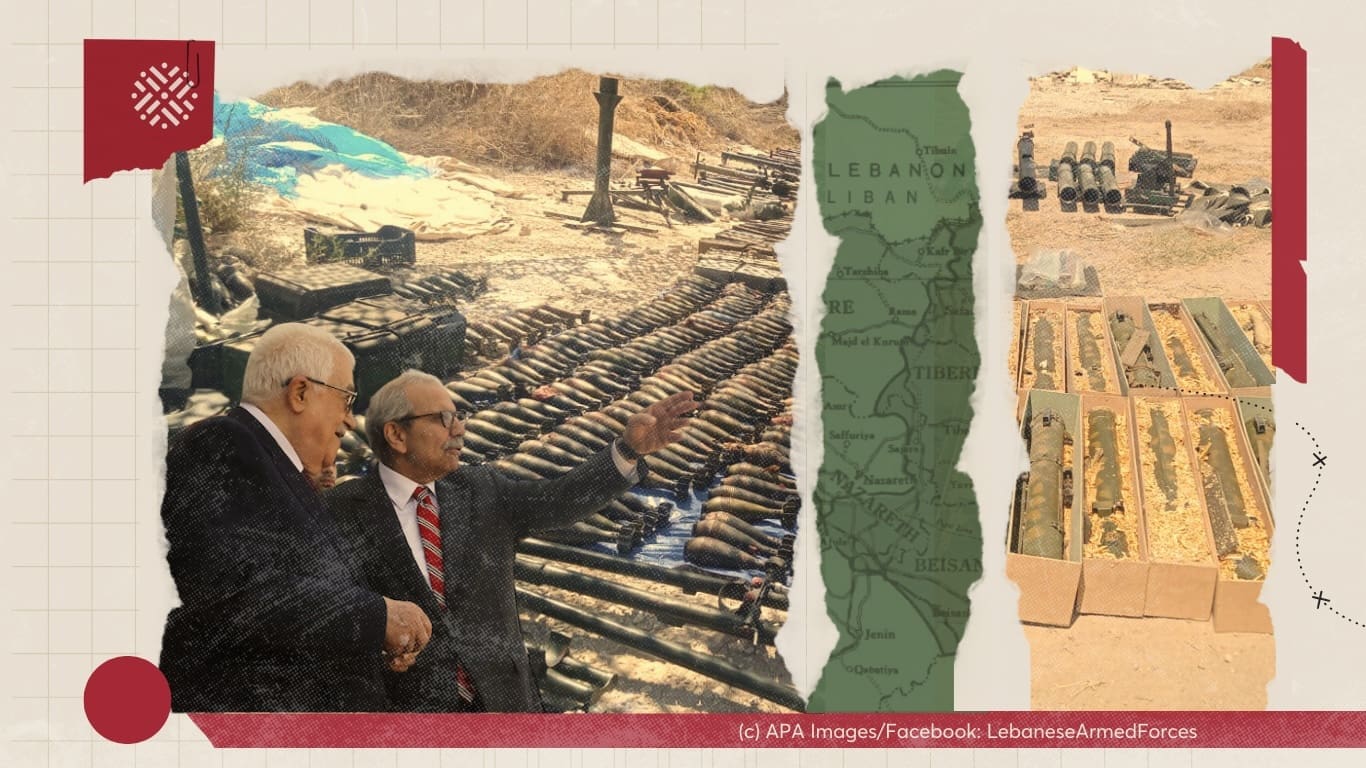

In August 2025, following Abbas’s visit, members of Fatah in the Burj al-Barajneh refugee camp handed over a small quantity of weapons to the Lebanese authorities. This handover was not a collective disarmament but the surrender of a few confiscated rifles by Fatah members. Nevertheless, it was presented as the beginning of a national process. In reality, it was political theater rather than a genuine plan.

For people in the camps, the core demand remains rights before disarmament—the right to work, to own property, to live without checkpoints. You cannot ask a community to surrender its only means of self-protection while denying it every form of security.

Jaber Suleiman

Stability cannot be achieved through coercion, and real sovereignty—Lebanese or Palestinian—must rest on law and equality, not on suppressing vulnerable groups. Palestinian refugees have been in Lebanon for more than seven decades. Denying them rights has not achieved security; it has deepened their everyday struggles and amplified their alienation.

Lebanon’s policy towards Palestinian refugee camps has oscillated between repression, abandonment, and slight openness. In the 1950s, there was cautious accommodation; in the 1960s, heavy surveillance; in the 1970s, limited autonomy under the Cairo Agreement; and after 1982, brutal repression culminating in the Sabra and Shatila massacre. Each phase left more profound mistrust between the state and the refugee community.

After the 1989 Taif Agreement, which shaped Lebanon’s post-war order, Palestinians were excluded from Lebanese national reconciliation, and a policy of neglect took hold. The creation of the LPDC in 2005—along with modest shifts in Lebanese discourse and pressure from international donors for a more rational rights-based approach to handling refugee affairs—did not, however, bring about meaningful change on the ground.

When officials today speak of disarmament, they draw on a long tradition of treating Palestinian refugees as a domestic security liability rather than a population entitled to international protection Share on XWhen officials today speak of disarmament, they draw on a long tradition of treating refugees as a domestic security liability rather than a population entitled to international protection. This logic persists even though Lebanon’s constitution already incorporates international human rights covenants that, if applied, would guarantee refugees the right to work, to education, and to a dignified life.

Ultimately, there is no dispute over the Lebanese state’s sovereignty across all its territory, including the Palestinian camps. The real test of state sovereignty is its ability to apply the law fairly, not in disarming powerless refugees while leaving systemic discrimination intact.

How are regional dynamics driving the disarmament agenda and influencing conditions for Palestinian refugees and prospects for the right of return?

Wesam Sabaaneh

Palestinian refugee camps have historically constituted environments conducive to resistance across geographies. They also serve as custodians of the right of return and stand as enduring symbols of Palestinian displacement. Palestinian refugees remain firmly committed to their legitimate right to resist occupation and to uphold their fundamental rights, foremost among them the right of return—particularly in Lebanon, given the challenging circumstances surrounding camp living.

For people in the camps, the core demand remains rights before disarmament—the right to work, to own property, to live without checkpoints Share on XFollowing the fall of the Assad regime and the subsequent decline of the so-called Axis of Resistance, the camps in Lebanon and Syria have come to represent significant obstacles for states seeking normalization with Israel. Consequently, the US administration has endorsed the disarmament of these camps as a step toward a broader colonial project aimed at erasing the Palestinian presence from the region as a whole.

Jaber Suleiman

Indeed, the current regional landscape—marked by the accelerating normalization with the Israeli regime, plans for “economic corridors,” and talk of a “post-conflict Middle East”—seeks to liquidate the refugee question rather than resolve it. Disarming refugee camps serves this agenda by stripping them of their identity as sites of political struggle and of their symbolic role as the last tangible embodiment of the right of return.

Steps toward disarmament are not new, but the regional dynamics have changed. In 1991, Palestinian factions handed over heavy weapons from within the camps to the Lebanese authorities in an effort to reach some form of agreement on the refugee question. Consequently, the Lebanese army was deployed around the refugee camps in the south. However, the state subsequently stalled any meaningful progress toward addressing the broader issues facing Palestinian refugees.

What’s distinctive now is the regional context. Lebanon is under pressure to consolidate border control and align with Western and Gulf agendas that seek to weaken armed resistance groups, including both Hezbollah and Palestinian factions. Beneath the pretext of reinforcing “Lebanese sovereignty” lies a broader US-Israeli strategy to reshape the region in the aftermath of October 7, 2023—one aimed at pacifying resistance movements and advancing the normalization agenda even further. Within this framework, it becomes easier for the Lebanese state to target the disarmament of Palestinian camps rather than confront Hezbollah, thereby aligning itself with US objectives and signaling compliance with international expectations.

The real test of state sovereignty is its ability to apply the law fairly, not in disarming powerless refugees while leaving systemic discrimination intact Share on XWhen we saw officials collecting weapons from Burj al-Barajneh camp on camera, it was clearly a performative gesture as mentioned earlier—a way for Beirut to show Washington and Paris that the state is “active.” The policy takeaway here is that Lebanese authorities are using the Palestinian file as a proxy battlefield for external agendas. This instrumentalization of refugees endangers Palestinians and threatens Lebanon’s fragile pluralism.

Palestinian and Lebanese civil society groups must resist this, while reaffirming a rights-based framework to tackling the Palestinian refugee question. Lebanon cannot build sovereignty on the exclusion of a community that has lived on its soil for seventy-five years. The only sustainable path is to bridge the gap between domestic law and international refugee norms, ensuring equality before the law. Any discussion of disarmament must be grounded in a comprehensive rights framework that centers on human security; otherwise, it risks reproducing insecurity.